1. Introduction

lobally in a publication by World Health Organization (WHO) (2016) breast cancer screening is an important practice in preventing breast cancer. Breast cancer is reported to be the second most common cancer in the world and, by far, the most frequent cancer among women with an estimated 1.67 million new cancer cases diagnosed in 2012 (25% of all cancers) (WHO, 2014). It ranked as the fifth cause of death from all cancers and the second most common cause of female cancer-related mortality worldwide (WHO; 2014; Abdel-Aziz et al., 2017; Diab et al., 2018).

Studies have shown a reduction of breast cancer screening has a steady increase in the incidence of breast cancer in Nigeria from15.3per 100,000 in 1976 to 33.6 per 100,000 in 1992 to 52.1 per 100,000 in 2012 (Cancer Research, 2017; Olasehinde et al., 2017;Hanson et al., 2019;El Bcheraoui et al., 2015). Globally, there is a regional variability in the incidence rates of this disease ranging from 27 per 100 000 in African and Middle Eastern countries to 96 per 100 000 in Western Europe and it is, also, the most frequent cause of cancer mortality among women in the less developed regions and the second in the developed countries (Aminisani et al., 2016;National Cancer Institute, 2019;WHO, 2013). In developed countries, however, mortality from breast cancer has been on the decline despite the higher incidence of breast cancer. This is a result of early detection through organized screening programs and effective treatment modalities (Olasehinde et al., 2017;Hanson et al., 2019;El Bcheraoui et al., 2015).

Breast cancer mortality has fallen considerably after the introduction of breast cancer screening in the western countries (WHO, 2013;Cancer Research, 2017). However, the screening is unavailable or less utilized (if available) in the developing countries where the majority of breast cancer deaths are occurred (Pierz et al., 2020;WHO, 2019;Keten et al., 2014;Aminisani et al., 2016).

There is growing evidence that the knowledge of breast cancer screening is more aggressive in Nigeria than in the United States and Europe, including an earlier age of onset and a higher incidence of basal-like and HER2-enriched subtypes of the disease (Ojewole et al., 2017;Sung et al., Rosenberg & Jemal, 2019;Keten et al., 2014). When detected early and treated promptly, these cancers have a high cure rate in a well-resourced high-functioning health system (Pruitt et al., 2020). The aetiology of breast cancer is not well known (American Cancer Society, 2018). However, several risk factors have been shown to impact an individual's risk of developing breast cancer and their ultimate prognosis. These well-established risk factors include older age, family history, oral contraceptives, null parity, hormone replacement therapy, and early menarche, late first fullterm pregnancy, late menopause, dense breast tissue, and tobacco smoking (Sung, Siege, Rosenberg & Jemal, 2019; Diab et al., 2018). Breast cancer is curable when detected at an early stage. Women with early stage disease have an excellent prognosis with a 100% five years survival rate for stage 0 and I, while those with metastatic disease at diagnosis have a five years survival of around 20%, so it is important for women to be aware of the importance of early detection through screening (Diab et al., 2018).

According to a report by Federal Ministry of Health in Nigeria (2015) early recognition and detection of Breast Cancer can play a significant role in reducing cancer morbidity and mortality as it gives more treatment options and increases survival rate if diagnosed early. Early detection of BC can be achieved by one of the following screening methods: breast selfexamination (BSE), clinical breast examination (CBE), and mammography (Breast Cancer Now, 2019; Cancer Research, 2017; American Cancer Society, 2017). Although BSE alone is inadequate for early detection of BC, it is recommended by the American Cancer Society as an option for women starting from the early 20s of age as a method for breast awareness and early recognition and detection of BC. Unlike mammography and CBE, BSE does not require hospital visit and expertise, and it is cheap, simple, and non-invasive method that can performed by women themselves at home (Agodirin et al., 2017). According to American Cancer Society (2018) recommendations, women should be aware how their breasts usually feel and report any breast changes without delay to their healthcare providers. Several previous studies have shown that female students had poor awareness and negative attitudes concerning BC and BSE. Such negative indicators continue to be present as a recent descriptive study among women in a community found that those women to have inadequate knowledge regarding BC and BSE (45.5%), fairly positive attitudes (56.3%), and low frequent practice of BSE (37.5%) (Ojewole et al., 2017;Nwaneri et al., 2017;Cancer Research, 2017;Denny et al., 2012).

