1. Introduction

omestic violence against women is as a significant social as well as public health problem. Nurses are a large group of service providers having a central moral of caring in health promotion through their work to improve the health status of communities. As a group of health workers, female nurses who are married traditionally have been insecure to consider domestic violence as a health issue. They have also been reluctant to deliberate this issue in hospital settings. Besides this, female nurses have an essential role to play in their work in hospital and community levels and to assist women and their children who are victims of violence in a domestic situation. Limited studies are available on the prevalence of domestic violence against them globally [1]. The nature of duty and work schedules of nurses are unique that can have different implications for their family life. As there is a high level of role conflicts and significant level of occupational stress, nurses have been recipients of abuse or witness abuse either at home or workplace. Arends et al. [2] found that statistical evidence on domestic violence against female nurses showed that, knowledge about the characteristic of violence and its effects were almost absent among them. The term 'Domestic Violence' refers to physical, verbal, psychological, sexual, or economic abuse (e.g., withholding money, lying about assets) in a domestic setting used to exert power or control over someone or to prevent someone from making a free choice. This includes any behaviors like intimidate, manipulate, humiliate, isolate, frighten, terrorize, coerce, threaten, blame, hurt, injure, or wound someone. Rape, incest, and dating violence are all considered to be forms of domestic violence in Fedovskiy et al. [3]. There are four main types of domestic violence (also called intimate partner violence):

? Physical ? Sexual ? Psychological ? Economical [4]Brown et al. [5] shows that nurses have to play a significant role in the prevention and early intervention of domestic violence. Florence [6] describes in a recent review of international literature on abuse or violence identified that female nurses who have been assaulted by their partner mostly have worse health than other women. They may also appear nervous, ashamed, or evasive. They cannot concentrate on their work and duties might be hampered or sometimes disgraced on by patients and colleagues. Costa et al. [7] shows maintaining peace and harmony, caring for children while protecting them from the impact of the abuse or violence, as well as living with the fear of precarious personal safety. Campbel [8] proves that many women do not want to end their relationship, but they however, want the violence to stop. Nurses should ensure their ways of improving their self-esteem and the health status of nurses of all communities.

In Bangladesh, violence against married female nurses is a very common practice. It leads to inequality in the distribution of power, deprivation of their equal opportunity of work and decision making. Martin et al. [9] shows that nurses can suffer from various types of domestic violence in their lives. Although domestic violence was usually done by husband, children, and in-laws also committed different types of violence. Vacherc et al. [10] presents that domestic violence has direct consequences for their physical, mental, sexual and reproductive health of nurses as well as economic cost which effect the psychological development of children. To fight against this violence, strict laws can implement. Kaur et al. [11] proves that multisectoral organizations can also take necessary steps to prevent domestic violence. Kumar et al. [12] shows that a coordinated effort for practical and different interventions can be invented to eradicate violence against female nurses to achieve their equality and selfdignity. To achieve success in this regard, legislation and developed policies may able to focus on the discrimination against female nurses and thus may promote gender equality, support, and help to move towards more peaceful cultural norms. We included those female nurses informationthat provided written consent and exclude those who were ill or absent from their work. We used appropriate type of non-probability sampling and the nurses fulfilling the above mentioned criteria were selected for the interview. A semi-structured questionnaire developed for collection of required information. Before collection data, pre-testing of questionnaire was done in Sir Salimullah Medical College and Mitford Hospital. Data were collected by woman to woman interview of respondents by the researcher. Before data collection, informed written consent was taken from the nurses. They were informed clearly about the objective of the study. The interview conducted in Bangla. Data processing involved categorization of the data, coding, summarization the data, categorization to detect errors to maintain consistency and validity. After collection, data checked, verified, compiled and analyzed by SPSS (Statistical Package for Social Science) software version 22. Prior authorization was taken from the Institutional Ethical Committee (IEC) of Sir Salimullah Medical College and Mitford Hospital, Dhaka, Bangladesh. Administrative permission was taken from the respective hospitals. All nurses were informed verbally about the study design and the objective. A written consent form was obtained from each subject. No medical surgical or therapeutic intervention was applied. There was no involvement of physical and social risks. All the records were kept under lock and key. Every respondent had the opportunity to receive or refuse participation.

