1. I. Introduction

umors of neurogenic origin make up 20% of such tumors in adults and 25% in children and the vast majority are benign. They are classified as tumors originating from nerve cells (ganglioneuroma and neuroblastoma) and nerve sheath tumors (Schwannomas and neurofibromas) [1]. Schwannoma (neurilemmoma) was recognized and identified for the first time in 1910, by Verocay, and is defined as a neoplasm exclusively composed of Schwann cells of the nerve sheath, which generally affect sensitive fascicles of the cranial and intercostal nerves [2].

Schwannomas are derived from Schwann cells belonging to the peripheral nervous system with the function of producing myelin for axons [3]. They occur in close proximity to the nerve of origin, are grayish encapsulated masses, and can present cystic areas [3].

They are usually benign, grow slowly, emerge at any age, though they are more common in people over 40 years old, and show no preference for sex or ethnicity [3].

They occur most commonly as cranial nerve VIII tumors (acoustic neuroma) [3]. Although they are asymptomatic and are discovered accidentally by imaging tests, when extradural, their most common presentation is through tumor masses that can compress surrounding structures, becoming symptomatic in the process, as is the case of schwannomas from intrathoracic organs [3][4][5][6]. Most tumors of intrathoracic organs originate in the posterior mediastinum (posterior paraspinal groove), and only 5.4% arise from the chest wall [7].

They are difficult to diagnose and suspicion of diagnosis is the result of analyzing the format of surgical specimens, cell arrangement and immunohistochemical detection of the S-100 protein [2].

A mutation of the tumor suppressor gene NF2 shows a close relation with the presence of schwannoma [3].

The recommended treatment is surgical resection by thoracotomy or thoracoscopy. In the medical literature, few cases of mediastinal schwannomas exclusively treated by thoracoscopy have been reported [3,5,6].

2. II. Methods

This review article was based on electronic searches in the PubMed, Scielo, Scopus and Web of Science databases. We collected data from case reports, cohort studies and literary reviews, using the keywords: schwannoma, neuroma, neurilemmoma, nerve tissue neoplasm, thoracotomy, thoracoscopy and mediastinal neoplasms. The method presented the following guiding question: "What are the main results and scientific evidence identified in national and international bibliographic production, concerning the therapeutic approach of intrathoracic schwannoma?".

In the initial survey, the articles were evaluated by seven researchers (authors) according to the following inclusion criteria: articles published in Portuguese, English or Spanish, using the selected keyword combinations, published between 1969 and 2015 that were readily accessible. After the initial selection of material, articles repeated in different databases and that featured other tumors occurring in intrathoracic organs unrelated to schwannoma were excluded. The final material was composed of 47 scientific articles.

3. III. Results

4. a) Epidemiology

Neurogenic tumors account for about 20% of all mediastinal neoplasms in adults and about 25% in children. Schwannomas and neurofibromas are neurogenic tumors of the posterior mediastinum [6,7]. The majority of neurogenic tumors in the posterior mediastinum originate from intrathoracic organs, while only 5.4% grow on the chest wall [8]. Schwannomas most commonly originate from the extremities, the head and neck [9]. Though these tumors occur in adults, they are often observed at younger ages [10]. They usually affect people in their thirties and forties, though at present, patient ranges from six to 78 years old and no predilection for sex or ethnicity has been reported [6].

5. b) Pathology

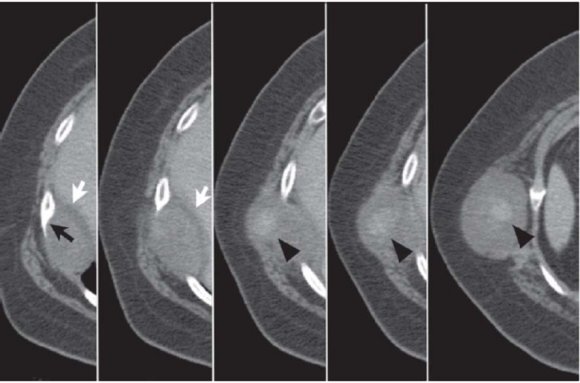

Typically, the intercostal nerve lies between the innermost intercostal and the internal intercostal muscles. In addition, it lies along the subcostal groove together with the intercostal blood vessels. It is known that when the neurilemmoma grows toward the external chest wall, it may be blocked by the bottom edge of the adjacent rib [11].

