1. I. Introduction

ongestive heart failure (CHF) is a complex clinical syndrome that can result from any functional or structural cardiac disorder that impairs the ventricle's ability to fill with or eject blood (1) . The treatment and prevention of HF has become a burgeoning public health problem reaching epidemic levels.

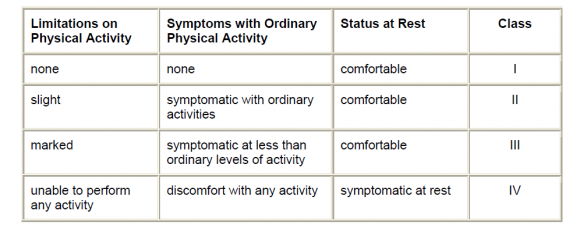

Especially for the elderly population (2) .Because of the high mortality rate associated with CHF, it is important to identify modifiable risk factors and develop effective strategies for the prevention of CHF in the general population. Results of prospective cohort studies have indicated that old age, male sex, hypertension, diabetes, obesity, valvular heart disease, and CHD are important risk factors for CHF (3) . There are only a limited number of ways in which the function of the heart can be affected. The most common causes of functional deterioration of the heart are damage or loss of heart muscle, acute or chronic is chaemia, increased vascular resistance with hypertension, or the development of a tachyarrhythmia such asatrial fibrillation (4) . In heart failure, the cardiac reserve is largely maintained through compensatory or adaptive mechanisms such as the Frank-Starling mechanism; activation of neurohumoral influences such as the sympathetic nervous system, the renin-angiotensinaldosterone mechanism, natriuretic peptides, and locally produced vasoactive substances; and myocardial hypertrophy and remodeling (5) . Persistent inflammation, involving increased levels of inflammatory cytokines, seems to play a pathogenic role in chronic heart failure (HF) by influencing heart contractility, inducing hypertrophy and promoting apoptosis, contributing to myocardial remodeling (6) . An increasing body of evidence suggests that oxidative stress is involved in the pathogenesis of a wide range of cardiovascular diseases, including hypertension, Type II diabetes, hypercholesterolaemia, atherosclerosis andheart failure (7) . Diastolic heart failure (DHF) and systolic heart failure (SHF) are 2 clinical subsets of the syndrome of heart failure that are most frequently encountered in clinical practice (8) . The New York Heart Association (NYHA) developed a functional classification for patients with heart disease (9) table (1.1).Heart failure is a clinical syndrome that may be difficult for a primary care physician to diagnose accurately, particularly if the symptoms develop slowly and are not so severe as to warrant immediate hospitalization (10) . Fatigue, dyspnoea and peripheral oedema are typical symptoms and signs of heart failure, but not necessarily specific (11) . Echocardiography is vital in evaluating patients with known or suspected HF (12) . A large number of high quality trials on pharmacological therapy have been undertaken in patients with left ventricular systolic dysfunction with all stages of disease from asymptomatic left ventricular systolic dysfunction to severe heart failure. The aims of treatment are to prevent progression of the disease, thereby reducing symptoms, hospital admissions and mortality (13) . The beneficial role of statins in HF may be explained by its anti-inflammatory effects (14) . According to the cytokine hypothesis, HF progresses because cytokines exacerbate haemodynamicabnormalitie or exert direct toxic effects on the heart (15) . Cardiomyocyte loss by apoptosis has been recognized as a potential cause of heart failure .The prevention of cardiomyocyte apoptosis may be a part of the protective mechanisms of statins against heart failure (16) .

2. II. Subjects & Methods

3. a) Patients

This study was carried out at Al-Sadr medical city in Al-Najaf governorate from November 2011 until August 2012. Sixty male patients completed the course of atorvastatin for three months successfully. All patients were previously diagnosed with systolic heart failure and receiving the traditional anti failure treatment. Some of those patients (group one and group two) have normal lipid profile, while patients in group three have dyslipidemia. All patients did not receive any lipid lowering treatment (statin). Their age ranged from (35-72)

4. b) Healthy Subjects

Twenty subjects who were apparently healthy selected for the purpose of comparison. These subjects were selected from the medical staff and some relative volunteers. All of them were males. Their ages ranged from (-) years.

