1. Introduction

ral health related quality of life (OHRQoL) is a relatively new but rapidly growing phenomenon 1 that appeared in the literature in the early 1980s. 2 Its dimensions include areas of concern to individual other things reflects on people's comfort while eating, sleeping, as well as the effect of oral health on social The working lives of HCW like doctors and nurses is associated with a high level of work-related stress and these HCWs often do not pay a sufficient both physical and psychological ill health was identified among HCW in the UK. 21 The literature focusing on the OHRQoL of healthcare personnel is scarce. It is important to understand healthcare personnel's O patients. 3 It is therefore multidimensional and among amount of attention to their own health. 20 High levels of interactions and self-esteem in everyday life. 4, 5 Slade 6 and others 7,8 identified the shift in the perception of health from merely the absence of disease and infirmity to complete physical, mental and social well-being, from the definition of health given by the World Health Organization (WHO), 9 as the key issue in the conception of health related Quality of life (HRQoL) and, subsequently OHRQoL.This definition of health by the WHO thus included quality of life (QoL) within the broader definition of health 10 unlike the biomedical model. Consequently, any measure of health needs to assess social and emotional aspects of health as well as assessing presence or absence of disease. 11 Until recently, the psycho-social consequences of oral conditions have received little attention. Also, the oral cavity has historically been dissociated from the rest of the body when considering general health status. It is however established that oral health is an integral part of general health and is one of the determinants of quality of life. 7 Thus the need to conceptualize oral health as an integral part of overall health and to consider its contribution to overall health related quality of life (HRQoL) has been stressed. 12 This is supported by recent research which highlighted that oral disorders have emotional and psycho-social consequences as serious as other disorders. 11,13 Furthermore, Reisine 14 and Gift et al 15 indicated that approximately 160 million work hours a year are lost due to oral disorders. With the growing interest in the QoL, several studies have been conducted to assess QoL among working adults in different occupations. [16][17][18][19] Most of these research has primarily focused on HRQoL, the quality of work life (QWL), and effort-reward imbalance. There is paucity of data on the impact of oral health on QoL among workers and especially among healthcare workers (HCW). revealed that the characteristics and explore their pattern of clinic attendance due to oral health problems and how these impact on their daily lives. This will optimize the use of support and interventional measures and help to reduce negative effects on their lives. Minimizing the burden on healthcare personnel will possibly improve the quality of life and medical outcomes of their patients and the relationships with their private life. Based on: the importance of oral health to psychological well-being; the paucity of data on the impact of oral health on QoL among populations in sub-Saharan Africa and in Nigeria; and the lack of data on OHRQoL among HCWs in Nigeria, this study aimed to determine the OHRQoL among doctors and nurses; explore the association between the OHRQoL and the use of dental services by the HCWs in a teaching hospital in Nigeria.

2. II.

3. Materials and Methods

4. a) Study design and data collection

This study was conducted as a cross-sectional study assessing the OHRQoL of HCW at the University of Maiduguri Teaching Hospital, Maiduguri, in northeastern Nigeria. The approval for the study was granted by the Research and Ethics Committee of the hospital before commencement. The study population comprised of all doctors and nurses in the various hospital departments that agreed to participate in the study. Thus a total population survey was carried out, but excluded doctors and nurses who were on leave from work during the study as well as doctors sent out for clinical rotations to other hospitals. Consent was sought from each participant following an explanation of the study objectives, procedure for the collection of data, the benefits of the research, and the confidentiality of the data collected. A copy of the self-administered questionnaire was given to each participant and retrieved after completion at the end of the working day. The survey used a short demographic questionnaire constructed to collect information such as the participant's gender, age, profession, and dental visits. The remaining part of the questionnaire contained the short form of the oral health impact profile (OHIP-14) used to collect information on oral health impact on QoL.

The OHIP-14 is one of the OHRQoL instruments that have been widely used in several cross-sectional and longitudinal studies. 19,20 It consists of self-reported measurements of the adverse impacts of oral conditions into seven domains namely functional limitation, physical pain, psychological discomfort, physical disability, psychological disability, social disability and handicap. Each domain has two questions.The responses to these questions are to be scored on a 5point Likert scale: 0, 1, 2, 3, and 4 for "never", "hardly ever", "occasionally", "fairly often", and "very often" respectively. A more negative impact of oral health on the person's life is indicated by the answers "fairly often" and "very often". One response per question reveals how often the impact is felt in the last one year. The questions have already been pre-weighed to reflect population judgments about the relative unpleasantness of each impact. 22 The coded responses are multiplied by their weights and the sum of the products within each domain represents subscale scores, and summation of the subscale scores will produce an overall OHIP-14 score for each participant. Subscale scores for each domain and an overall OHIP-14 score range from 0 to 4 for the subscales and 0 to 28 for the overall OHIP-14 score for the participant. A high score represents a greater impact and thus a low OHRQoL, and a low score represents a lesser impact and a higher OHRQoL.

