1.

Equine Lung Worm: A Systematic Review Nuraddis Ibrahim Summary-Lungworms are parasitic nematode worms of the order Strongylidae that infest the lungs of vertebrates. Dictyocaulus arnfieldi is the true lungworm affecting donkeys, horses, mules and zebras and is found throughout the world.

Dictyocaulus arnfeildi can cause severe coughing in horses and because patency is unusual in horse (but not in donkeys) differential diagnosis in disease due to other respiratory disease can be difficult. Adult Dictyocaulus worms are slender, medium sized roundworms, up to 8 centimeter long. Females are about one third longer than males. They have a whitish to grayish color. Dictyocaulus worms have a direct lifecycle, i.e. there are no intermediate hosts involved. The pathogenic effects of lungworm depends on their location within the respiratory tract, the number of infective larvae ingested, the animal immune status, on the nutritional status and age of the host. Despite the prevalence of patent D. arnifieldi infection in donkeys, overt clinical signs are rarely seen; however, on close examination slight hyperpnoea and harsh lung sounds may be detected. Diagnosis is based on clinical signs, epidemiology, presence of first-stage larvae in feces, and necropsy of animals in the same herd or flock. Bronchoscopy and radiography may be helpful. Larvae are not found in the faeces of animals in the prepatent or postpatent phases and usually not in the reinfection phenomenon. ELISA tests are available in some laboratories. Bronchial lavage can reveal Dictyocaulus arnifieldi infections in horses. The concern of lungworm in Ethiopia is increasing and is now to be a major problem of equines. Routine deworming of horses and donkeys may help prevent cross infection when kept together. Reducing pasture contamination with infective larvae is a key preventative measure that can be achieved to a large extent with adequate management measures. Rotational grazing with a change interval of 4 days and keeping the paddocks empty for at least 40 days significantly reduces pasture contamination.

2. I. Introduction

quines are one of the most important and mostly intimately associated with man. They have enormous contribution through their involvement in different social and economic sectors. Equines play an important role as working animals in many parts of the world, for packing, riding, carting and ploughing. Equine power is very crucial in both rural and urban transport system. This is because of its cheapness and availability and so provides the best alternative transport means in places where the road network is insufficiently developed and the landscape is rugged and mountainous and in the cities where narrow streets prevent easy delivery of merchandise (Feseha et al., 1991).

In Ethiopia equines have been as animals of burden for long period of time and still render valuable services mostly as pack animals throughout the country particularly in areas where modern means of transportation are absent, unaffordable or inaccessible (Abayneh et al., 2002).

In some areas of North West Kenya and Southern Ethiopia, donkey meat is a delicacy and the milk believed to treat whooping cough (Fred and Pascal, 2006).

Even though mules and donkeys have often been described as sturdy animals; they succumb to a variety of diseases and a number of other unhealthy circumstances. Among these, parasitic infection is a major cause of illness (Sapakota, 2009). Lungworms are widely distributed throughout the world providing nearly perfect conditions for their survival and development but are particularly common in countries with temperate climates, and in the highlands of tropical and subtropical countries. Dictyocaulidae are known to exist in East Africa and South Africa (Hansen and Perry, 1996).

Dictyocaulus arnfieldi is the true lungworm affecting donkeys, horses, ponies and zebras and is found throughout the world (Smith, 2009). Donkeys and their crosses (Mules) are the natural hosts for lungworm and the condition in horses is usually found in those that have been in the company of donkeys and mules (Rose and Hodgson, 2000). This review article supports researchers to more understand the equine lung worm disease and factors influencing the disease occurrence under Ethiopian condition. It also helps policy makers to draw sound decisions in order to improve the control policy. The review paper gives information to farmers and cattle rearing people regarding equine lung worm disease.

And therefore, the objectives of this paper are to give background information on the disease and recommend modern control measures.

3. II. Definition and Etiology of Lungworm

Lungworms are parasitic nematode worms of the order Strongylidae that infest the lungs of vertebrates. The taxonomy of this parasite is belonging to kingdom Animalia, phylum Nematode, class Secernentea, family Dictyocaulidae, genus Dictyocaulus E and species of Dictyocaulus arnfieldi (Johnson et al., 2003). An infection of lower respiratory tract, usually resulting in bronchitis or pneumonia can be caused by several parasitic nematodes, including D. viviparous in cattle and deer; D. arnfeildi in horses and donkeys; D. filaria, Protostrongylus rufescens, and Mullarius capillaries in sheep and goats; Metastrongylus apri in pigs; Filaroides (Oslerus) osleri in dogs; and Aelurostrongylus absrtusus and Capillaria aerophila in cats, other lungworm infection occur but less common (Fraser, 2000).

Dictyocaulus arnfieldi is the true lungworm affecting donkeys, horses, mules and zebras and is found throughout the world (Smith, 2009). It is a relatively well adopted parasite of donkeys but tend to be quite pathogenic in horses, where this parasite is endemic (Bowman, 2003).