Worldwide, many interventional studies have been conducted to increase knwoeldge of BC screening and practice of BSE among women (Keten et al., 2014;CDC, 2019;Anderson et al., 2018). For instance, a study by Abdel-Aziz et al (2017) evaluated the effectiveness of a breast health awareness program on knowledge of BC and BSE practice among women in Rural Nigeria based on the health belief model. The study revealed that the educational intervention had a positive impact on increasing BC knowledge among the participants. Similar findings were revealed among some young Nigerian women and Saudi women (Abdel-Aziz et al., 2017). Therefore, all recommendations were to increase the level of the women's knowledge about BC and emphasize the importance of increasing BC awareness and promoting the practice of BSE for early detection of breast abnormalities (Hanson et

2. b) Study Design

This study adopted a cross-sectional study using a quantitative method of data collection on the knowledge and practice of breast cancer screening among women at Enugu South.

3. c) Study Population

The study population for this study consisted of adult women aged 15 years at Enugu South LGA. The estimated population of women is 11,407.

4. d) Inclusion Criteria

This study includes; i. All women aged 15 years and above at Enugu South who gave in their consent for the study. ii. Any individual who volunteered to provide information vital to the research among women at Enugu South.

5. e) Exclusion Criteria

This study excludes;

i. Any woman aged 15 years and above at Enugu South who refuses to give in her consent for the study. ii. Any woman aged 15 years and above at Enugu South who is sick, psychologically malnourished, disabled and on admission to the hospital during the time of data collection of the study.

6. f) Sample Size

The sample size for this study is 406 (see appendix A) g) Sampling procedure A multistage random sampling technique was used. The procedure was as follows: Stage 1: Selection of Communities; Simple random sampling was used to select 5 Communities from the total number of communities in Enugu South LGA. Stage 2: Selection of Villages: Two villages each were selected from each of the five selected communities. Also Systematic random sampling was once more is used to select households on each street to give every household an equal chance of selection. This would be done by the researcher. Finally, simple random sampling was used to select 3 females of reproductive age (15years and above) in each household giving a total of 406 respondents.

7. h) Instrument for Data Collection

A self administered semi structured questionnaire was used for the study on the knowledge and practice of breast cancer screening among women at Enugu South. The questionnaire was designed for simplicity and assimilation by the respondents.

8. i) Validity of the Instrument

The research instrument being the questionnaire which was used for data collection was developed by researcher and submitted to the project supervisor as well as two experts from department of public health for face validity and proper scrutiny in order to ensure that the questionnaire met the objectives of study.

9. j) Reliability of Instrument

Reliability of the instrument was determined using test retest method. Copies of the questionnaire were given to some women outside the area of study by the researcher because this area for reliability testing shared similar characteristics with Enugu South LGA that was used for the study. Chrombach alpha test was used to test for the reliability coefficient of the questionnaire.

10. k) Method of Data Collection

Data was obtained using a self administered based semi structured questionnaire. This was done with the aid of Two (2) field assistants who were Hired and trained to aid the researcher in the data collection process. The purpose of the research was explained face to face to the respondents before distribution of the questionnaires to them.

11. l) Method of Data Analysis

The Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS) was used in the analysis of the data gotten from the study. Results were expressed in percentages, frequencies, tables and charts (Descriptive Statistics). Chi square test was then used to analyze the hypothesis of the study p = (0.05).

12. m) Ethical Consideration

A letter of introduction and ethical clearance was obtained from the Department of Nursing Sciences, University of Nigeria Nsukka before the research was conducted. The purpose of the research was explained to each respondent and verbal informed consent obtained from them before inclusion into the study. Also, anonymity of the respondents was also assured and ensured. The confidentiality of the information they gave was also be maintained.

13. III.

14. Results

A total of Four hundred and six (406) copies of questionnaires were distributed for the study and three hundred and ninety-six (396) questionnaires were retrieved and they were properly filled and crosschecked for correctness and were used for the purpose of the analysis.