2. II.

3. Materials and Methods

4. III.

5. Results

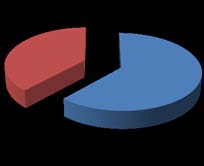

Table 1 shows that out of 192 nurses, around 44.3% were between 31 to 40 years of age and second highest (37.4%) percentage were between 41 to 50 years. About 9.9 % were between 51 to 60 years and only 8.3% were between 21 to 30 years. Figure 1 shows that the majority of the nurses were Muslims (71.4%) followed by 24.5% were Hindus and only 4.2% of them were Christians.

6. Fig. 2: Distribution of nurses by education

Average monthly incomes of the nurses were Tk. 30729.6. Among them, the majority (30.2%) had a monthly income between Tk. 10001-20000; while about 25.5% had between Tk. 20001-30000 and lowest (9.4%) number of nurses had a monthly income between Tk. 50000-70000 as shown in Table 2. Table 3 depicts that according to monthly family income of nurses, the average monthly family income was Tk. 50130.7 and the highest (53.6%) number of them had between Tk. 50001-70000. Approximately 21.9% had between Tk. 30000-40000 and only 3.6% had between Tk. 20001-30000. 4 illustrates that according to the educational status of the husband, around (44.3%) percentage were graduated followed by 30.7% completed HSC or equivalent class. About 18.2% were post-graduated and only 6.3% and 0.5% studied SSC or equivalent level and others respectively. Table 5 demonstrated that according to the occupational status of the husband, around 46.4% were businessmen, while 29.7% were non-Government service holder. About 15.1% were paramedics and only 3.6% and 2.6% were doctors and Government service holders respectively. The average monthly income of husbands was Tk. 27086.44 and majority (43.2%) of them had between Tk. 20001-30000. About 31.3% had 30001-50000 and very few (0.5%) of them had a monthly income between Tk. 1001-10000 as shown in Table 6. From figure 3, it is estimated that among 192 female nurses, most (72%) of them were both, the main earning member of the family. About 19.0% were self and only 9.0% were husbands who were the main earning members in the family. Table 7 shows that greater (65.6%) number of victim nurses were Muslims. Approximately 27.9% of victims were among Hindu nurses and only 6.6% were among Christian nurses. Though the evidence of violence was more among Muslim female nurses, there was no statistical association between religion and victim of domestic violence in this study (as P>0.05). Table 9 shows that about the educational status of the husband, those who studied HSC or equivalent level created more (41.0%) domestic violence; while among graduated about 31.1% were victims of DV. But among SSC or equivalent level of the educational status, it was much less (13.1%) and there was a strong association between the education of husband and domestic violence (P<0.01).