The first three lungworm listed above belong to

4. III. Morphology of Dictyocaulus Arnfieldi

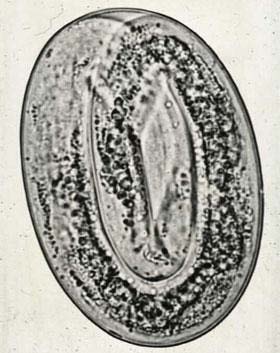

Adult Dictyocaulus worms are slender, medium sized roundworms, up to 8 centimeter long. Females are about one third longer than males. They have a whitish to grayish color. As in other roundworms, the body of these worms is covered with a cuticle, which is flexible but rather tough. The worms have a tubular digestive system with two openings, the mouth and the anus. They also have a nervous system but no excretory organs and no circulatory system, i.e. neither a heart nor blood vessels. The female ovaries are large and the uteri end in an opening called the vulva. Males have a copulatory bursa with two short and thick spicules for attaching to the female during copulation. The eggs of Dictyocaulus arnfieldi are approximately 60x90 micrometers. They have an ovoid shape and contain a fully developed L1 larva (Junquera, 2014). The epidemiology of lungworm disease is largely concerned with factors determining the number of intensive larvae on the pasture and the rate at which they accumulate. The third stage larvae are long living in damp and cool surroundings. Warm and wet summers give rise to heavier burdens in the follow autumn and spring. Horses are not the favorite host of this parasite and do not usually transmit the disease to other horses. In most instances, horses acquire this disease when pastured with donkeys (Blood et al., 1999).

Under optimal condition the larvae may survive in the pasture for a year. They are quite resistant to cold although it generally delays their maturations. They can withstand temperature of 4-5 degree Celsius; Larvae can over winter in cold climates (Blood et al., 2000).

Most outbreak of verminous pneumonia occur during cool season specially autumn and early winter because the larvae stages of the causative worms tolerate and prefer low temperatures (Hansen and Perry, 1996).

The natural host of the parasite is donkey, and comparably, large numbers of parasites can accumulate in the lungs of this host without clinical signs. Donkeys and mules can act as a reservoir for horses (Beelitz et al., 1996). Pilobolus fungi may play a role in the dissemination of D. arnifieldi larvae from faeces, as D. viviparus. D. arnfieldi is found worldwide, particularly in areas with heavy rainfall (Urquhart et al., 1999).

5. b) Life Cycle

The detailed life cycle is not fully known, but is considered to be similar to that of bovine lungworm, Dictyocaulus viviparus except in the following respect.

The adult worms are most often found in the small bronchi and their eggs, containing the first stage larvae, hatch soon after being passed in the faeces (Urquhart et al., 1999).

Dictyocaulus worms have a direct lifecycle, i.e. The pathogenic effects of lungworm depends on their location within the respiratory tract, the number of infective larvae ingested, the animal immune status, on the nutritional status and age of the host (Blood et al., 1989; Fraser, 2000). Larvae migrating through the alveoli and bronchioles produce an inflammatory response, which may block small bronchi and bronchioles with inflammatory exudates. The bronchi contain fluid and immature, latter adult worms and the exudates they produce also block the bronchi. Secondary bacterial pneumonia and concurrent viral infections are of the complication of Dictyocaulosis (Howard, 1993). The major pathologic changes which results from primary infection may be divided into three stages. These are the prepatent stages, where blockage of small bronchi and bronchioles by eosinophilic exudates produced in response to the developing and migrating larvae. The patent stage, when adult worms cause bronchitis and primary pneumonia development occurs. The post patent phase is when adult worms are expelled and majority of animals gradually recover. The pathological changes seen in the lungs during necropsy are atelectasis, emphysema, petechial hemorrhage and lung consolidation (Aiello and Mays, 1998).

6. d) Clinical Signs

Despite the prevalence of patent D. arnifieldi infection in donkeys, overt clinical signs are rarely seen; however, on close examination slight hyperpnoea and harsh lung sounds may be detected. This absence of significant clinical abnormality may be partly a reflection of the fact that donkeys are rarely required to perform sustained exercise. Infection is much less prevalent in horses. However, patent infections may develop in foals and these are not usually associated with clinical signs.

In older horses infections rarely become patent but are often associated with persistent coughing and an increased respiratory rate (Urquhart et al., 1999).

Donkeys usually show no disease signs and can be silent carriers and shedders of this parasite, which causes clinical signs in horses (Johnson et al., 2003).

7. e) Diagnosis

Diagnosis is based on clinical signs, epidemiology, presence of first-stage larvae in feces, and necropsy of animals in the same herd or flock. Bronchoscopy and radiography may be helpful. Larvae are not found in the faeces of animals in the prepatent or postpatent phases and usually not in the reinfection phenomenon. ELISA tests are available in some laboratories. Bronchial lavage can reveal Dictyocaulus arnifieldi infections in horses (Stuart, 2012).

Verminous pneumonia is easily confused clinically with bacterial bronchopneumonia, with acute and chronic interstitial pneumonia, and with viral pneumonia. The disease usually occurs in outbreak form in summer and autumn (Blood et al., 1999). The diagnostic methods of lungworms are described as the following ways in details.