15. a) Socio-demographic Characteristics

From table 1 below, it was posited that 34.0% (135) of the women represented age groups between 45-49, 30.3% (120) of the women were 50 years and above, 21.4% (85) of the respondents were 35-44 years of age, 8.2% (32) were aged 25-34, and 6.1% (24) aged 15-24 years. 63.2% (250) of the women were of Igbo origin, 29.1% (115) reported 'others', 5.1% (20) Yoruba, and 2.7% (11) Hausa/Fulani. 66.9% (265) of the respondents were Christians, 14.7% (58) listed religions not included in the options but label 'others', 11.4% (45) Traditional and 6.9% (28) Muslim. 35.9% (142) of the women had a child, 8.9% (35) had two children, 26.6% (105) had 3 children and above, and 28.7% (113) had no children. Concerning the education level of the respondents, 39.0% (154) had attained tertiary education, 28.9% (115) for secondary education levels, 22.1% (88) had attained primary education levels and just 9.9% (39) had informal education levels. Students among the respondents totaled 24.7% (98), 25.2% (100) were civil servants, 23.9% (95) 'farmers', 5.9% (23) identified as traders, and 20.3% (80) 'others'. 35.8% (142) reported 'yes' concerning monthly income satisfaction, while 64.2% (254) of the women said "no". 42.8% (169) of the respondents were single, 35.2% (139) married, 16.5% (65) separated, and 5.6% (22) widowed. When the women were asked about their household level of income, 16.5% (65) reported income above 100,000, 20.9% (83) between 2,000-10,000, 10.2% (40) earned from 11,000-30,000, 2.9% (11) 1-1,000, 19.9% (79) listed 'other' income levels, 18.6% (74) earned figures from 61,000-100,000, and 11.0% (44) from 31,000-60,000. 47.4% (188) of the respondents affirmed they had a health plan at a healthcare center, while 52.6% (208) reported they did not. 1. below), 23.0% (87) of the respondents reported 'newspaper/magazines' as their sources of information on breast cancer screening, 19.0% (75) said "Tv/radio programs", 18.9% (75) reported social media, 3.8% (15) health practitioners, 14.9% (59) parents/family, 11.4% (45) school, and 9.0% (36) reported sources not listed but label 'others'. 40.3% (159) of the women affirmed they had been part of a breast cancer screening, 32.5% (129) reported 'no', and 27.3% (108) were not sure. Respondents who accepted to have undergone breast cancer screening reported to have done so between 6 months to a year (26.4%), 24.4% (39) reported 'longer than a year', 21.9% (35) said "4-6 months", 14.8% (23) reported 2-3 months, and 12.6% (20) reported in less than a month. 52.5% (208) of the women affirmed that mammography is a method used to screen for breast cancer, while 47.5% (188) replied "no". Women in Enugu-South accepted that breast self examination is encouraged as part of a breast education program, while 15.3% (60) said "no". When the respondents were asked if lump swelling under armpit, bleeding or discharge and nipple retraction is a warning sign of breast cancer, majority agreed (78.8%), while 21.2% (84) reported otherwise. 3 below, majority of the respondents reportedly demonstrated their approval to undergo breast cancer screening if offered a chance (92.5%), while 7.5% (30) denied. 53.9% (214) of the respondents reported 'Yes" when they were asked if they had been advised by a physician to screen the breast prior to the time of this investigation, 26.4% (105) could not remember, and 19.7% (78) said "No". 47.0% (186) of the respondents had not screened for breast cancer or any infection relating to the breast before filling the questionnaire, 36.3% (144) replied "Yes", and 16.7% (66) reportedly could not remember. 32.7% (47) of the respondents who reported 'yes' said they last screened for periods longer than a year, 24.6% (35) reported 4-6 months ago, 18.1% (26) said "6 months to a year", 16.6% (24) reported 'in less than a month', and 8.0% (12) reported 2-3 months ago. When they were asked concerning reasons for breast cancer screening, over half of the women (57.3%) reported 'for prevention', 18.1% (26) explained that they were presented with symptoms, 16.6% (24) just decided to go for the examination, and 8.0% (12) as a result of cases in the family respectively. 85.4% (338) of the women had never had an abnormal test result in breast cancer screening, while 14.4% (58) reported 'Yes'.

