1. I. Introduction

ntestinal Perforations are most common surgical emergencies seen worldwide. Despite improvement in diagnosis, antibiotics, surgical treatments and intensive care support, it is still an important cause of mortality in surgical patients. This study was done to know the spectrum of etiology, clinical presentation, management and treatment outcomes of patients admitted with perforation peritonitis in our hospital.

2. II. Materials and Methodology

A prospective study was done over a period of 3 years from January 2011 to December 2013 in SMS medical college and hospital, Jaipur, Rajasthan which included 1400 patients diagnosed with perforation peritonitis.

Incusion criteria: all patients admitted with perforation of gastrointestinal tract were included in this study.

Exclusion criteria: all cases of primary peritonitis and anastamotic leaks were excluded from this study.

All patients were studied in terms of clinical presentation, etiology and site of perforation, surgical treatment, postoperative complications and mortality. All patients following a clinical diagnosis of perforation peritonitis and adequate resuscitation, underwent exploratory laparotomy in emergency setting. At surgery the source of contamination was sought for and controlled. The peritoneal cavity was irrigated with 5-6 litres of warm normal saline and drain was placed. Abdomen was closed with continuous, number one PDS suture material. Although all patients received appropriate perioperative broad spectrum antibiotics, the drug regimen was not uniform.