Because of this, schwannomas that originate from the intercostal nerve can project lumps into the thoracic cavity. It is worth pointing out that there are two possible forms of growth, tumors that develop within and outside the thoracic wall [11,12].

The first is the neurilemmoma, which arises from the lateral cutaneous branch of main intercostal nerve. On the chest wall, the intercostal nerve traverses a subcostal course and provides lateral cutaneous branches around the medial axillary line, while passing through the subcutaneous layers prior to and after this line [11,13].

The second possibility is an anatomical variation. The intercostal nerve can trace a path away from the subcostal groove, blocking the growth of external neurilemmoma [11].

Schwannoma is a neoplasm originated in the Schwann cells of the nerve sheath that usually affect sensitive fascicles of the cranial and intercostal nerves [12]. Cranial nerve VIII is the most affected [13]. They are encapsulated hard greyish masses, that remain in close proximity to the nerve of origin, and areas of cystic changes and xanthomatosis have been reported [3,14].

These tumors present two distinct growth patterns: Antoni A and Antoni B, can present multiple degenerative changes, such as nuclear pleomorphism, xanthomatous change and vascular hyalinization, with no prognostic differentiation [3]. The growth pattern of cells present in Antoni A regions shows elongated fusiform nuclei with cytoplasmic expansions arranged in bundles in areas of moderate to high cellularity with minimal stroma matrix; "nuclear-free zones" of expansions are situated between the regions of palisaded nuclei associated with Verocay bodies [12]. The Antoni B growth pattern exhibits thinner cells loosely arranged within microcystic spaces and showing myxoid change. The cells present minimal cytoplasm, within which thin ill-defined extensions are observed that are not arranged into bundles [13]. The material between the cells is highly hydrated, and is matched by the increased T2 signal visualized on a MRI [14,15].

In most cases, a mutation of the tumor suppressor gene NF2 occurs on chromosome 22. There are three types of NF2, distinguished according to their clinical presentation and severity: Wishart, Gardner and mosaic type NF2. The Wishart type appears in childhood or late adolescence and consists of bilateral vestibular schwannomas associated with medullary tumors, whereas the Gardner type appears later, is less debilitating, and presents as bilateral vestibular schwannomas, with few meningiomas [15].

Malignant transformation is extremely rare in this type of tumor, although local recurrence following resection may be incomplete [14].

6. c) Clinical presentation and diagnosis

Thoracic schwannoma tumor growth is slow, which results in a poor clinical condition, with few or no symptoms, especially in the early stages. However, when the tumor reaches large proportions, commonly presenting as a bulky mediastinal mass, symptoms can arise as a consequence of the compression site, such as superior vena cava syndrome, dyspnea or dysphagia [3,16].

Sometimes schwannomas can develop into the trachea, through the intercartilaginous membrane, forming an hourglass shaped tumor. In the presence of bone erosion, severe pain or pathological fractures are common [13]. In about 10% of cases, growth can exceed the intervertebral foramen and compromise the spinal canal by in an hourglass shaped growth that causes paresthesia or paralysis. When this occurs, symptoms of intramedullary extension are present in 60% of cases [17][18][19].

In addition, patients can present more severe signs, such as hemoptysis, when the tracheobronchial tree is affected, or gastrointestinal bleeding, is cases involving the esophagus. Dysphonia can occur with vagus nerve involvement prior to the origin of the recurrent nerve [20][21][22].

Schwannomas usually occur alone, arising from any cranial or peripheral nerve, and it is very rare to find multiple schwannomas arising from a single intercostal nerve [23].