5. b) Data Analysis

Analysis of the data obtained was performed using Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS) for III. A total of 250 questionnaires were distributed and 236 were completed and returned, a response rate of 94.4%. Their ages ranged between 20 and 58 years with mean age of 33.1 ± 7.1. The age range 25 -34 accounted for the majority of the study population. (Table 1) One hundred and sixty six of the participants had visited the dentist at least once, 79 (47.6%) of which had been in the last one year. Majority of the participants visited the dentist for check-up and/or prophylaxis. No significant difference was seen between the genders, professions and among the age groups for visit to the dentist (p= 0.19). on daily life. 20 The questionnaire has 14 items organized a) The Prevalence of Impact

6. Results

7. Volume XVII Issue VII Version I

The prevalence of impact of oral health on the subjects is expressed as the percentage of the participants that responded with "very often" or "fairly b) Severity of Impact

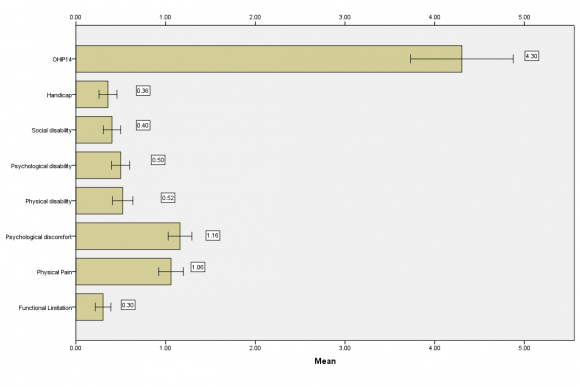

The severity of impact calculated as the mean value of the responses to the OHIP-14 items in the domains and overall was lowest in the functional limitation domain (0.30±0.04(S.E.M)) and highest in the psychological discomfort domain (1.16±0.07(S.E.M)) [Figure 1]. No statistical significant difference between the genders in all the domains and overall OHIP scores p>0.05, except in the social disability domain ("Have you been a bit irritable with other people because of the problem with your teeth or mouth? And "Have you had difficulty doing your usual jobs because of the problem with your teeth?"), where the females expressed a higher severity of impact (p = 0.04) [Table 3]. often" to all the items in the OHIP-14 questionnaire.

Table 2 shows the percentage of participants that responded with "very often" or "fairly often" to all items in each domain and to all the items in the OHIP-14 questionnaire, expressed as a percentage of the total number of respondents. The highest prevalence of impact (27.9%) was noted in the physical pain domain with item number 4, "Have you found it uncomfortable to eat any foods because of the problem with your teeth or mouth?" The 18 -24 years age group reported higher impact in all the domains and overall OHIP-14 except in the psychological discomfort domain. These differences were not statistically significant (Table 4). domains. Comparison of the severity scores based on reason for clinic attendance showed that participants who visited the dentist for emergency reasons had a significantly higher OHIP-14 score (p <0.05) (Table 5) and domain scores except in the functional limitation domain (p=0.30). Post hoc analysis (Bonferoni) revealed the significant differences to be due to differences in the severity scores for check-up versus emergency visits in all domains and overall OHIP (p=0.00) and the OHIP-14 scores between check-up and routine visit scores (p=0.01). There was no significant difference in domain and overall OHIP-14 scores between routine and emergency visits (p=0.48), as well as between checkup and routine scores in the psychological disability (p=0.12), social disability (p=0.40) and handicap (p=1.00) domains. A multiple regression analysis was run to evaluate the relationship between the OHIP-14 score and the variables, age, gender, profession, prior visit to the dentist and reason for last visit. These variables were statistically significantly related to the variations in the OHIP-14 score, F (5, 230) = 10.542, p = .000 (i.e. < .005), R 2 = .186, R = .432 and adjusted R 2 = .169. Where F is the test of fit of the regression model, 5 and 230 are the degrees of freedom for the regression and residual models. R-squared gives the percentage of explained variation in the OHIP-14 scores assuming all variables in the model affect it, and the adjusted R-squared gives the percentage of variation explained by only those independent variables that in reality affect the OHIP-14 score. In this regression model, however, only age, prior visit to the dentist and reason for last visit added statistically significantly to the prediction of OHIP-14 score, p < .05 (Table 6).

