1. Introduction

uminant productivity around the world is majorily affected by trematode parasitism (Vercruysse and Claerebout 2001). Among them, Fasciolosis gains public concern not only due to its prevalence and economic significance to animal stock in all continents (Scheweizer et al., 2005, Mungube et al., 2006) but also to its zoonotic aspect. Bovine Fasciolosis is an impedent in profitable bovine farming and for butchers and consumers too. Parasite of genus Fasciola i.e Fasciola hepatica and Fasciola gigantica is the causative agent of Fasciolosis which occur in a wide range of definitive hosts. Over the last decade there has been a substantial increase in the number of fasciolosis cases recorded. It is spurred on by both environmental changes (warmer, wetter climate) and man-made modifications such as an increase in animal movements and intensification of livestock farming (Mas- Coma et al., 2005).

According to Annual Reports of Department of Animal Husbandry, Dairying and Fishries, species -wise incidence of Bovine Fasciolosis in India is tabulated as under: While comparing the apparent prevalence of liver fluke infection, detected by liver, faeces and bile examination it has been reported that examination of liver or bile samples was more sensitive than faecal examination (Braun et al., 1995 andKumar et al., 2002).Thus the abattoir study was carried out to determine the prevalence.

2. II. Material and Methods

A two-year prospective systematic sampling study was undertaken from January 2014 to January 2016 to determine the relative occurrence of Fasciola infection in the livers of cattle presented to six abattoirs across the Kashmir. Samples were taken from the three studied localities i.e., Hazratbal, Parimpoora, and Gouskimber of Srinagar district but sampling effort was more important in Parimpoora locality, where four slaughterhouses were closely located.

The sample size was calculated using the formula given by Thrustfield, M. (2005).

3. ?? = 1 96 2 1

Where n = required sample size P exp = expected prevalence= 50% d = desired absolute precision=5% Hence, d = 0.05 and p= 0.5 (50%).

The expected prevalence in the study area was 55 % (Akhoun and Peer, 2014). Thus the minimum desired annual sample size was calculated to 381. However, due to drastic floods only 316 cattle were examined in Year 2014 as collection areas were inaccessible and sample size was extended to 396 in Year 2015. The age of each animal was confirmed by looking at the physical appearance of body and examining the dental pad and incisor teeth (Cockrill, 1974). The data was collected according to predesigned proforma: Young (1Yr-3Yrs), adult (3-6Yrs) and aged (Above 6 years). During survey the gender and breed of animals was also recorded. ? Assessment of Body condition Body scoring of the cattle was made based on the method described by Nicholson and Butterworth (1986). Each scoring were given number from 1(L-, very lean) to 9 (F+, very fat) and these scores finally included under three body condition scores, good, medium and poor.

4. ? Season

On the basis of temperature and precipitation, four seasons in a year recognized in Kashmir valley are: winter (December to February); spring (March to May); summer (June to August); autumn (September to November) (Dar et al., 2002).

5. b) Postmortem examination ? Types of infection

Infection based on causative agent were classified as Fasciola hepatica, Fasciola gigantica, mixed Fasciola species (Fasciola hepatica, Fasciola gigantica) infection.