5. c) Exclusion Criteria

? Dyslipidemia (group one and group two).

? Previous statin treatment.

? Diabetes mellitus.

? Ischemic heart disease.

? Female.

6. d) Sample Collection And Preparation

A blood sample (10) was collected by vene puncture used a sterile disposable syringe in a plane plastic tube from each of the healthy subjects and patient after fasting overnight , and left at room temperature for 30 minutes for clotting , then centrifuged at 3000 rpm for 10 minutes.

Serum was taken by micropipette and divided into 2 parts: lipid profile.

2. The second part was subdivided into 4 parts and stored at (-20C)to be used in other tests (hs-CRP, TNF-?, total antioxidant status and adiponectin).

7. e) Statistical Analysis

All data were expressed as mean ± standard error means (SEM). Statistical analyses were carried out using paired t-test, independent t-test and one way annovato compare between mean values of parameters. P value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. Descriptive analysis was carried out by SPSS16 software.

8. III. Results

a) The effect of atorvastatin on lipid profile parameters (TC, TG, HDL-C, LDL-C, VLDL-C) in patients with heart failure i. Group one Table 2. shows the lipid profile parameters of group one patients who have heart failure with normal lipid profile, they did not receive atorvastatin therapy. Comparison is also made with control group.

In regard to total cholesterol (TC), the table showed that there is significant difference between the pretreatment value of heart failure patients and healthy individuals. However , the pretreatment value is within the normal range in the literature.

The other lipid profile parameters values of this group (TG, HDL-C, LDL-C, VLDL-C) also are significantly different from the control group.

Within the group, comparison is made among the three visits during the three months follow up duration (pretreatment, one half month, three months).

This table showed that the first visit values of TC and HDL-C are not significantly changed from the pretreatment values, while they are significantly different for TG, LDL-C and VLDL-C.

All lipid profile parameters (TC, TG, HDL-C, LDL-C and VLDL-C) readings after three months did not significantly changed from the previous values.

ii. Group two Table 3. showed a comparison between pretreatment values of all lipid profile parameters (TC, TG, HDL-C, LDL-C and VLDL-C) in group two patients, who complain from heart failure with normal lipid and receiving atorvastatin therapy, and control group.

This table shows a significant difference in all lipid profile parameters (TC, TG, HDL-C, LDL-C and VLDL-C) between pretreatment values of grouptwo and healthy individuals in control group. Another comparison is made between the three visits during the follow up duration for this group.

1. The first part was send to the hospital laboratory for After one-half month follow up, all lipid profile parameters (TC, TG, HDL-C, LDL-C and VLDL-C) are significantly different from pretreatment values.

After three months treatment with atorvastatin, the results showed further significant lowering of all lipid profile parameters (TC, TG, HDL-C, LDL-C and VLDL-C) from the previous follow up visit.

iii. Group three Table 4. includes a comparison of lipid profile parameters (TC, TG, HDL-C, LDL-C and VLDL-C) between pretreatment values of group three patients who complain from heart failure and dyslipidemia, they received atorvastatin treatment.

The results showed that all lipid profile parameters are significantly different between retreatment values of this group and healthy individuals in control group. All lipid profile parameters in group three patients are significantly changed after one-half month treatment with atorvastatin.

At the end of follow up duration, the lipid profile parameters are significantly changed as compared with mid-duration values. b) Serum level of hs-CRP, TNF-?, adiponectin and total antioxidant status and ejection fraction of group one (patients with heart failure and normal lipid profile not treated with atorvastatin), group two (patients with heart failure and normal lipid profile treated with atorvastatin), group three (patients with heart failure and dyslipidemia treated with atorvastatin) and control group.

Table 5. showed a comparison between pretreatment values of all biomarkers and ejection fraction with healthy individuals in control group. The pretreatment values of hs-CRP, TNF-?, adiponectin and total antioxidant status are significantly different from control group.