The investigation of intrathoracic schwannomas begins with a full medical history and physical examination, followed by imaging tests. The majority of lesions are diagnosed in young adults with no predominance of sex [3].

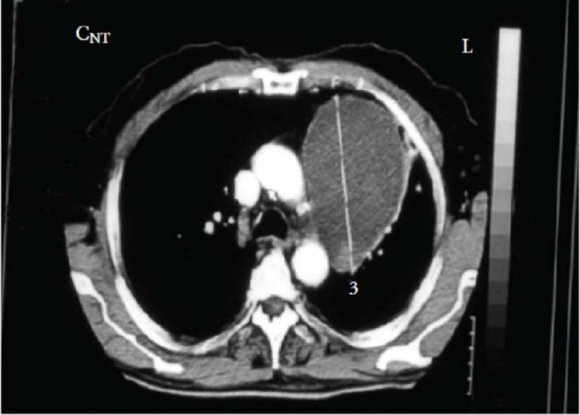

Posterior-lateral (Fig. 1) and profile chest radiographs are commonly the first examinations used to detect any changes. They generally delimit the portion of the mediastinum affected, but do not determine tumor density, invasion of the spinal canal or adjacent structures [22].

Regarding computed tomography (CT) (Figs. 2 and 3), the tumor normally presents as a homogeneous mass, with soft tissue density [23][24][25]. The presence of hypodense areas corresponds to areas of necrosis or hemorrhage. Neurilemmomas are characterized by several pathological areas: hypocellular areas adjacent to densely cellular areas or proximal to collagen or xanthomatous change; resulting in CT images with heterodense areas [22,24]. In CT, lesion appearance can be highly variable, but is usually well circumscribed [25]. In contrast, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) shows better definition of the involvement of nerve plexi, vertebrae and the spinal canal. Hyperintense areas in T2 images correspond to cystic degeneration in the tumor [26].

MRI must be performed in patients with suspicion of neurogenic tumors of the posterior mediastinum, to exclude extension of the tumor in the intraspinal region [23]. As a result, from the moment the tumor develops, typical MRI signals (high intensity) can be observed that which enable a very precise diagnosis. Thus, preoperative radiological assessment alone is sufficient, i.e. fine needle aspiration is unnecessary [27].

By defining tumor extension more precisely, MRI enables preoperative planning that is more sensitive than CT at delineating the presence or absence of invasion through the neural foramen and the degree of involvement of the vertebral canal [25]. The diagnosis can be confirmed intraoperatively and by histopathological study [24].

Ancient schwannoma is a rare variant of the tumor that presents degenerative histological changes, which can lead to an incorrect diagnosis of malignancy. This rare status can simulate lung neoplasms in chest xrays and CTs [28].

The radiological features of ancient schwannoma are not well defined due to its rarity. However, the long-term progression of the tumor leads to characteristic degenerative changes, such as cystic formation, calcification, hemorrhage and hyalinization3. Its appearance on CT and MRI is typical of this type of tumor [22,24]. Solid components encapsulated with cystic areas, or the presence of cystic masses with marginal growth or with solid nodular components that present calcifications are observed [29,30].

Some authors suggest that a recommendation for surgical treatment must be considered when a patient has a mass hypervascular in soft tissues, containing amorphous calcification on the simple scan and cystic areas on the MRI [24,25]. The suggestion is that calcification of soft tissue, which is visible in a simple scan, is a characteristic indicative of this pathological entity [31].

A definitive diagnosis is only possible after histopathological examination. The most significant histological characteristics of these tumors are the presence of a high degree of nuclear atypia, with the presence of atypical hyperchromatic polymorphic cells, and nuclei that frequently containing multiple lobes [28,32].

Fine needle biopsy can be useful in the diagnosis of anterior and posterior mediastinal tumors, but this technique is difficult to execute in the middle mediastinum, given that the amount of material is limited, thus it is not recommended for diagnosing these processes [22,33].