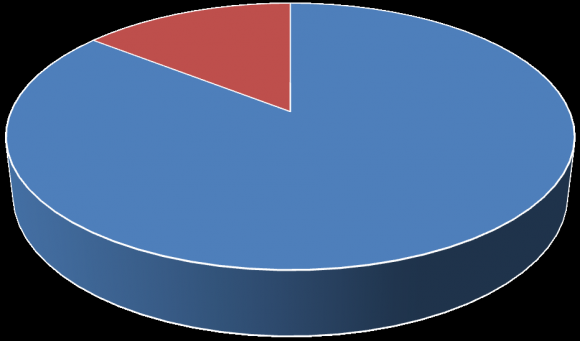

16. AWARENESS OF BREAST CANCER SCREENING

17. e) Association between the knowledge of Breast cancer screening and the Socio demographic characteristics of females

Table 5 below showed the results for the test of a statistically significant association between sociodemographic characteristics and knowledge of breast cancer screening among women in Enugu South Local Government Area, Enugu State. There was a statistically significant association between age of women and knowledge of breast cancer screening (p= 0.010). Given the association between marital status of women and knowledge of breast cancer screening among women in the study population (p=0.300), there was no significant association. On the hypothesis between number of children (parity) and knowledge of breast cancer screening among women in primal population, There was also a statistically significant association (p=0.0008). Given the association between level of income of women and knowledge of breast cancer screening in the study population, there was a statistically significant association (p=0.0092). There was a statistically significant association between level of education and knowledge of breast cancer screening in the study population (p=0.0327). Finally, there was no statistically significant association between occupation and knowledge of breast cancer screening in the study population (p=0.127).

Table 5: Association between the knowledge of Breast cancer screening and the Socio demographic characteristics of females f) Association between the knowledge of Breast cancer screening and the Practice of breast cancer screening among women at Enugu South Table 6 below showed the results for the test of a statistically significant association between knowledge of breast cancer screening and practice of breast cancer screening among women. There was a statistically significant association between good knowledge and practice of breast cancer screening among women (p= 0.0032). IV.

18. Discussion

Findings of this study respect to the socio demographic characteristics of the respondents, 34.0% of the women were in the age range of 45-49 years and this is comparable to findings of Ogunkorode et al. (2017) which showed that 35% of the population studied was between the ages of 45-49 years. Also, observation from this study showed that majority of the participants in the breast cancer screening survey were Christians et al. (2015) where majority, of the respondents had good knowledge about breast cancer. However this as in contrast to the level of knowledge reported among students in Turkey where low knowledge level was reported (Hanson et al., 2019). In the study, 23.0% of the women listed newspaper/magazines as their source of information on breast cancer screening. This could be due to some campaigns and awareness on breast cancer screening on mainstream media. Additionally, 40.3% of the respondents had reportedly undergone breast cancer screening. This is however in contrast with a study by Aminisani et al. (2016) Knowledge and Practice of Breast Cancer Screening Among Women in Enugu South, Nigeria corroborate this finding and this is also in agreement with the finding of Akande et al. (2015) where majority of the students were well informed about mammography as a screening method for breast cancer. This was also observed by Kami?ska et al. (2015) and finding is similar to the results of another study conducted. From the study 92.5% of the women demonstrated their approval to utilize breast screening services if offered a chance these points out the lack of access towards breast cancer screening among respondents. A previous study by Diab et al. (2018) suggested similar findings among respondents in a Kenyan study. 53.9% of the women accepted they had been advised by a physician to screen the breast prior to the time of this investigation. A study by Poehls (2019) corroborates this finding and demonstrated that physicians actively sensitized their female patients on breast cancer screening. This study revealed that 85.4% of the women had never had an abnormal test result in Breast cancer screening as supported by several studies (Kanaga et al., 2011;Karabay et al. 2018;Al-Hussami, 2014).