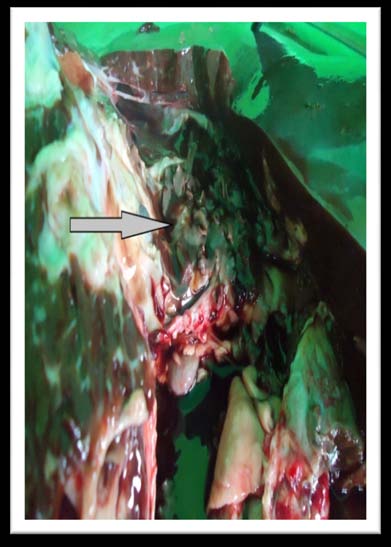

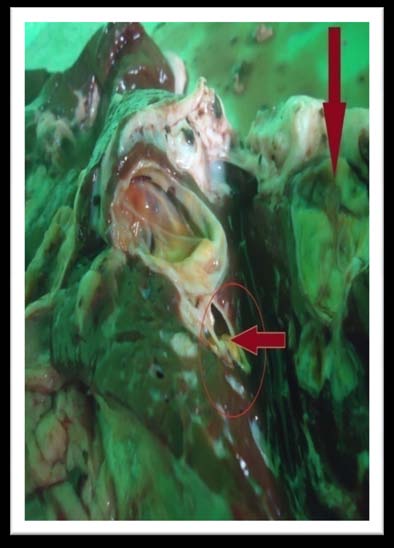

6. c) Postmortem fluke recovery

Worms were recovered from infected livers by squeezing them manually to macerate the parenchyma and the flukes were carefully removed and placed in petridish containing 0.15M Dubecco's PBS buffer (pH 7.3) for initial washing. The flukes were stored in collection vials containing PBS and were transported to the laboratory of Department of Zoology, University of Kashmir, Srinagar. Fasciolids were identified primarily on differences in body shape and size of the adults, with the smaller F. hepatica exhibiting wide and defined shoulders compared to the slender F. gigantica having less defined shoulders and shorter cephalic cones (Soulsby, 1986). For permanent slide preparation flukes were rapidly killed in 70% ethyl alcohol to avoid shrinkage. The flukes were then transferred to vials containing 6-10% formalin for preservation. Flukes were stained with Borax Carmine, dehydrated in ascending grades of ethanol, cleared in Xylene and mounted in Balsam Canada and viewed under monocular light microscope.

7. d) Data Analysis

Data was recorded, entered and managed into MS Excel work sheet and analyzed using Minitab Version 13.Prevalence was calculated as percentage of infected among the examined samples. Chi square test was employed to examine the effect of above mentioned epidemiological determinants on the level of parasitism in host. In all statistical analysis, confidence level was held at 95% and P-value is <0.05 (at 5% level of significance) was considered as significant.

8. IV. Results

Fasciolosis in an area is influenced by a multifactorial system which comprises both definitive and intermediate hosts, parasite and environmental effects. Numerous factors (both intrinsic and extrinsic) form an association posing a potential epidemiological threat and it is important that the existence and localization of such an association should be recognized beforehand so that the situation can be brought under control. Thus in this portion of result, these factors have be assessed and potential reason behind the association have been well documented

9. Overall Prevalence (Table 1)

The overall prevalence of Fasciolosis for the period of two years (2014-2015) was found to be 26.84% in the current study areas. In 2015, the percentage prevalence was higher (27.02%) than in 2014 (25.31%). There was an increase of 1.71% in prevalence rate from 2014 to 2015.But difference in prevalence rate was not statistically significant (p>0.05) as there was sampling error in year 2014 because of scarcity of data collection for a period of 2 months (September and October) due to Floods that affected the whole valley.

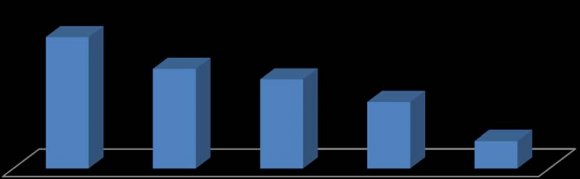

The result of current study indicated that Fasciolosis in cattle is spread relatively with moderate prevalence rate of 26.84% in the study area as compared to high prevalence of 51.42%,42.06% and Month-wise prevalence (Fig. 1)

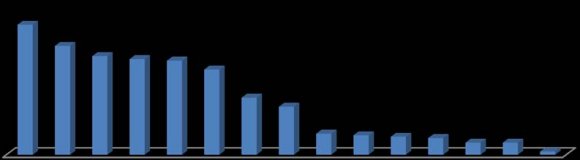

The results revealed that the lowest prevalence of Fasciolosis for Year 2014 was in the month of May (14.2%) and highest being in the month of August (35.8%).However in Year 2015, the prevalence rate was highest in the month of September (44.66%) followed by October (39.66%) and lowest in May (9.3%). Moreover, the infection was reported throughout the year due to resistance of metacercariae for desiccation, especially during the dry season and continued presence of the shallow water, enough vegetation and humidity for continued exposure of the animals to encysted metacercariae and no restriction on cattle grazing habits and movement between the infected and treated localities which was also suggested by El Bahy, 1998.