There is a significant difference in pretreatment value of hs-CRP and TNF-? between group one and group three.

For adiponectin, there is a significant difference in pretreatment values between group one and group two, also a significant difference is shown between group two and group three.

Regarding to ejection fraction, the pretreatment value of each group is significantly different from control group patients.

c) The effect of atorvastatin on the serum level of hs-CRP in patients with heart failure Table 6. showed that there is no significant change in serum level of hs-CRP in group one patients who have heart failure and normal lipid profile and not receiving atorvastatin therapy neither after one-half month nor after three months.

While in group two patients who have heart failure and normal lipid profile and receiving atorvastatin therapy, there is a significant lowering in serum level of hs-CRP after one-half month and three months.

For dyslipidemic patients in group three who complain from heart failure and receiving atorvastatin therapy, there is a significant lowering in serum level of hs-CRP after one-half month and three months.

If comparison is made between the three groups, we see that there is a significant difference between group one in side and group two and group three in other side in the serum level of hs-CRP in the mid and last readings.

d) The effect of atorvastatin on the serum level of TNF? in pati ents with heart failure Table 7. showed a comparison among the three readings of serum TNF-? in group one patients who complain from heart failure, but they have normal lipid profile and not receiving atorvastatin therapy.

The results showed that there is no significant change in serum level of TNF-? after one-half month and after three months.

In group two patients who have heart failure and normal lipid profile and receiving atorvastatin treatment, we see that there is a significant lowering in the serum level of TNF-? after one-half month and three months of treatment.

The results of group three patients who are dyslipidemic and have heart failure and receiving atorvastatin therapy showed that there is a significant change in the serum level of TNF-? after one-half month and three months of therapy.

e) The effect of atorvastatin on the serum level of adiponectin in patients with heart failure Table 8. showed the results of serum adiponectin in three group patients.

Group one who have heart failue and normal lipid profile and not receiving atorvastatin therapy, group two who have heart failure and normal lipid profile and receiving atorvastatin and group three who are dyslipidemic and have heart failure and receiving atorvastatin therapy.

In all groups, there is no significant change in adiponectin values neither after one-half month nor after three months.

It is evident from the table that there is significant difference in the adiponectin value between group one and group two in side and group two and group three in other side.

f) The effect of atorvastatin on the serum level of total antioxidant status in patients with heart failure Table 9. compare the serum levels of total antioxidant status among the three visits during the follow up duration.

9. Global Journal of Medical Research Volume XII Issue X Version I ear 2012 Y

The Possible Clinical Beneficial Effects of Atorvastatin in Iraqi Patients with Systolic Heart Failure

The results showed that in group one who have heart failure and normal lipid profile and not receiving atorvastatin therapy, there is no significant change in the serum level of total antioxidant status after the treatment duration was completed.

While in group two patients who have the same criteria bur receiving atorvastatin therapy, a significant change in the serum level of total antioxidant status is noted after one-half month and three months.

Group three patients who are dyslipidemic and have heart failure and receiving atorvastatin therapy, the results showed that there is significant change in the serum level of total antioxidant status in the mid and end of therapy duration.

There is a significant difference in the serum level of total antioxidant status between group one who did not receive atorvastatin therapy and group two who receive the therapy for three months.

g) The effect of atorvastatin on the ejection fraction in patients with heart failure Table 10. showed a comparison in the ejection fraction among the three groups.

As we see, in group one, there is no significant change in ejection fraction after the complement of treatment duration.

While in group two who receive atorvastatin therapy, there is a significant increase an ejection fraction in the mid and end of treatment duration.

In group three who receive the atorvastatin therapy, there is also a significant increase in ejection fraction after one-half month and three months of therapy.

A significant difference is noted between group one in side and group two and group three in other side in the value of ejection fraction.