The finding of the study revealed that the commonest factor affecting their practice of breast cancer screening was 'distance to facility' (19.3%). This goes in consistence with a study by Poehls (2019) on the practice of breast cancer screening screenings. Another study by Hedge et al. ( 2018) in agreement to this finding and suggests that 26.6% of women who underwent breast cancer screenings listed affecting factors such as financial constraints, followed by distance to facility.

Findings from this study regarding the association between Socio-demographic characteristics and practice of Breast cancer screening among women revealed that Age is significantly associated with practice of breast cancer screening screening among women(p = 0.010). Study shows that older women groups utilized breast cancer screening relative to younger groups. This goes in line with a study by Hedge et al. (2018) which found age to be associated with practice of breast cancer screening (p = 0.00271). Further investigation into the study demonstrated that marital status is not significantly associated with the practice of breast cancer screening (p = 0.300). This goes in line with a report published by Al-Amri (2015) that there was no significant association. This implies that women who wanted to utilize screenings did, irrespective of their marital status. Although certain studies suggested some women did not participate in screening exercises due to permission/acceptance from their husbands (Chigbu et al., 2017;Nnebue et al., 2018). Also, from the study among women in Enugu South, it was posited that there was a significant association between number of children (Parity) and practice of breast cancer screening among women in the study population (p =0.0008). Few studies support this finding (Adejumo et al., 2018;Chigbu et al., 2017;Nnebue et al., 2018;Olasehinde et al., 2017). Considering the hypothesis between level of income of women and practice of breast cancer screening, there a significant association (p =0.0092). This goes in consistence to a previous study by Al-Amri (2015). This signifies that women with better level of income were more likely to utilize breast cancer screening services. This study also indicates that women with higher level of education were significantly involved in breast cancer screening than those with low levels of education. Women without any formal education level hardly came in for screening. This indicates that more enlightened a person is, the more likely they were to undertake breast cancer screenings. Hence level of education of women and practice of breast cancer screening are significantly associated (p = 0.0327). A preceding study by Al-Amri (2015) confirms this finding. Findings of this study showed an association between knowledge of breast cancer screening and practice of breast cancer screening among female women(p= 0.00532).This implies that women who were well informed know the importance and would easily seek breast cancer screening as opposed to those who lacked information. A study by Poehls (2019) corroborates this finding on the association between knowledge of breast cancer screening and practice of breast cancer screening.

V.

19. Conclusion

Breast cancer is a major health concern and remains the most common malignancy in women worldwide. In this study, It was seen that age, educational level, level of income, marital status and knowledge were all related with practice of breast cancer screening among the women in Enugu South. Findings from this study establish that even though a number of women showed considerable knowledge of breast cancer screening, several others were deficient of relevant information. Women need to be encouraged to perform BCS regularly and earnestly report any abnormality to the health care providers since they generally showed willingness to participate if afforded an opportunity. Also, perceived factors affecting breast cancer screening practices such as distance to facilities must be put into consideration to ease uptake. Emphasis must be made on the importance and effectiveness of breast cancer screening. Also Policies must be implemented to accommodate low income earners and encourage breast cancer screening.