Table 10 describes between Tk. 20001-30000 monthly incomes of nurses, the highest (42.6%) number of victims were present followed by approximately 34.4% of victims had between Tk. 10001 -20000. Only 4.9% of victims had between Tk. 50001 -70000 and there was a very highly significant relation between monthly income of nurses and DV (P<0.005). Table 11 mentions that bythe monthly income of the husband, those who had between Tk. 20001 -30000 created more (44.3%) domestic violence, followed by 37.7% of victims had between Tk. 10001-20000. Only 11% of victims had between Tk. 30001 -50000 and DV were almost absent (0.0%) between Tk. 1001-10000 monthly income group. There was high statistical significance between the income of husband and domestic violence as p<0.05 Table 12 estimates that domestic violence was more (39.3%) prevalent among those who had a monthly income between Tk. 50001 -700000, while it was lowest (9.8%) those had between Tk. 20001 -30000 and the second highest (27.9%) number of victims were present between Tk. 40001 -50000 income group. There was a strong association between monthly incomes of the families and victim of DV as p<0.05. Table 13 illustrates that greater number (82.0%) of domestic violence was present among those nurses who were both, the earning member of the family, while it was lowest (6.6%) among them whose husbands were the main earning member of the family. There was no significant association between the earning member of the family and victim of domestic violence (p>0.05) in this study. Table 14 shows that according to the family member of nurses, the majority (71.0%) of them had 6-8 and only 12.9% had 9-11 family members. Figure 4, the pie chart describes that among 192 married female nurses, 32% was the victim of domestic violence while about 68% had no evidence of domestic violence. Figure 5 demonstrates that among 32% victim married female nurses, around 22.4% suffered from mental violence, about 6.8% physical, 2.1% sexual and only 0.5% tolerated economic violence.

7. Fig. 5: Distribution of nurse victim of DV

Table 15 shows that nurse who suffered from physical violence, the most common type was beating (69.2%) and another common type of physical violence was slapping (30.8%) by their husbands. The most common (30.8%) reason for physical abuse was related to appearance, followed by about 23.1% were related to their children and only 7.7 % were related to dowry as shown in Table 16. Figure 6 shows that greater (62%) number had moderate and around 38% had a severe impact health of married female nurses due to physical violence. 17 depicts that the most common (31.7%) type of mental violence was using abusive language and another common (25.0%) type was created pressure doing things they didn't like. About 8.3% was stopping talking and only 5.0% was another type of mental violence they experienced. Table 19 shows that majority (66.7%) had the reason of sexual violence was promiscuity of the husband, while about 22.2% were victims by forceful intercourse and around 11.1% were had having suspicious behavior of the husband on working women. Table 20 shows that a large (74.6%) number of domestic violence was created by their husbands while about 22% were created by their mothers -in law and only 3.4% were victims by their fathers-in-law. Among those who had received treatment, only 3.6% took psychiatric treatment or medicine and 2.6% received psychiatric counseling for their mental trauma shown in table 22. IV.

8. Discussion

This descriptive type of cross-sectional study was carried out in Government and private hospitals in different areas of Dhaka city. The purpose of this study was to assess the pattern and reasons responsible for domestic violence against married female nurses.

This study revealed that out of 192 nurses, about 44.3% were in 31-40 years of age and the second-highest (37.5%) number of nurses was between 41-50 years of age. Only 9.9 % were between 51-60 years and the lowest percentage (8.3%) were between 21-30 years of age. Sharma et al. [13] shown that majority 41.58% of victim nurses were between 30-40 years followed by 22% were between 21-30 years and lowest number only (2%) were between 51-60 years of age.

Most (71.4%) of the nurses were Muslims, followed by 24.5% nurses were Hindus and only 4.2% of them were Christians. About DV, most (65.6%) of victim nurses were Muslims followed by 27.9% were Hindus, estimated in this study. According to Rao [14], DV was more prevalent among Muslims (80%); while about 65% were among Hindus and the lowest numbers only 5% were among Christian nurses.

This study illustrated that the majority (45.8%) of nurses studied up to SSC or equivalent level followed by 40.1% had passed HSC or equivalent level. Only 7.8% and 6.3% were graduated and post-graduated respectively in this study. In compliance with domestic violence, the prevalence was highest (42.6%) among female nurses those had passed HSC or equivalent level. Around 42.6% of victims were having SSC or equivalent level of education and the lowest numbers only (3.3%) were among post graduated. There was no statistical significance (p= 0.461) between the education of nurses and DV in this study. In agreement with this present study findings, Kidwai [15] reported that nurses completed only HSC or equivalent level suffered the highest level of DV but it was lower (5.2%) among post-graduated and there was a strong association (P=0.005) between the educational status of nurses and domestic violence.