The nurses had significantly higher domain scores in the functional limitation (0.40±0.07, p=0.01) and handicap domains (0.47±0.08, p=0.01). They also reported higher overall impact scores though not significant (4.58±0.43, p=0.28).

The participants who had visited the dentist at least once in the past had significantly higher overall OHIP-14 severity of impact score when compared to those who had never been to the dentist (Table 5). This trend was noted in all the domain scores except in the functional limitation (p=0.43) and handicap (p=0.33)

8. Discussion

A relatively small proportion of the participants had their daily life affected negatively by the oral conditions that they suffer from as seen from the reported prevalence of impact (13.2%) in this study. The interpretation of this is that the frequency of the impact of oral disorders on the daily lives of these proportion of the participants is higher than in the rest of the participants. Within the domains, items 2, 3, 4 and 5 in the functional limitation (item 2), physical pain (items 3 and 4) and psychological discomfort (item 5) domains had the most prevalent impacts on QoL. The highest, as expected, is item 4 since it reflects level of comfort while eating. This is expected since the most common oral disorder still remain dental caries and its sequelae and periodontal disease, both of which would result in pain while eating. It would have been enlightening to compare these prevalence values to that of the general population but for lack of such data. However, a study of OHRQoL among patients with dentine hypersensitivity in Nigeria also reported the highest prevalence of impact (64.7%) on QoL with item 4. 23 Pain from oral disorders while eating or drinking therefore appears to have a major effect on QoL. This stand was corroborated again by the calculated mean value of the responses to the items of the OHIP-14, that is, the severity of impact, where the physical pain domain mean score was second only to that of the psychological domain.

In conjunction, both the prevalence and severity of impact showed that oral disorders among the participants did have an impact on their QoL. The severity of impact was noted to be highest in the domain of psychological discomfort followed by physical pain as is also seen for the domain scores for both genders in the study. This is consistent with results reported by OHIP-14 score was however lower than that reported in other studies: 4.55 among Technical Administrative Workers in Portugal; 26 9.60 among healthy Spanish workers; 27 and 12.0 among dental patients in Ibadan, Nigeria. 28 It is important to stress that these comparisons should be interpreted with caution as differences in perception of impact among populations depends on several factors. The perception of QoL itself is highly subjective, therefore individual perceptions vary with social, cultural, and political conditions. 29 The values reported therefore make meaning to the individuals in the setting where the study was conducted. However, the low severity of impact for the HCWs in this study may still be explained by their high level of education, and probably awareness of oral health. Similarly, Mesquita and Vieira 30 reported lower impact of oral health on QoL among subjects with higher income and education and suggested that this may be due to higher income and information about oral health and dental services.

Concerning the association between sociodemographic variables among the participants and OHRQoL, age and gender had minimal influence. This is Batista et al. 25 for age range and gender respectively.

Although minimal, the influence of age was seen as a higher impact of oral disorders on QoL in all the domains and overall OHIP-14 score except the psychological domain among the younger age groups. In contrast, a greater impact was reported among older individuals by Guerra et al. 26 and Mesquita and Vieira. 30 The female HCWs in this study only had a significantly greater severity of impact on their daily social life as seen from their score in the social disability domain, but not in the mean OHIP-14 score. The reason for this finding is unknown, but may be due to differing subjective perceptions of social demands between the genders. It may also not be unrelated to the female gender having an emotion-focused approach to coping with health problems. 32 This may therefore explain why they may be a bit irritable with other people as well as having difficulty doing their usual jobs because of the oral disorders. Greater impact in females, that is, lower OHRQoL, has also been reported in other studies. 25,30,33 Participants with a history of use of dental care facilities reported significantly lower OHRQoL. It is known that pain is the most frequent reason why adults visit the dental clinic, resulting in attendance that is sporadic and spurred by onset and persistence of symptoms. 34,35 This was supported by the results of this study by the significantly greater severity of impact reported by those who visited the dentist for emergency reasons when compared to routine visits and check-up. Emergency reasons here refers primarily to visits due to pain and discomfort such as endodontic emergencies Locker and Quinonez 24 and Batista et al. 25 The mean and trauma. This is consistent with reports on the association between reason for dental appointment and significance of impact from other studies. 25,26,30,31 V.