These On seasonal basis, the current study showed maximum spread of disease in Autumn Season i.e. 33.33% and 40% in Year 2014 and 2015 respectively. The minimum infection was recorded in spring season showing prevalence of 20% and 12.9% in consecutive studied years. There was no statistically significant difference between seasons in year 2014 which has already been stated could be attributed to skipping the data of two months due to natural disaster Kashmir valley faced. However statistically significant difference was observed between seasons in year 2015. This difference could be due to a variety of weather condition in each year. The highest prevalence in autumn was also reported by Chaudhri et al. 1993

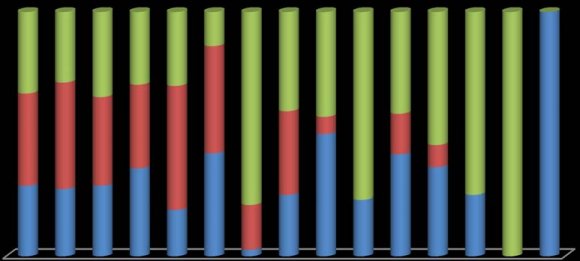

10. Distribution on the basis of infection type (Table 3)

Of the total 192 affected livers by fasciolosis, 149 (77.60%), 24 (12.5%) and 19 (9.89%) respectively showed Fasciola gigantica, Fasciola hepatica and mixed infection (Fasciola hepatica and Fasciola gigantica).

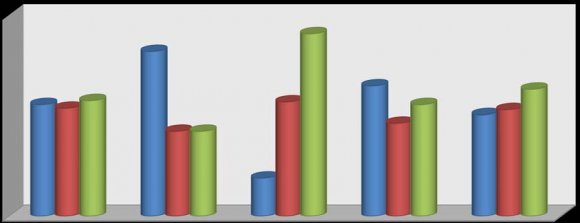

The finding of this study was in consistence with the earlier investigation by Ashrafi et al. 2004 Genderwise prevalence (Table 5) Out of 531 males and 183 females slaughtered during the survey period, males won by retaining lesser infection of 19.96% and were par to females who showed higher prevalence of 46.99%. The difference was highly significant and thus revealed sex as determinant influencing the prevalence of Fasciolosis rate. Our findings are in agreement with results of Daniel 1995; Molina et In the current studied abattoirs, the number of slaughtered male cattles (531) was far higher than the females (183). The number of positive females was higher in proportion than males even if the number of female cattle that come to abattoir were fewer in number. These results were in consistent to Kara et al. 2009. High infection rate in females can be multifactorial like high stress during parturition period (Spithill et al. 1999), weak and malnourished making them more susceptible to infection (Blood and Radostits, 2000) or due to the feeding conditions i.e females are generally being let loose to graze freely in pastures. The other possible reason for the same could be that the most of people traditionally feed their lactating cows with grasses during dry season which are grown around rivers and marshy areas for the sake of getting high milk yield as suggested by Gracy et al. 1999