On the other hand, according to the educational status of the husband, the present study also estimated that around 44.3% were graduated followed by 30.7% were having HSC or equivalent level. About 18.2% were post-graduated and only 6.3% studied SSC or equivalent level of education. Husbands studied HSC or equivalent level, the highest (41.0%) rate of domestic violence was created by them and the graduated husbands ranked second highest (31.1%) in creating DV. There was a strong association (p=0.002) between the education of husbands and DV. In this respect Vachercet al. [10] emphasized that husbands those who had passed HSC or equivalent level of education produced more (59%) DV.

This study depicted that there was a very highly significant relation between monthly income of nurses and victim of domestic violence. This study demonstrated that DV was lower in the higher monthly income group of nurses. Moreover, Campbell [8] reported that DV was widely prevalent among those nurses having a monthly income between Tk. 15000-30000 and there was a highly significant relation (p=0.001) between monthly income and domestic violence.

The current study identified that the majority (46.4%) of them were a businessman. Sambisaet al. [16] shown that majority (65.5%) husbands of nurses were businessmen and the husbands those did service in private sectors created more (45.3%) domestic violence. The majority (43.2%) of them had income between Tk. 20001-30000 and the largest (44.3%) numbers of perpetrators were among this income group. In this regard, Willson [17] stated that DV was more prevalent among the nurses whose husband had a monthly income between Tk. 25000-30000. Campbell [8] predicted that, the husbands of nurses having a monthly income between Tk. 20000-40000 created the highest range of domestic violence.

This study estimated that among 192 nurses most (72.0%) of them were the both, the earning members in their families and DV was also frequent (82.0%). There was no statistical association between earning member of family and DV in this study as p=0.103. But Khan et al. [18] predicted that domestic violence more prevalent among them; those husbands were the main earning member of the family.

Most (49.2%) of victim nurses were between 21 -25 years of age at the time of marriage. However, there was no significant (p=0.196) relation between victim of DV and age of the nurses at the time of marriage. According to Sayem et al. [19], they demonstrated that the occurrence DV was higher between 20-30 years of age and there was a strong (0.001) association between age at the time of marriage and found, most of them (96.7%) the victim of DV getting marriage arranged by their families. Another study Ahmed et al. [20] revealed that DV was widely prevalent (85.0%) among nurses who had got married arranged by their families.

This study identified that majority (95.3%) of them had their first marriage and the most common reason for getting re-marriage was physical torture (55.6%) by their husbands. Approximately (22.2%) were due to dowry and 11.1% were due to widowed and being a job holder.

This study showed that the majority belongs to nuclear family and the prevalence was highest (86.9%) among them. In agreement with this Baral et al. [21] demonstrated a significant relationship between types of family and their exposure to DV.

The current study identified that most (81.0%) of female nurses had one or two children and only 0.6% had 5 or 6 children. Another study Schular et al. [22] illustrated that nurses having 5-6 children experienced more (52.2%) DV in their lives.

This study illustrated that 32% were the victim of DV, among them, 22.4% suffered from mental violence, 6.8% physical, 2.1% sexual and only 0.5% economic violence. Meanwhile, Vacherc et al. [10] revealed that majority (49.0%) of female nurses suffered from mental violence and 15% experienced economic violence.

A notable number (69.2%) were beaten by their husbands and the most common reason was related to appearance (30.8%), (23.1%) due to their children. The most common type of physical torture was beating (65.0%) and slapping (43.0%). Trevillion et al. [23] reported in a study of DV in Minia, Egypt. Dowry was another main cause of physical violence against female nurses in India which is focused in Ali et al. [24].

53.8% of nurses did not receive any type of treatment; while about (46.2%) had taken. Cope et al. [25] reported that most (68.0%) of nurses did not receive any treatment as a result of DV and especially physical violence caused serious impact on their reproductive health as well as overall wellbeing.