3. III. Results

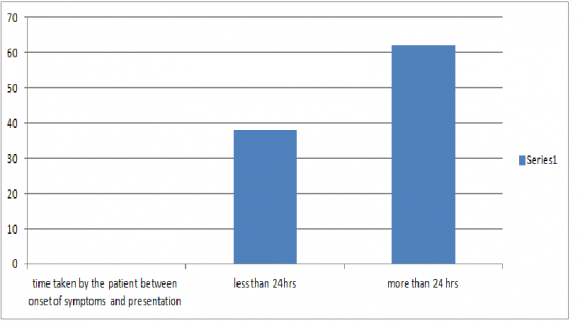

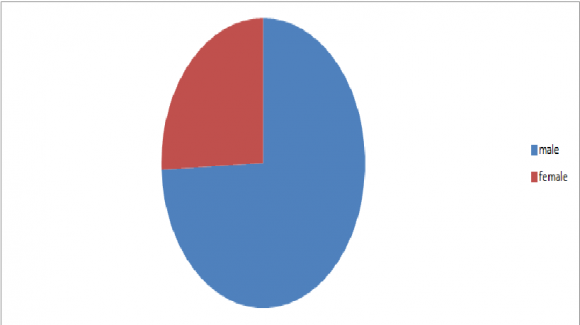

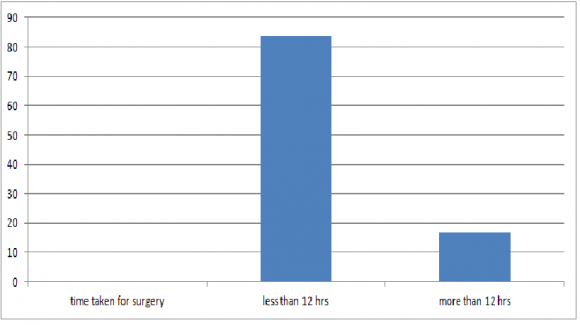

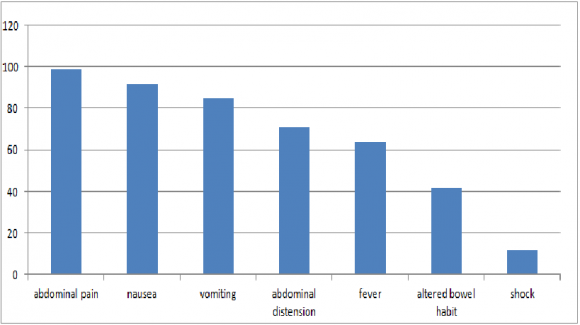

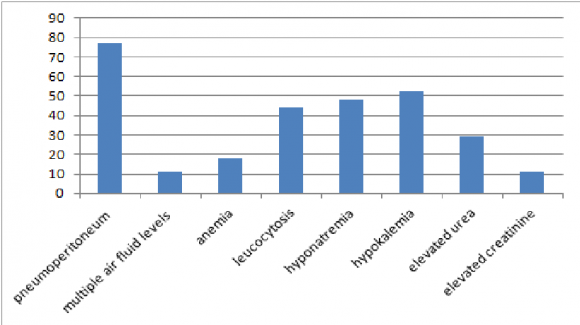

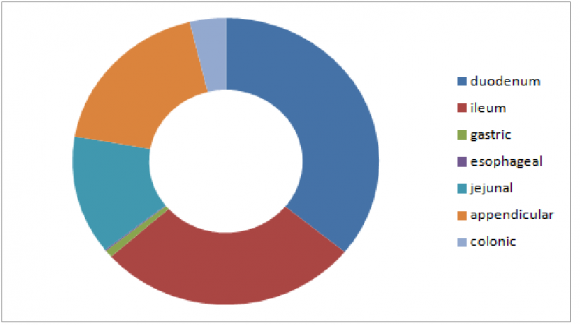

Total of 1400 cases were included in this study. 74.28% being males(1040), with male: female ratio of 2.8. Mean age of presentation was 32 years with minimum age being 17 years and Maximum being 72 years. (figure 1 The time taken by the patient between onset of symptoms and presentation to the hospital was less than 24 hours in 532 cases(38%) and more than 24 hours in 868 cases(62%).(figure 2) : Time taken for resuscitation, diagnosis and preparation for surgery was less than 12 hours in 83.4% cases and more than 12 hours in 16.6% cases Most common symptom with which patient presented was abdominal pain(99%). Site of pain presentation varied with site of perforation. Peptic perforation presented mainly with epigastric pain followed by diffuse abdominal pain, appendicular perforation cases presented initially with either periumbilical pain or right iliac fossa pain. Small bowel and large bowel perforation usually presented with diffuse abdominal pain. Other symptoms included nausea in 92% cases and one or more episodes of vomiting in 85% of cases. Patients also presented with abdominal distension(71%), fever(64%) and altered bowel habit(42%). 12% patients were in shock at the time of initial presentation.(figure 4) Figure 4 : Table showing clinical presentation -abdominal pain in 99%, nausea in 92%, vomiting in 55%, abdominal distension(71%),fever(64%),altered bowel habit(42%) and 12% patients were in shock 77% patients had pneumoperitoneum on erect chest x ray and 11% patients had multiple air fluid levels noted on abdominal x rays. Other Investigations revealed anemia (18%), leucocytosis (44%), hyponatremia (48%), hypokalemia (52%), elevated urea (29%) and creatinine levels (11%).(figure 5) Figure 5 : Table showing investigations-77% had pneumoperitoneum, 11% had multiple air fluid levels, anemia (18%), leucocytosis (44%), hyponatremia (48%), hypokalemia (52%), elevated urea (29%) and creatinine levels(11%) Most common site of perforation noted was duodenum (35.8%) followed by ileum(27.6%). Other sites included gastric (0.85%), esophageal (0.14%), jejuna (13.3%), appendicular (18.4%) and colonic perforation (3.8%). Patients presenting with duodenal perforation mostly had acid peptic disease and history of NSAID intake. Ileal perforation patients predominantly followed typhoid or tuberculosis. Jejunal perforation was seen in patients with blunt trauma abdomen. Malignancy was commonly seen in patients with colonic perforation.(figure 6) Acid peptic disease was most common cause of gastroduodenal perforations(93%). Blunt trauma abdomen was most common etiology behind jejunal perforations(96%). Typhoid (64%) and tuberculosis(31%) mainly resulted in ileal perforations. Malignancy(77%) was most common etiology behind colonic perforations.