| speaking. | |

| al., 2019; El Bcheraoui | |

| et al., 2015; Agodirin et al., 2017). Early detection and | |

| prompt attention as a result of adequate knowledge and | |

| awareness about breast cancer and screening methods | |

| go a long way in reducing the associated high mortality | |

| rate (Elobaid et al., 2014; Aduayi et al., 2016; Keten et | |

| al., 2014). | |

| Recent findings from a Nigerian Breast Cancer | |

| Study show that the majority of patients have advanced | |

| stage at diagnosis than has been reported in other | |

| populations (Arisegi et al., 2019; Dodo et al., 2016; | |

| Akande et al., 2015). This underscores the need for | |

| systems-level interventions to downstage breast cancer | |

| in Nigeria (Dodo et al., 2016; Akande et al., 2015; Pruitt | |

| et al., 2020). The causes of late-stage diagnosis are | |

| complex and, in addition to aggressive molecular | |

| subtypes, include lack of access to comprehensive | |

| screening and preventive care as well as social and | |

| cultural factors such as alternative healing, financial | |

| concerns, and lack of education (Breast Cancer Now, | |

| 2019; Pierz et al., 2020; Akande et al., 2015). Delayed | |

| diagnosis of breast cancer in Nigeria has been well | |

| documented and has a significant impact on breast | |

| cancer morbidity and mortality. Improved awareness | |

| campaigns and better understanding of the causes of | |

| delay in care is critical to develop relevant and effective | |

| screening measures. It is due to this that the current | |

| study aimed to investigate the knowledge and practice | |

| of breast cancer screening among women in Enugu | |

| South, Nigeria | |

| II. | Methods |

| a) Study Setting | |

| Enugu South is a Local Government Area of | |

| Enugu State, Nigeria. Its headquarters are in the town of | |

| Uwani. It has an area of 67 km 2 and a population of | |

| 198,723 at the 2006 census. The postal code of the area | |

| is 400. The geographic coordinates of Enugu South is | |

| given as 5 o 57'40"N 8 o 42'39"E. The people of Enugu | |

| South are majorly farmers. Enugu South is a major | |

| producer of banana and plantain for the Nigerian | |

| market. It is known for the Christianity and Igbo | |

| Characteristics | Frequency (n=396) | Percentage (%) |

| Age | ||

| 15-24 | 24 | 6.1 |

| 25-34 | 32 | 8.2 |

| 35-44 | 85 | 21.4 |

| 45-49 | 135 | 34.0 |

| 50 and Above | 120 | 30.3 |

| Total | 396 | 100 |

| Ethnicity | ||

| Igbo | 250 | 63.2 |

| Hausa/Fulani | 20 | 5.1 |

| Yoruba | 11 | 2.7 |

| Others | 115 | 29.1 |

| Total | 396 | 100 |

| Religion | ||

| Christianity | 265 | 66.9 |

| Muslim | 28 | 6.9 |

| Traditional | 45 | 11.4 |

| Others | 58 | 14.7 |

| Total | 396 | 100 |

| Number of Children (Parity) | ||

| None | 113 | 28.7 |

| 1 | 142 | 35.9 |

| 2 | 35 | 8.9 |

| 3 and above | 105 | 26.6 |

| Total | 396 | 100 |

| Education level | ||

| Informal education | 39 | 9.9 |

| Primary | 88 | 22.1 |

| Secondary | 115 | 28.9 |

| Tertiary | 154 | 39.0 |

| Total | 396 | 100 |

| Occupation | ||

| Student | 98 | 24.7 |

| Farmer | 95 | 23.9 |

| Trader | 23 | 5.9 |

| Civil servant | 100 | 25.2 |

| Others | 80 | 20.3 |

| Total | 396 | 100 |

| Variables |

| Variable | Frequency (n=396) | Percentage (%) |

| Do you Practice breast cancer screening if offered a | ||

| chance? | ||

| Yes | 366 | 92.5 |

| No | 30 | 7.5 |

| Total | 396 | 100 |

| Have any physician advised you to screen the breast before? | ||

| Yes | 214 | 53.9 |

| No | 78 | 19.7 |

| Cannot Remember | 105 | 26.4 |

| Total | 396 | 100 |

| Variable | Frequency (n=396) | Percentage (%) |

| Which of the following related as possible factors affecting | ||

| your Utility of Breast cancer screening | ||

| Distance to facility | 82 | 19.3 |

| Cultural related factors | 42 | 10.0 |

| Family/Husband Acceptance | 79 | 18.7 |

| Financial Constraints | 56 | 13.3 |

| Lack of Information | 58 | 13.8 |

| Religious Factors | 2 | 0.5 |

| Behavior of Health workers | 48 | 11.3 |

| Practice of breast cancer | knowledge of breast cancer screening | X2 | P-value | Decision | |

| screening | Good Knowledge | Poor | |||

| (%) | Knowledge (%) | ||||

| Yes | 89.0% | 11.0% | |||

| 1.9376 | 0.0032 | Sig | |||

| No | 32.8% | 67.2% | |||

| Volume XXIII Issue I Version I |

| D D D D ) F |

| ( |

| Medical Research |

| © 2023 Global Journ als |