11. Breedwise prevalence of Fasciolosis (Table7)

Out of the total 71 cattle examined, 213 were reared locally and 501 were imported from other states to the valley for slaughter purpose. The prevalence of fasciolosis was 40.80% and 20.90%for local and nonlocal breed cattle, respectively. There was statistically significant (? 2 = 29.06, P = 0.000) association of fasciolosis with breeds. Our results are in agreement with study conducted by Teklu et al. 2015. This diference in prevalence based on breed might be due to the management of the animals as most of the local animals were reared in the extensive system of management which makes them easily susceptible to the parasites

| YEAR | EX. | INF. | PREV | ? 2 (P-Value) |

| 2014 | 316 | 80 | 25.31% | 0.183 |

| 2015 | 396 | 107 | 27.02% | 0.669 |

| Total | 714 | 192 | 26.84% |

| Year 2016 | |||||||||||

| Volume XVI Issue III Version I ( D D D D ) | 80 70 | 27.7 | 29.41% | 36.5% | 31.03% | ||||||

| 60 | |||||||||||

| 50 40 30 | 34.2% | 21.05% | 25% 19.04% | 10.34% | 9.3% | 20% 10.5% | 24.13% 35.8% 44.66% | 33.33% 39.66% | 30.7% | 2015 2014 | |

| 20 | 25.6% | ||||||||||

| 20.45% | 16.12% | ||||||||||

| 10 | 14.28% | ||||||||||

| 0 | NS | NS | |||||||||

| JAN FEB MAR APR MAY JUNE JULY AUG SEP. OCT. NOV. DEC. | |||||||||||

| Figure 1: Monthwise prevalence of Fasiolosis (2014-2015) | |||||||||||

| © 2 016 Global Journals Inc. (US) | |||||||||||

| Year | 2014 | 2015 | ||||

| Season | Ex. | Inf. | Prev. | Ex. | Inf. | Prev. |

| Spring | 115 | 23 | 20% | 82 | 10 | 12.9% |

| Summer | 99 | 26 | 26.26% | 102 | 20 | 19.6% |

| Autumn | 12 | 4 | 33.33% | 146 | 59 | 40% |

| Winter | 90 | 27 | 30% | 66 | 18 | 27.27% |

| Infection Type | Infected | Prev. Among Infected Ones (N=192) | Overall Prevalence (N=714) |

| F. gigantica | 149 | 77.60% | 20.86% |

| F. hepatica | 24 | 12.5% | 3.361% |

| Mixed | 19 | 9.89% | 2.66% |

| ?2 | 254.29(p=0.000) | 186.22(p=0.000) | |

| Age-wise distribution (Table4) | |||

| Out of 714 cattles, 166 heads were of age | |||

| group <1-3Years, 396 of age between 3-6 years and | |||

| 152 having age >6 Years. Among these 3 age | |||

| categories, prevalence of Fasciolain livers was highest | |||

| in >3-6 years age group (30.30%) followed by age | |||

| group >6 years (28.28%) and least infection in bovines | |||

| of age 1 | |||

| Age | Ex. | Inf. | Prevalence | ? 2 p-Value |

| 1Yr-3Yrs | 166 | 29 | 17.46% | 9.991 |

| 3Yrs-6Yrs | 396 | 120 | 30.30% | 0.007 |

| >6Yrs | 152 | 43 | 28.28%% |

| Examined | Infected | Prevalence | |

| Males | 531 | 106 | 19.96% |

| Females | 183 | 86 | 46.99% |

| ?2 (p-value) | 49.221(0.000) | ||

| Association of body condition with infection (Table 6) | |||

| Among all examined animals (n = 714), 30.53% | |||

| (n = 218) were marked as poor (body score 1-3), | |||

| 35.05% (n =250) as Medium (4-6) and 34.44% (n = | |||

| 246) as Good (7-9) body conditions. 42.66% of infection | |||

| (n i | |||

| Body Condition | Ex. | Inf. | Prevalence | ? 2 p-Value |

| Poor | 218 | 93 | 42.66% | 41.223 |

| Medium | 250 | 56 | 22.40% | 0.000 |

| Good | 246 | 43 | 17.47% |

| Year 2016 | ||||

| Volume XVI Issue III Version I | ||||

| D D D D ) | ||||

| ( G | ||||

| Breed | Ex. | Inf. | Prevalence | ? 2 p-Value |

| Locals | 213 | 87 | 40.80% | 29.06 0.000 |

| Non-locals | 501 | 105 | 20.90% | |

| © 2016 Global Journals Inc. (US) |