8. f) Clinical Diagnosis

Typical signs and symptoms are heavy coughing (often paroxysmal), accelerated and/or difficult breathing and nasal discharge. Affected animals lose appetite and weight. Severe infections can also cause pneumonia (lung inflammation), emphysema (over inflation of the alveoli), and pulmonary edema (liquid accumulation in the airways). Adult livestock usually develops resistance and if re-infected may not show clinical signs but continue shedding larvae that contaminate their environment (Junquera, 2014).

9. g) Faecal Examination

A convenient method for recovering larvae is a modification of the Baermann technique in which large faecal samples (5-10 grams) are wrapped in tissue paper or cheese cloth and suspended or placed in water contained in a beaker. The water at the bottom of the beaker is examined for larvae after 4 hours; in heavy infections, larvae may be present within 30 minutes.

10. Bronchial lavage can reveal Dictyocaulus arnfieldi infections in horses (Stuart, 2012). h) Serological Diagnosis

Enzyme Linked Immuno Sorbent Assay (ELISA) test can demonstrate antibodies from five weeks after the animals have been exposed and it may be useful in identifying infected animals when heavy burdens of worms do not generate and larvae in the feces. This time need to perform an ELISA depends on the availability of antigen-coated microstate-plates. If such plates can be provided; the result can be obtained within four hours after the serum has been prepared. If not, plates have to be coated with antigen for up to 16 hours (Boon et al., 1984).

11. IV. Necropsy Findings

The morphological change in the lungs include wide spread areas of collapsed tissue of dark pink color, hemorrhagic bronchitis with much fluid filling all the air passed and enlargement of the regional lymph nodes. Histologically, the characteristic lesions are edema, eosinophilic infiltration, debris and larvae in the bronchioles and alveoli. The most obvious lesions at necropsy are discrete patches of over inflation. The bronchial epithelium is hyperplasic and heavily infiltrated by inflammatory cells, particularly eosinophils (Reinecke, 1989). Reducing pasture contamination with infective larvae is a key preventative measure that can be achieved to a large extent with adequate management measures. Rotational grazing with a change interval of 4 days and keeping the paddocks empty for at least 40 days significantly reduces pasture contamination. This is due to the fact that larvae are susceptible to dryness and won't survive more than 4 or 5 weeks on pasture if they do not find an adequate host. Obviously, by very moist weather or where pastures are almost permanently moist survival may be longer. Alternate grazing with sheep and/or horses may be considered, since Dictyocaulus species are quite host-specific (for cattle, sheep & goats, horses). The longer the absence of the specific host, the higher will be the reduction of its specific lungworm. However, this may not be advisable in places infected with gastrointestinal roundworms that are simultaneously parasitic of cattle and sheep or horses. For their first grazing season it is highly advisable that young stock does not share the pastures with older stock that has been exposed earlier to infected grounds and can therefore shed larvae. It must also be avoided that young stock uses pastures already used by older stock during the same season. It must also be considered that heavy rains and flooding can disseminate infective larvae inside a property or from one property to neighboring ones. Keeping the pastures as dry as possible and keeping livestock away from places excessively humid are additional key measures to reduce the exposure of livestock to infective larvae. In endemic regions preventative strategic treatment of young stock is often recommended just prior to their first grazing season, followed by additional treatments depending on the infestation level of the pastures and the residual effect of the administered anthelmintic (Junquera, 2014). c) Economic Impact of the Disease

The vitality and wellbeing of horses of all age are thread by a variety of internal parasites and the use of control ensures and the best performance (Power, 1992). Internal parasites are one of the greatest limiting factors to successful horse rising throughout the world. All horses at pasture become infected and suffer a wide range of harmful effects ranging from impaired development and performance to death despite the availability of large array of modern anthelmintic, parasite controls often fail to safeguard horse health.

The main reason for these break downs are errors the choice of anthelmintic and in the time of treatment (Herd, 1987).

12. d) Prevalence of lungworm infection in different parts of Ethiopia

The concern of lungworm in Ethiopia is increasing and is now to be a major problem of equine in the central highlands of Ethiopia. However there were little preliminary findings of lungworm infection which were done by few researchers of the country (Table 2).

| Macrolides | Ivermectin | 0.05 | PO and SC |

| Benzimidazole Oxfendazole | 2.5 | PO | |

| Fenbendazole | 5.0 | PO | |

| Albendazole | 7.5 | PO | |

| Febantele | 10 | PO | |

| Imidathiazole | Levamisole | 8.0 | PO |

| Source: Blood et al. (2000) | |||

| Volume XVII Issue II Version I | |||

| D D D D ) G | |||

| ( | |||

| Medical Research | |||

| Global Journal of | S. No -2 4 5 | Site of study North Wollo Jimma South eastern Ethiopia | Prevalence in % Researcher name 17.5 Belay, 2005 13.8 Tihitna et al., 2012 42.7 Kamil et al. (2017) |

| V. Conclusion | |||