Microscopy reveals two distinct types of tissue, according to the Antonio classification: type A, corresponding to the cellular area; and type B, corresponding to the myxoid area. These two forms are usually associated in the same tumor [19].

Benign schwannomas are distinguished by the presence of a biphasic pattern (Antoni A and B) with the presence of Verocay bodies in type A pattern. These bodies are formed by two parallel lines of nuclei with a space between them that is virtually anuclear [34].

Immunohistochemical analysis shows immunoreactivity for S-100 protein, as reported for neurogenic tumors [35].

7. IV. Discussion a) Thoracotomy x Thoracoscopy

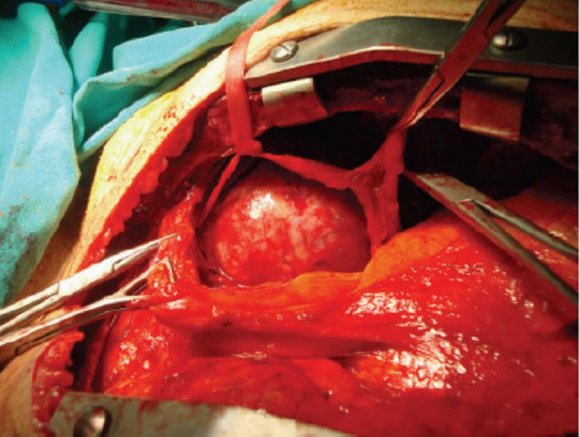

The treatment of choice for mediastinal schwannomas is resection by videothoracoscopy or open thoracotomy [36]. Thus, surgery is the main therapeutic route for neurogenic tumors of the mediastinum, and complete surgical resection is considered the gold standard [37].

The management of neurilemmomas located in the mediastinum is determined by the findings of CT or MRI exams. However, these findings only refer to intrathoracic tumors, or those that extend into intervertebral channel, due to visualization difficulties [25,38].

Benign neurogenic tumors rarely reappear and simple enucleation is sufficient, such that no adjuvant therapy is required. The challenge is to preserve nerve function, particularly when the tumor occurs on the phrenic or vagus nerve [37].

Preservation of the recurrent laryngeal nerve is essential, to prevent paralysis of the same, i.e. postoperative dysphonia. In resections of vagus nerve below the origin of the recurrent nerve, no cardiac, bronchial or gastrointestinal changes have been observed [39,40].

When the tumors originate on the intercostal nerves, if necessary, the nerve root can be sacrificed, resulting in relatively minor deficit [37].

In addition to the normal risks of thoracic surgery, such as hemorrhaging, infection and pulmonary morbidity, certain neurological complications can arise due to resection [26]. Among these, those that should be mentioned include deficits like Horner's syndrome, partial sympathectomy, recurrent laryngeal nerve injury and paraplegia [37].

Thoracotomy (Fig. 4) is a viable approach for masses in the middle and posterior mediastinum, and it is also adequate for the anterior mediastinum if the mass is fully contained within one hemithorax and does not cross the midline [3].

Video-assisted thoracoscopic surgery (VATS) was fully disseminated in the 1980s following technological improvements and consolidation of the laparoscopic technique. Indications for resection by videothoracoscopy include: biopsy to exclude malignancy, relief of compressive symptoms, to prevent extension of a tumor into the spinal foramen, and to prevent malignancy [6][7][8]. In video-assisted surgery the patient is positioned as per a lateral thoracotomy, and the camera is introduced into the fifth intercostal space, posteriorly for anterior mediastinal masses and anteriorly for posterior masses. Other accesses depend on the location of the mass. Postoperative recovery of neurological function depends on the type of surgery [3,7,16].

Among the majority of reported cases that exclusively used the VATS technique to resect mediastinal masses, a high degree of success was obtained, demonstrating the safety of the procedure in the hands of properly trained surgeons. When compared with thoracotomy, VATS requires smaller incisions, which reduces pain, causes fewer and less severe pulmonary complications, shortens hospitalization and promotes earlier return to activities and aesthetic gains. Prognosis after surgery is good, but local recurrence can occur following incomplete resection of the lesion [3].