31.35% experienced mental violence and the most common reason was using abusive language (31.7%) by their husbands. Another important cause was creating pressure to do things they didn't like (25.0%). On the same line, a study on nursing students in Australia Doran et al. [26] stated that using abusive language was one of the most common.

Only 4.7% of nurses had experienced sexual violence and the majority (66.7%) of them had the reason for the promiscuity of husbands. Also about 22.2% were abused by forceful intercourse by their husbands and minor (11.1%) were the cause of suspicious behavior of husbands on working women, as reported in this study. In another study Woods [27] represented that major (35%) cause of sexual violence experienced by nurses was promiscuity of husbands.

The current study also depicted that DV was mainly created by their husbands (74.6%). The main perpetrators of violence were their husbands (85%) and about (64%) were mothers-in-law in Khan et al. [18].

58.2% had taken preventive steps among victim nurses. The most common (41.5%) approaches were negotiation and seeking family help while restoring to legal actions was much less (2.4%) according to this report. Moreover, Kalokhe et al., [28] mentioned that majority (56.0%) of victim nurses tried to solve their problems by discussing with the members in their laws' families. In another study, Florence [6] illustrated that nurses working in private sectors were more vulnerable to DV due to their financial incapability and only 5.0% seek help from NGOs Meanwhile, Kader [29] in Malaysia demonstrated that none of the female nurses exposed to DV in Malaysia took a legal step in Malaysia in Malaysia.

This study was shown that only 6.3% received treatment for mental trauma. Few of them received psychiatric treatment (3.6 %) and psychological counseling (2.6%). Only (5.0%) took treatment for mental illness and among them, only 2% received psychological counseling. A similar finding was reported in a study of DV in Bangladesh in Khan et al. [18].

This study also described that about 33.3% tried to make them mentally strong as cope with violence. In another study Sayem et al. [30] revealed that nurses victim of DV tried to make them financially (45.0%) and mentally (34.0%) strong so that they could cope the violence easily.

From the above discussion, it was revealed that according to religion, status of nurses, type of family, ways of marriages, age at the time of marriage, main earning member of the family, there was no significant relation with domestic violence. But on the basis of the education of husband, incomes of nurses, their husband, and total family income, there was a very strong and notable association with domestic violence.

V.

9. Conclusion

Domestic violence against female nurses is one of the burning issues in contemporary Bangladesh. Women, working as nurses in Bangladesh, have many limitations to expose the violence against them. The bindings of cultural norms and values trigger the violence against Though protection act 2010 was being implemented at the local level rigorously designed research was also needed to develop and make a coordinative intervention with victim and perpetrator. Attention should be needed on government and as well as non-Government nurses by the government and other NGOs.