10. IV. Discussion

The last decade has witnessed major advances in the understanding of the molecular mechanisms of HF in response to stress signals. A multitude of extracellular factors and signaling pathways are involved in altering transcriptional regulatory networks controlling cardiac adaptation or maladaptation, and the transition to overt HF (17) . The recognition of the dismal prognosis of heart failure has led to greater efforts to identify the condition early and to optimize risk stratification strategies to guide management (18) . It is becoming increasingly apparent that inflammatory mediators play a crucial role in the development of CHF, and several strategies to counterbalance different aspects of the inflammatory response are considered (19) .

The inflammatory cytokines playing a direct role in worsening HF through the induction of myocyte apoptosis, ventricular dilation, and endothelial dysfunction (20) . In table 2. which shows the lipid profile lipoprotein are not significantly changed at the end of treatment duration, while the serum level of triglyceride and very low density lipoprotein cholesterol are significantly decreased in the mid duration of therapy.

In table 3. which shows the lipid profile of group two who have heart failure and normal lipid profile and receiving atorvastatin therapy, we see that all lipid profile parameters are significantly changed in the mid and end of treatment duration.

All lipid profile parameters for group three who are dyslipidemic and have heart failure are significantly changed after one-half month and three months of atorvastatin therapy, as shown in table 4.

Atorvastatin reduces total-C, LDL-C, VLDL-C, apo B, and TG, and increases HDL-C in patients with hypercholesterolemia and mixed dyslipidemia. Therapeutic response is seen within 2 weeks, and maximum response is usually achieved within 4 weeks and maintained during chronic therapy (21) .

Fasting lipid profile must be assessed in patients with heart failure, the goal of LDL-C is <100 mg/dL (primary goal) or <70 mg/dL (optional goal).

Other possible beneficial effects of statins in CHF patients are also supported. Statin use was associated with improved event-free survival in congestive heart failure patients. Thus, statin treatment in heart failure patients appears promising (22) . Table 5. showed the following:

? Patients suffering from heart failure (group one, group two and group three) have significantly higher serum levels of hs-CRP as compared with control group.

In control group the serum level of hs-CRP is 0.74 mg/L, while they are 11.62, 10.41 and 8.95 for group one, group two and group three respectively.

Elevated levels of the inflammatory marker highsensitivity C-reactive protein (hs-CRP) are associated with increased risk for CVD (23,24) .

Higher hsCRP concentrations occurred in patients with higher New York Heart Association functional class and were related to higher rates of readmission and mortality (25) .

Guidelines for use of hsCRP as an adjunct to global risk prediction, even when levels of LDL-C are low, were issued by the American Heart Association in 2003, and risk algorithms incorporating hsCRP such as the Reynolds Risk Score have been developed and validated (26) .

? Patients suffering from heart failure (group one, group two and group three) have significantly higher parameters of group one patients who have heart failure and normal lipid profile and not receiving atorvastatin therapy, we see that the serum level of total cholesterol, high density lipoprotein cholesterol and low density serum levels of TNF-? as compared with control group.

The serum level of TNF-? in control group patients is 14.63 pg/ml, while they are 40.93, 35.56 and 34.46 for group one, group two and group three respectively.

Chronic heart failure patients have high circulating levels of TNF?, which correlate with the severity of their disease. TNF? has several deleterious effects, including myocardial cell apoptosis, blunted beta-adrenergic signaling, fetal gene activation, endothelial dysfunction, and collagen production. These processes lead to cellular breakdown, decreased cardiac contractility and enhancement of the remodeling process. Moreover, in patients with advanced heart failure, TNF? is associated with cardiac cachexia and rennin-angiotensin system activation and is an independent predictor of mortality (27,28) .

Accumulating evidence suggests that the inflammatory cytokine TNF (tumour necrosis factor)-? plays a pivotal role in the disruption of macrovascular and microvascular circulation both in vivo and in vitro (29) .

? Patients suffering from heart failure (group one, group two and group three) have significantly higher serum levels of adiponectin as compared with control group.

For control group patients, the serum adiponectin level is 7.4 mg/L, while they are 16.58, 12.36 and 18.39 for group one, group two and group three respectively.