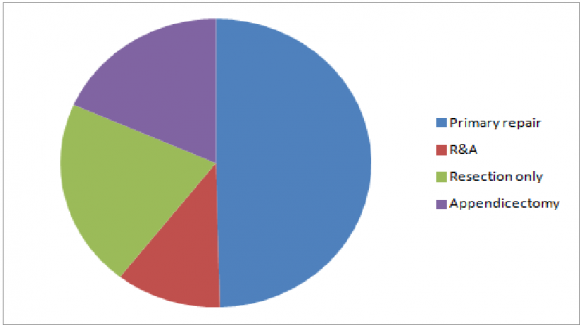

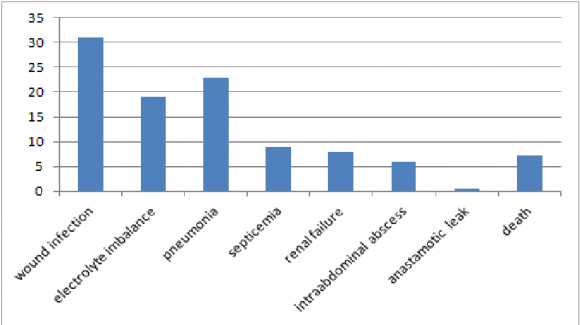

Primary repair was done in 49.6% cases. 11% cases required resection and anastomosis while 21% required resection without anastomosis (ileostomy, colostomy and hartmann procedure). Appendicectomy was done in 18.4% cases.(figure 7) Figure 7 : Procedures done for perforations -Primary repair in 49.6% cases, 11% had resection and anastomosis, 21% required resection without anastomosis (ileostomy, colostomy and hartmann procedure) and Appendicectomy was done in 18.4% cases Complications included wound infection(31%), electrolyte imbalance(19%), pneumonia (23%), septicaemia (9%), renal failure(8%), intraabdominal absc-ess(6%), anastamotic leak(0.5%).Overall mortality was 7.2%.(figure 8) Figure 8 : Complications -wound infection(31%), electrolyte imbalance(19%), pneumonia(23%), septicaemia(9%), renal failure(8%), intraabdominal abscess(6%), anastamotic leak(0.5%). Overall mortality was 7.2%

4. Volume XIV Issue III Version I

5. IV. Discussion

Perforation peritonitis is one of the most important cause of general surgical emergency. In our study of 1400 cases, over 3 years, we noticed mean age of presentation was 32 years with male to female ratio of 2.8. In a study by Adesunkamni et al, they found out that M:F ratio was 3:1 with the overall mean age of 27.6 ± 18.3 years. (1) Patients of perforation peritonitis often presents late to hospital particularly in developing countries like India due to illiteracy, ignorance and lack of adequate medical facilities as is seen in our study where 62% cases came to hospital after 24 hours of onset of their symptoms. By the time the patient presents, he has all typical features of generalized peritonitis with purulent or fecal contamination and many a times patient is in septicaemia with or without shock.

Dorairajan et al conducted study on perforation peritonitis in which they showed the six times higher prevalence of proximal gastrointestinal perforations as compared to perforations of distal gastrointestinal tract.(2) In our study, majority of perforations were in duodenum (35.8%) followed by ileum(27.6%). This was in contrast with data from western world where distal gastrointestinal perforations were more common.(3) Duodenal ulcer Perforation was the most common perforation noticed in our study. Similarly, Gupta S and Kaushik R in their study showed duodenal ulcers in its first part to be the overall most common cause of perforation peritonitis. (6) Khanna et al from Varanasi studied 204 cases of gastrointestinal perforation and found that 108 cases with perforation were due to typhoid and other common pathology included were amoebiasis and tuberculosis. (4) Similarly in our study, we had high incidence of typhoid(64%) and tubercular(31%) ileal perforations. This was in contrary to the western world where a study done in Texas by Noon et al [5] showed almost 50% of cases of gastrointestinal perforation were due to penetrating trauma and not due to infective pathology.

Patients with gastric perforations presents with long term history of NSAIDS intake. Otherwise, it is rare for a gastric ulcer to perforate. (7) Small bowel tuberculosis presents mainly with features of obstruction due to the luminal narrowing caused by hyper plastic tuberculosis and strictures. Multiple ileal perforations are seen in ulcerative type of tuberculosis.(8) Tubercular perforations can be primarily closed or may require stoma formation if associated with poor general condition of the patient or with exceesive fecal contamination. Patient may have associated multiple non passable strictures which may require stricturoplasty at the same time. Decision for the type of management is more or less similar for typhoid enteric perforations and is dependent upon patients general condition and degree of contamination.

With the advent of better surgical care mortality rates in perforation peritonitis have decreased but still it is an important cause of mortality in patients operated in emergency theatres as shown in study by Gupta et al and Ohene Yeboah et al where overall mortality ranges between 6-27% (6,7), where as those associated with gastric perforation were 36% (9), enteric perforation were 17.7% (10) and colorectal perforation were 17.5% (11).

Reasons attributed behind this high mortality rates were delayed presentation which is further aggravated by delay in diagnosis and treatment, which results in high chances of patient developing septicaemia. Advanced age, associated comorbid and respiratory complications worsens the situation. (12)