1. AssociationbetweenPeriodontitisandSevereAsthmaTheRoleofIgGAntiPorphyromonasgingivalislevels

2. Strictly as per the compliance and regulations of:

Abstract-Asthma and periodontitis are both very prevalent worldwide. Although the association between these diseases has been investigated, the biological mechanism underlying this association, especially the role of biological mediators, remains unclear. Thus, the aim of this study was to evaluate serum levels of anti-Porphyromonas gingivalis IgG in subjects with and without severe asthma. A case-control study involving 169 individuals consisted of subjects with severe asthma in addition to others without asthma (control group). An indirect enzyme linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) was performed to measure serum levels of IgG specific to Porphyromonas gingivalis. Bacterial DNA was extracted from subgingival biofilm samples and real-time polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) analysis was performed to quantify Porphyromonas gingivalis levels.

3. I. Introduction

evere asthma and periodontitis are chronic diseases highly prevalent worldwide, affect individuals ? 18 years (1,2) . Asthma, an inflammatory disease affecting the airways, is characterized by increased bronchial responsiveness and reversible airflow limitations, i.e. frequent episodes of shortness of breath and gasping, thoracic oppression and coughing (2) . Of the individuals affected by asthma, 10% suffer from its severe form, leading to negative economic and social impacts. The recurrent suffocation experienced results in human suffering and decreases in quality of life (3) .

Among the chronic diseases that are predominant nowadays, the relationship between asthma and oral health has been a relevant topic of discussion (4) . The presence of chronic infections seems to influence the pathogenesis of asthma, and a wide range of phenotypes and endophenotypes have been observed (5) .

Many studies have demonstrated a positive association between asthma and periodontitis (6)(7)(8)(9)(10) . However, other studies found a negative association and attempted to explain this using the hygiene hypothesis. Accordingly, a high prevalence of oral infectious diseases may contribute to decreases in the incidence of asthma and other allergic diseases. Thus, exposure to oral bacteria, including periodontal disease pathogens, could play a protective role in the development of asthma and allergies by polarizing the immune response (13,14) .

Recently, a new model describing the pathogenesis of periodontitis was proposed, in which the onset of periodontal disease is promoted by a synergistic and dysbiotic microbial community, instead of a specific group of bacteria referred to as periodontopathogens. Some bacteria present at low levels in the microbiota can affect the entire community. Due to their important role in the development of dysbiosis, these are denominated "keystone pathogens" (15) . Of these, one of the most studied is Porphyromonas gingivalis, a Gram-, strictly anaerobic and asaccharolytic bacterium belonging to the Bacteroidaceae family, has been consistently associated with human periodontitis (15,16) .

Confirming the role of Porphyromonas gingivalisin the etiology and pathogenesis of periodontitis, high levels of specific IgG against this bacteria were found in the sera of affected individuals (17,18) . Moreover, individuals with chronic periodontitis presented higher levels of IgG against Porphyromonas gingivalis antigens, such as HmuY and the gingipains proteinases, than healthy individuals, or those with gingivitis (17)(18)(19)(20)(21) .

Due to the public health relevance of these two highly prevalent chronic diseases, asthma and periodontitis, and the gaps in knowledge regarding associations between them, specifically concerning the role of biological molecules, the present study aimed to investigate associations between these two chronic diseases, as well as to evaluate levels of IgG specific to the crude extract of Porphyromonas gingivalis, and HmuY, a lipoprotein of this bacteria.

4. II. Material and Methods

5. a) Study Design

The present non-matched case-control study was performed to evaluate the serum humoral immune response against Porphyromonas gingivalis in severe asthma. The case group consisted of individuals with severe asthma, while individuals in the control group did not have asthma. The case: control ratio was 1:2.

6. b) Participants and study area

Asthmatic participants were enrolled at the ProAR clinic (Program for Asthma Control in Bahia), located in Salvador, Bahia, Brazil. This study was approved by the IRB of the Feira de Santana State University (protocol no. 43131615.3.0000.0053).

Study volunteers were informed of the research protocol and required to sign a term of free and informed consent. Interviews were conducted to obtain background information regarding socioeconomic status, medical history, lifestyle and health habits, as well as oral hygiene habits and frequency of dental visits.

7. c) Selection criteria

Individuals were seen at the ProAR clinic, part of the multidisciplinary municipal health center (Centro de Saúde Carlos Gomes), located in Salvador, Bahia, Brazil, were selected based on a diagnosis of severe asthma. For each participant in the case group, two other nonasthmatic individuals were selected from the patient pool of the municipal health center for inclusion in the case group, provided they resided in the same neighborhood as the case participant. To not introduce bias, all control individuals were recruited from the dental services division of the municipal health center on days in which a periodontal specialist was not present.

8. d) Sample size calculation

Sample size was calculated based on a previously reported proportion of individuals with periodontitis (61.9%) within a group of severe asthmatic patients versus 27.1% in a group without asthma (6) . Thus, considering an odds ratio of 4.37,a significance level of 95%, a power of 80% for two-tailed testing, and a case: control ratio of 1:2, the minimum sample size was 54 individuals for the CASE group and 108 individuals for the CONTROL group.