Surprisingly, high adiponectin levels in CHF patients are associated with an increased mortality risk and not with lower risk (30) . Serum adiponectin concentrations were stratified according to NYHA class. The more advanced the CHF was (according to NYHA class), the higher the adiponectin concentrations were (31) . It has been suggested that adiponectin predicts mortality and morbidity in HF patients. Given the vasoand cardioprotective properties of adiponectin, these findings cannot be easily explained, and cachexia seems to be the connective link: the reduction in body mass may up-regulate adiponectin's synthesis. As it has been suggested, adiponectin raised levels may just reflect the hyper-catabolic state in severe HF (32) .

Contrary to other adipose-derived hormones, adiponectin concentrations are reduced in subjects with coronary heart diseases, obesity, insulin resistance, or type 2 diabetes (33) .

A number of clinical studies showed a decrease of adiponectin levels in obese humans relative to lean subjects. Plasma adiponectin levels were decreased in diabetic as compared to non-diabetic individuals. Other studies found an inverse relationship between plasma adiponectin and serum triglyceride levels as well as fasting and postprandial plasma glucose concentrations (34) .

All these factors and others results in a big variation in serum adiponectin level among the three groups.

? Patients in all three groups have significantly lower serum level of total antioxidant status as compared with control group.

The serum level of total antioxidant status in control group patients is 1.74, while they are 1.104, 1.053 and 0.966 in group one, group two and group three respectively.

Although the biological mechanisms for progression and ventricular remodeling have yet to be definitively explained, mounting evidence supports the theory that ventricular dysfunction worsens as a consequence of increased reactive oxygen species (ROS) formation (35) .

? All three groups have significantly lower ejection fraction as compared with control group patients.

The ejection fraction in control group is 68.34, while the pretreatment values are 31.43, 33.02 and 30.29 for group one, group two and group three respectively.

Ejection fraction is an useful hemodynamic parameter, that is not always indicative of left ventricular function concerning the peripheral perfusion.

In systolic HF, the primary defect is an impaired ability of the heart to contract. The myocardium is weakened, and the resultant impairment of contractility leads to reduced cardiac output. In addition, systolic HF usually shows an E.F.%<50% and is associated with eccentric left ventricular hypertrophy (36) .

The 3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl-CoA (HMG-CoA) reductase inhibitors (statins) have been unequivocally shown to reduce cardiovascular morbidity and mortality. Their lipid-lowering actions are by reversible and competitive inhibition of the enzyme HMG-CoA reductase, a precursor of cholesterol. It has been suggested that statins appear to have therapeutic benefits in diseases that are unrelated to elevated serum cholesterol levels (37) . This is further evidenced by studies showing that statins may improve cardiovascular performance even in subjects without overt hyperlipidaemia (38,39) . Table 6. showed the effect of atorvastatin on the serum level of hs-CRP of the three groups.

In group one the serum level of hs-CRP is not significantly changed after three months of follow up.

While in group two the serum level is significantly decreased from 10.41, 5.51 to 4.1 (mg/L) at the pretreatment, one-half month and three months respectively.

The results of group three patients also showed a significant decrease in the serum level of hs-CRP in the mid and end of therapy duration.

11. Global Journal of Medical Research Volume XII Issue X Version I ear 2012 Y

The Possible Clinical Beneficial Effects of Atorvastatin in Iraqi Patients with Systolic Heart Failure

The serum level of hs-CRP is decreased from 8.95, 5.48 to 4.51 (mg/L) at the pretreatment, one-half month and three months respectively.

Patients who have lower hsCRP levels after statin therapy have better clinical outcomes regardless of the resultant level of LDL. Reduction in LDL and hsCRP are independent indicators of the success of statins in reducing cardiovascular risk (40) .

The observations that statins therapy reduces serum hsCRP and that serum hsCRP is correlated with cardiovascular risk raises the possibility that the risk reduction with statin therapy may be attributed, at least in part, to antiinflammatory effects (41,42) .