If complete resection cannot be performed, a common situation when dealing with malignant tumors, postoperative radiation therapy is the recommended course of action. Occasionally, postoperative chemotherapy can also be effective [24,25].

The majority of mediastinal neurogenic tumors occur in the posterior compartment, and the best surgical approach is a standard thoracotomy. However, VATS is an excellent choice for simple neurogenic tumors [41,42].

Tumor excision is curative, since the recurrence of benign schwannomas is unusual [22,43]. Malignant degeneration of a benign tumor has been described, but it is rare [44]. Although rare and infrequent, intrathoracic schwannomas of the vagus nerve should be included in the differential diagnosis of mediastinal tumors [22].

Conducting a preoperative assessment regarding intraspinal involvement is essential, in order to decrease the risk of hemorrhaging into the spinal canal and spinal cord damage [30][31][32]. When a tumor is identified in this region, the recommended approach is thoracic surgery and neurosurgery. Initially, this process was performed in phases, beginning with a laminectomy, followed by a thoracotomy at a later date [18,45].

Currently, the preferred option is performing the procedure in a single operation, in which combined resection is the method of choice. This can be performed through separate incisions or a shared incision [4]. A single incision, with a vertical component along the spine, and a curvilinear lateral extension, allows access to both specialties. Thus, a laminectomy can be performed to remove the intraspinal component, while the thoracic component can be excised by thoracotomy [10][11][12][13]. This allows for excision of the entire mass and minimizes the risk of undetectable hemorrhage inside the spinal canal, where a hemotoma could result in neurological deficit [18,45].

More recently, Vallieres et aI. described an approach that uses posterior microneurosurgical techniques and anterior VATS techniques to perform a minimally invasive complete resection [46].

A careful preoperative assessment is essential to clarify whether there is any spinal canal or neural foramen involvement, so that the risks of hemorrhage and neurological damage are reduced significantly [4][5][6]. Treatment involves complete surgical resection via thoracotomy or thoracoscopy with neurosurgical exploration, to verify whether tumor has extended into the spinal canal [27,28]. Although recurrence is rare and patients present a good prognosis, since the tumor is benign, when dealing with malignant neurogenic neoplasms, prognosis is poor [3].

Fine needle biopsy can be performed; however, a precise diagnosis may not be possible due to limited cellularity. This raises the possibility of a misdiagnosis of malignancy, since the appearance of histological degenerative changes can occur. Surgical excision of the mass is the gold standard for the diagnosis and treatment of these potentially resectable tumors [47].

8. Volume XVI Issue IV Version I

9. V. Conclusion

Intrathoracic schwannoma is often asymptomatic, and the lesion is usually detected in routine imaging tests. Thus, its diagnosis is a challenge and should not be discarded as diagnostic hypothesis in the presence of mediastinal masses.

Magnetic resonance imaging is the preferred image examination for preoperative planning, since it presents clearer observation of the involvement of nervous plexi, vertebrae and the spinal canal.

The recommended treatment remains resection by thoracotomy or VATS, and recurrence of benign neurogenic tumors following the procedure is rare and does not require adjuvant therapy.

In addition to the risks common to any thoracic surgery, neurological complications should be taken into consideration during the surgical approach.

Among the surgical approach, open surgery continues to be the most commonly used method for treatment. VATS assists in realization of biopsies to exclude malignancy, to relieve compressive symptoms and to prevent extension of the tumor into the spinal foramen.

In cases where VATS is used for tumor resection, prognosis is good, but relapse can occur when the resection is incomplete and complementary treatment with chemotherapy or radiotherapy is recommended.

In the medical literature, few cases of thoracoscopic mediastinal schwannomas exclusively treated by VATS have been reported. However, there is space for all the surgical modalities, and the method should be applied on a case-by-case basis. In this context, doctor and patient should be similarly engaged in choosing the best method to achieve the expected result.