| n= | ?? 2 ???? ? ?? 2 |

| Age (years) | Frequency | Percent |

| 21-30 | 16 | 8.3 |

| 31-40 | 85 | 44.3 |

| 41-50 | 72 | 37.5 |

| 51-60 | 19 | 9.9 |

| Total | 192 | 100.0 |

| Statistics | Mean ± SD (40.98 ±7.232) years | |

| Income (Tk.) | Frequency | Percent |

| 10001-20000 | 58 | 30.2 |

| 20001-30000 | 49 | 25.5 |

| 30001-40000 | 29 | 15.1 |

| 40001-50000 | 38 | 19.8 |

| 50001-70000 | 18 | 9.4 |

| Total | 192 | 100.0 |

| Statistics | Mean ± SD (30729.66±8434.37) | |

| Income (Tk.) | Frequency | Percent |

| 20001-30000 | 07 | 3.6 |

| 30001-40000 | 42 | 21.9 |

| 40001-50000 | 40 | 20.8 |

| 50001-70000 | 103 | 53.6 |

| Total | 192 | 100 |

| Statistics | Mean ± SD | |

| Table | ||

| Education | Frequency | Percent |

| SSC or equivalent | 12 | 6.3 |

| HSC or equivalent | 59 | 30.7 |

| Graduate | 85 | 44.3 |

| Post graduate | 35 | 18.2 |

| Others | 1 | 0.5 |

| Total | 192 | 100.0 |

| Occupation | Frequency | Percent |

| Doctor | 5 | 2.6 |

| Government service | 5 | 2.6 |

| Non-Government | 57 | 29.7 |

| Paramedics | 29 | 15.1 |

| Business person | 89 | 46.4 |

| Others | 7 | 3.6 |

| Total | 192 | 100.0 |

| Income (Tk.) | Frequency | Percent |

| 1001-10000 | 1 | 0.5 |

| 10001-20000 | 48 | 25.0 |

| 20001-30000 | 83 | 43.2 |

| 30001-50000 | 60 | 31.3 |

| Total | 192 | 100.0 |

| Statistics | Mean ± SD = 27086.44±2024.9 | |

| Victim of Domestic | ||||

| Religion | Violence | Total | Significance | |

| Yes | No | |||

| Muslim | 40 65.6% | 97 74.0% | 137 71.4% | |

| Hindu | 17 27.9% | 30 22.9% | 47 24.5% | X 2 = 2.065 , df= 2, |

| Christian | 4 6.6% | 4 3.1% | 8 4.2% | p= 0.356 |

| Total | 61 100.0% | 131 100.0% | 192 100.0% | |

| Victim of Domestic | ||||

| Education | Violence | Total | Significance | |

| Yes | No | |||

| SSC or | 26 | 51 | 77 | |

| equivalent | 42.6% | 38.9% | 40.1% | |

| HSC or | 30 | 58 | 88 | |

| equivalent | 49.2% | 44.3% | 45.8% | |

| Graduate | 3 4.9% | 12 9.2% | 15 7.8% | X 2 = 2.582, df= 3, p= 0.461 |

| Post | 2 | 10 | 12 | |

| graduate | 3.3% | 7.6% | 6.3% | |

| Total | 61 100.0% 100.0% 131 | 192 100.0% | ||

| Husband Education | Victim of Domestic Violence Yes No | Total Significance | ||

| SSC or | 08 | 04 | 12 | |

| equivalent | 13.1% | 3.1% | 6.3% | |

| HSC or | 25 | 34 | 59 | |

| equivalent | 41.0% | 26.0% | 30.7% | |

| Graduate | 19 31.1% | 66 50.4% | 85 44.3% | X 2 = 16.709, |

| Post graduate | 8 13.1% | 27 20.6% | 35 18.2% | df= 4, p= 0.002 |

| Others | 01 1.6% | 00 0.0% | 01 0.5% | |

| Total | 61 100.0% | 131 100.0% 100.0% 192 | ||

| Monthly Income | Victim of Domestic Violence | Total Significance | ||

| Yes | No | |||

| 10001-20000 | 21 34.4% | 37 28.2% | 58 30.2% | |

| 20001-30000 | 26 42.6% | 23 17.6% | 49 25.5% | |

| 30001-40000 | 6 9.8% | 23 17.6% | 29 15.1% | X 2 = 20.383, |

| 40001-50000 | 5 8.2% | 33 25.2% | 38 19.8% | df= 4, p= 0.000 |

| 50001-70000 | 3 4.9% | 15 11.5% | 18 9.4% | |

| Total | 61 100.0% 100.0% 100.0% 131 192 | |||

| Husband Income | Victim of Domestic Violence Yes No | Total | Significance | |

| 1001-10000 | 0 0.0% | 1 0.8% | 1 0.5% | |

| 10001-20000 | 23 37.7% | 25 19.1% | 48 25.0% | X 2 = 11.258, df= 3, Significant= |