Atorvastatin are among the most widely used Statins in the world. In addition to lowering serum cholesterol, Atorvastatin lowers CRP, an index of inflammation (43,44) .

C-reactive protein has been shown to exert direct adverse effects on the vascular endothelium by reducing nitric-oxide release and increasing endothelin-1 production, as well as by inducing expression of endothelial adhesion molecules. These findings suggest that C-reactive protein may also play a causal role in vascular disease and could therefore be a target of therapy (45) .

It is very difficult to argue not to add hs-CRP measurements to our patient global risk assessment and Framingham CHD risk scores especially in those with two risk factors or strong family history. Patients with high CRP/LDL are in the highest risk category and should be treated, including statins (46) . Table 7. showed the effect of atorvastatin on the serum level of TNF-? of the three groups.

In group one the serum level of TNF-? is not significantly changed after three months of follow up.

While in group two the serum level is significantly decreased from 35.56, 30.16 to 28.8 (pg/ml) at the pretreatment, one-half month and three months respectively.

The results of group three patients also showed a significant decrease in the serum level of TNF-? in the mid and end of therapy duration.

The serum level of TNF-? is decreased from 34.46, 30.28 to 26.51 (pg/ml) at the pretreatment, onehalf month and three months respectively. TNF-a is increased in CHF and seems to reflect the severity of the disease (Levine et al., 1990; Testa et al., 1996; Torre et al., 1996). It has been shown that TNF-a is of prognostic value as there is a relation between the level of TNF-a and mortality (Torre et al., 1996; Rauchhaus et al., 2000). It has been suggested that the strongest prognosticator in the TNF-a system is the soluble TNF receptor 1 (Rauchhaus et al., 2000). It has furthermore been shown that TNF-a is increased especially in cachectic ;[CHF patients (Parissis et al., 1999) (47) .

A large number of studies have shown the beneficial effects of statins with regards to markers of inflammation including TNF-? (tumour necrosis factor?). Overactivity of the immune system has been a matter of ongoing concern in patients with HF for almost two decades now, and, in particular, TNF-? and its soluble receptors have been demonstrated to be markers of an adverse prognosis in patients with this disease (48).

Treatment with atorvastatin markedly ameliorated LV remodelling and LV function and reduced the levels of TNF-? (49) . Table 8. showed the serum levels of adiponectin in all three groups.

The serum level of adiponectin is not significantly changed in anyone of the three groups after the complement of the study duration.

Recently, Qu et al.reported that rosuvastatin but not atorvastatin increased serum adiponectin levels in patients with hypercholesterolaemia, which is consistent with our finding in pati ents with congestive heart failure (50) .

Thus, the potential beneficial effects of statins on adiponectin level may appear less detectable. In addition, some of our patients were hypertensive and they were receiving treatment that may potentially influence the insulin sensitivity (51) .

These factors, combined with the smaller number of our study population, may confound our results. This possible adiponectin-lowering effect of statins warrants elucidation in larger homogenous population.

Table 9. showed the effect of atorvastatin on the serum level of total antioxidant status in the three groups patients.

In group one patients, there is no significant change in the serum level of total antioxidant status at the end of studuy duration.

In group two, as we saw in the table, the serum level of total antioxidant status is significantly increased after one-half month and three months of treatment with atorvastatin.

It is increased from 1.053, 1.934 to 2 at the pretreatment, one-half month and three months respectively.

In group three patients, there is also a significant increase in the serum level of total antioxidant status at the mid and end of treatment duration.

It is increased from 0.966, 1.783 to 1.908 at pretreatment, one-half month and three months respectively.

Statins, in addition to improving lipid profiles, may also lower oxidative stress (52) .

Studies showed that oxidized low density lipoprotein (LDL) is a major correlate of oxidative stress in hypercholesterolemic patients and that statins may reduce oxidative stress by reducing enhanced plasma levels of LDL, which are more susceptible to peroxidation in hypercholesterolemia, and change the LDL structure, making them more resistant to peroxidation.