9. Conclusion

The present study revealed that the impact of oral disorders on the OHRQoL among the HCW was relatively low. All the variables and factors included can however be used as predictors of this impact. Physical pain, functional limitation and psychological discomfort were the most prevalent impacts while psychological discomfort was reported as the most severe impact. The various factors assessed in this study influenced the perception of OHRQoL. Being female, being younger in age, a nursing staff, and having attended a dental clinic for treatment and attendance due to emergency reasons were associated with poorer OHRQoL. Based on the results of multiple regression analysis, all five variables considered in the study added statistically significantly to the prediction of the participants OHIP-14 score and hence their OHRQoL. However, these variables could only account for 16.9% of the variations of the OHIP-14 scores. This mean that there are other factors which may be responsible for the remaining variations. As suggested by Turrel et al., 29 these unexplained variations in the perception of QoL among populations may be due to social, cultural and political differences.

| among the participants | |

| Variable | Frequency (%) |

| Age group | |

| 18 -24 | 27 (11.4) |

| 25 -34 | 143 (60.6) |

| >35 | 66 (28.0) |

| Gender | |

| Male | 130 (55.1) |

| Female | 106 (44.9) |

| Profession | |

| Doctors | 107 (45.3) |

| Nurses | 129 (54.7) |

| Prior dental visit | |

| Yes | 166 (70.3) |

| No | 70 (29.7) |

| Total | 236 (100.0) |

| Reason for dental visit | |

| Check-up/prophylaxis | 96 (57.8) |

| Routine treatment/review | 46 (27.7) |

| Emergency treatment | 24 (14.5) |

| Total | 166 (100.0) |

| Domains | Items |

| Year 2017 | |||||

| Volume XVII Issue VII Version I | Domain (N = 236) | Mean scores ± SEM Male Female | t | p | |

| D D D D ) | Functional Limitation | 0.28±0.05 | 0.33±0.07 | -0.47 | 0.64 |

| ( | Physical Pain | 1.11±0.09 | 0.99±0.11 | 0.84 | 0.40 |

| Psychological Discomfort | 1.15±0.08 | 1.17±0.11 | -0.11 | 0.91 | |

| Physical Disability | 0.46±0.07 | 0.59±0.10 | -1.09 | 0.28 | |

| Psychological Disability | 0.45±0.06 | 0.56±0.09 | -0.98 | 0.33 | |

| Social Disability | 0.31±0.05 | 0.52±0.09 | -2.09 | 0.04 | |

| Handicap | 0.27±0.05 | 0.47±0.09 | -1.96 | 0.05 | |

| OHIP-14 | 4.04±0.31 | 4.63±0.52 | -0.97 | 0.33 | |

| attendance and reason for attendance | |||

| Variable | Mean score ± S.E.M. | t | p |

| Dental clinic attendance | |||

| Yes | 4.04±0.31 | -2.74 | 0.01 |

| No | 4.63±0.52 | ||

| Reason for clinic attendance | F | p | |

| Check-up/prophylaxis | 3.42±0.31 | ||

| Routine treatment/review | 5.77±0.80 | 13.81 0.00 | |

| Emergency treatment | 8.55±1.19 | ||

| Domain (N = 236) | 18 -24 | Mean score ± S.E.M. 25 -34 | 35 -44 | F | p | ||

| Functional Limitation | 0.59±0.17 | 0.25±0.05 | 0.30±0.10 | 2.98 | 0.05 | ||

| Physical Pain | 1.36±0.23 | 1.00±0.08 | 1.08±0.14 | 1.31 | 0.27 | ||

| Psychological Discomfort | 1.11±0.26 | 1.24±0.09 | 1.00±0.12 | 1.29 | 0.28 | ||

| Physical Disability | 0.70±0.17 | 0.48±0.07 | 0.54±0.12 | 0.75 | 0.48 | ||

| Psychological Disability | 0.73±0.19 | 0.51 ±0.06 | 0.38±0.09 | 2.02 | 0.14 | ||

| Social Disability | 0.64±0.20 | 0.39±0.06 | 0.33±0.09 | 1.71 | 0.18 | ||

| Handicap | 0.65±0.22 | 0.30±0.06 | 0.36±0.09 | 2.36 | 0.10 | ||

| OHIP-14 | 5.80±1.03 | 4.17±0.35 | 3.98±0.57 | 1.76 | 0.18 | ||

| Variables | Unstandardized Coefficients B Std. Error | Standardized Coefficients Beta | t | Sig. | |

| (Constant) | -4.308 | 1.480 | -2.911 | .004 | |

| Gender | .712 | .547 | .079 | 1.301 | .194 |

| Age | -1.142 | .451 | -.155 | -2.531 | .012* |

| Profession | .295 | .550 | .033 | .536 | .592 |

| Visit to the dentist | 8.508 | 1.226 | .873 | 6.938 | .000* |

| Reason for last visit | 2.699 | .445 | .770 | 6.065 | .000* |

| *p < 0.05 | |||||

| IV. | |||||