| 20001-30000 | 27 44.3% | 56 42.7% | 83 43.2% | 0.010 |

| 30001-50000 | 11 | 49 | 60 19.8% | |

| Total | 61 | 131 | 192 | |

| 100.0% 100.0% 100.0% | ||||

| Victim of Domestic | ||||

| Family Income | Violence Yes No | Total Significance | ||

| 20001-30000 | 6 9.8% | 1 0.8% | 7 3.6% | |

| 30001-40000 | 14 23.0% | 28 21.4% | 42 21.9% | |

| 40001-50000 | 17 27.9% | 23 17.6% | 40 20.8% | X 2 =14.977, df=3, p=.002 |

| 50001-70000 | 24 39.3% | 79 60.3% | 103 53.6% | |

| Total | 61 | 131 | 192 | |

| 100.0% 100.0% 100.0% | ||||

| Earning Member | Victim of Domestic Violence | Total | Significance | |

| Yes | No | |||

| Self | 7 11.5% | 29 22.1% | 36 18.8% | |

| Husband Both | 4 6.6% 50 82.0% | 14 10.7% 88 67.2% | 18 9.4% 138 71.9% | X 2 = 4.547, df= 2, p= 0.103 |

| Total | 61 100.0% 100.0% 100.0% 131 192 | |||

| Family Members | Frequency | Percent |

| 3-5 | 5 | 16.1 |

| 6-8 | 22 | 71.0 |

| 9-11 | 4 | 12.9 |

| Total | 31 | 100.0 |

| Statistics | Mean ± SD (6.97±1.278) |

| Physical Violence | Frequency | Valid Percent |

| Beating | 9 | 69.2 |

| Slapping | 4 | 30.8 |

| Total | 13 | 100.0 |

| Reasons for abusing physically Frequency | Valid Percent | |

| Related to appearance | 4 | 30.8 |

| Related to household matter | 1 | 7.7 |

| Related to your children | 3 | 23.1 |

| Related to your paternal | 4 | 30.8 |

| l ti Related to dowry | 1 | 7.7 |

| Total | 13 | 100.0 |

| Types of mental violence | Frequency Percent | |

| Using abusive language | 19 | 31.7 |

| Stop talking | 5 | 8.3 |

| Restricting from doing things what she like | 10 | 16.7 |

| Restricting decision making in the family | 8 | 13.3 |

| Creating pressure to do things what you does not like | 15 | 25.0 |

| 3 | 5.0 | |

| Total | 60 | 100.0 |

| Table 18 reveals that most (47.4%) common | ||

| reason of the economic violence was not willing to | ||

| spend for the family. Approximately 26.3% had multiple | ||

| families of the husband that was another common | ||

| reason and only 10.5% were related to dowry. | ||

| Reason of abuse | Frequency | Percent |

| Unemployment of the husband | 3 | 15.8 |

| Not willing to spent for the family | 9 | 47.4 |

| Dowry | 2 | 10.5 |

| Multiple families of the husband | 5 | 26.3 |

| Total | 19 | 100.0 |

| Types of abused | Frequency Valid Percent | |

| Forceful intercourse | 2 | 22.2 |

| Promiscuity of the husband | 6 | 66.7 |

| Husband having suspicion on the working women | 1 | 11.1 |

| Total | 9 | 100.0 |

| By whom abused | Frequency | Percent |

| Husband | 44 | 74.6 |

| Mother-in-law | 13 | 22.0 |

| Father-in-law | 2 | 3.4 |

| Total | 59 | 100.0 |

| Types of preventive | Frequency Percent | |

| Try to get help from in-laws | 17 | 41.5 |

| Try to get help from paternal side of the respondent | 6 | 14.6 |

| Try to get help from different NGOs working for women | 1 | 2.4 |

| Tolerated all by herself without any protest | 16 | 39.0 |

| Others | 1 | 2.4 |

| Types of treatment | Frequency | Percent |

| Psychiatric treatment/take medicine | 7 | 3.6 |

| Psychological counseling | 5 | 2.6 |

| Total | 12 | 6.3 |