Some studies further showed that statins may also inhibit NAD(P)H oxidase, thus decreasing the generation of reactive oxygen species (ROS), thereby adding or synergizing the biological effects of antioxidants.

Some studies also showed that statins or their metabolites may act as antioxidants, directly or indirectly by removing "aged LDL", which is more prone to oxidation, from the circulation.

Based on these findings, it is evident that among their properties, statins also possess antioxidant activities (53,54,55) . Table 10. showed the effect of atorvastatin on ejection fraction in all three groups.

In group one patients, the ejection fraction is not significantly increased at the end of study duration.

In group two patients, the ejection fraction is significantly increased at the mid and end of treatment duration.

It is increased from 33.02, 35.02 to 38.68 at the pretreatment, one-half month and three months respectively.

A significant increase in ejection fraction is also seen in group three patients.

It is increased from 30.29, 35.31 to 37.96 at the pretreatment, one-half month and three months interval respectively.

Accurate and reproducible determination of left ventricular (LV) function is essential for the diagnosis, disease stratification, therapeutic guidance, follow-up and estimation of prognosis for the majority of cardiac diseases (56) .

Notably, Atorvastatin treatment significantly suppressed the signs of HF and the number of cardiac myocytes was greatly reduced (57) .

The administration of atorvastatin was found to improve left ventricular ejection fraction, attenuated adverse left ventricular remodeling in patients with nonischemic HF (58) .

12. V. Conclusions

?

| Atorvastatin 40 mg tablet is beneficial in normalizing lipid profile parameters in dyslipidemic patients. ? Atorvastatin is effective in attenuating the inflammatory process which is associated with bad prognosis in congestive heart failure. This effectiveness is recorded through the measurement of the serum level of hs-CRP and TNF-?. ? This treatment is also effective in increasing antioxidant, thus delaying the worsening in heart failure because oxidative stress is directly associated with the bad prognosis process occurring in heart failure. ? Atorvastatin increases the ejection fraction in patients with established heart failure and this may PARAMETER CONTROL GROUP PRETREATMENT chronic heart failure Task force for the diagnosis Circulation 2005;112:1756-1762. 31. Roxana SISU, MD (2006). Adiponectin concentrations inpatients with congestive heartfailure. A Journal of Clinical Medicine, Volume1 No.4. 32. C. Antoniades, A. S. Antonopoulos, D. Tousoulis and C. Stefanadis (2009). Adiponectin: from obesity to cardiovascular disease. obesity reviews 10, 269-279. ONE AND HALF MONTH AFTER TREATMENT THREE MONTHS AFTER TREATMENT TC mg/dl 107.21±6.03 142.73±2.34* 141.27±3.91 139.4±3.82 TG mg/dl 88.43±5.01 127.07±3.82* 111.0±4.0 a 112.6±3.01 HDL-C mg/dl 57.57±0.93 50.33±1.51* 48.73±1.57 49.53±1.53 LDL-C mg/dl 31.95±4.09 66.99±1.98* 70.34±1.54 a 67.35±1.69 VLDL-C 17.69±1.0 25.41±0.76* 22.2±0.8 a 22.52±0.6 34. M. LIPID PROFILE mg/dl alleviate some of the signs and symptoms associated with heart failure. and treatment of chronic heart failure of the European Journal of Heart Failure *significant at P<0.05 as compared with control group. 4 11_22European Society of Cardiology. a significant at P<0.05 as compared with pretreatment. | |||||||

| 12. Rosemary Browne, MD; Barry Weiss, MD (2010). A | |||||||

| Resource for Interprofessional Providers Heart | |||||||

| Failure Diagnosis. ELDER CARE(520) 626-5800. | |||||||

| 13. ScottishIntercollegiate Guidelines Network (2007). | |||||||

| Management | of | chronic | heart | ||||

| Days | after | Acute | CoronarySyndromes | failure.www.sign.ac.uk | |||

| Independently Predict Hospitalization for Heart | 14. Marcio Hiroshi Miname, Raul D. Santos, NeusaForti, | ||||||