9. e) Periodontal Diagnosis

Individuals were considered to have periodontitis when at least four teeth presented one or more sites meeting all of the following conditions: probing depth ? 4mm, clinical attachment level ? 3mm, and bleeding on probing after stimulation (22)

10. f) Diagnosis of Severe Asthma

The diagnosis of asthma was made by GINA, 2012 7 . Before the inclusion, a revision in the medical records of each participant was realized, and only those who received a diagnosis by two specialists and confirmed by spirometry were included.

11. g) Peripheral blood collection

Peripheral blood (5 mL) was collected by venipuncture in the antecubital fossa from all participants and stored in Vacutainer tubes (BD, SP, Brazil) with clot activator. The tubes were centrifuged for 10 min to obtain sera, which was stored at -20º until analysis.

h) Antigen obtainment P. gingivalis ATCC33277 was grown in Brucella broth supplemented with menadione and L-cysteine, and then somatic immunogenic proteins were obtained by centrifugation (18). The recombinant protein HmuY (rHmuY) of Porphyromonas gingivalis was cloned from Escherichia coli using a plasmid as a cloning vector, then purified and characterized.

12. i) ELISA to measure IgG against antigens of Porphyromonas gingivalis

An enzyme linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) was used to evaluate the humoral immune response against a crude extract of Porphyromonas gingivalis and the rHmuY protein using an indirect measure of IgG levels in the sera of the participants.

A 96-well plate was coated with 5µg/mL of antigen (P. gingivalis crude extract or rHmuY) and incubated overnight at 4ºC. After washing with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), blocking was performed using 5% skim milk (Molico, Araçatuba, Brazil). After reincubation for 2h at 37ºC, the plates were washed twice, and diluted sera (1:1000) was placed in each well, followed by an incubation period of 1h at 37ºC. All wells were then washed five times with PBS and reincubated with anti-human IgG conjugated with peroxidase (Sigma Aldrich, USA) diluted at 1:25000 for 1h at 37ºC. After five additional washes, a chromogenic substrate (H 2 O 2 -TMB) was added, and the reaction was stopped using 2N H 2 SO 4 . IgG levels were measured by optical density (OD) using a microplate reader (PR2100 Bio-Rad, USA) at wavelengths ranging from 450-620 nm.

13. j) Biofilm Collection

Following periodontal examinations, subgingival biofilm was collected using a periodontal curette from the site with the greatest probing depth in each sextant (Hu-Friedy, USA). Samples were pooled in a microtube containing sterile PBS (one tube for each patient), and, after centrifugation, pellets were stored at -20ºC until DNA extraction.

14. k) Bacterial DNA Extraction and Genotyping

Bacterial DNA was extracted from subgingival biofilm samples using a PureLink? Genomic DNA Mini Kit (Invitrogen) by the manufacturer's protocol.

The relative quantification of P. gingivalis was performed using the TaqMan ® probe quantitative realtime polymerase chain reaction (qPCR) method. The probe sequence used in the reaction was: 5'-6-FAM-CRA ACA GGA TTA GAT ACC CTG GTA GTC CRC-BHQ1 -3'. The primer sequence was: forward -5'-GAC TGA CAC TGA AGC ACG AAG -3' and reverse -5'-GCT TGA CGG TAT ATC GCA AAC TC -3'. The PCR mix (final volume of 12.5 µl) consisted of: 10xbuffer (1.25µl) containing 50mMMgCl 2 (0.38µl),4x2.5mM(1µl), 10 µM forward primer (0.38 µl), 10 µM reverse primer (0.38 µl), 5U/µl Taq (0.05 µl), RNase-free water (6.33 µl), 10 µM probe (0.25 µl) and DNA (2.5 µl). Reactions were performed using an initial denaturation cycle at 94ºC for 1 min, 45 cycles at 94ºC for 20 sec, and 58ºC for 35 sec.

15. l) Statistical Analysis

Descriptive statistical analysis was carried out using the Student T-test for continuous variates and the chi-square test, or Fisher´s exact test, for dichotomous variates. Comparisons of IgG levels were made using the Mann-Whitney test. The association between periodontitis and severe asthma was evaluated by logistic regression, using the backward strategy to select confounders. All statistical analyses were performed using the SPSS v21 statistical package, and the results were considered statistically significant when p ? 0.05.

16. III. Results

A total of 169 individuals were included in the study. The group with severe asthma (case) consisted of 53 Participants (31.4%), while 116 participants (68.6%) were included in the group without asthma (control). The mean age in the case group was 49.5±12.1 years, versus 43.95±11.4 years in the control group. In the case group, 45 (84.9%) participants were female, and eight (15.1%) were male, while the control group consisted of 100(86.2%) females and 16 (13.8%) males. No statistically significant differences were detected between the groups in terms of age (P=0.17) or sex (P=1.0), nor concerning the socioeconomic and demographic characteristics evaluated (Table 1), demonstrating homogeneity regarding these covariates.

Table 2 delineates the distribution of aspects related to lifestyle habits and oral health in the groups with and without severe asthma. No statistically significant differences were observed between cases and controls concerning these aspects, except for mouth-breathing habit (P <0.01).

Table 3 lists characteristics related to the general health status of the participants. While homogeneity was observed between the case and control groups, statistically significant differences were seen about diagnoses of periodontitis (P<0.01) and hypertension (P<0.01).

A positive association between periodontitis and severe asthma was observed (OR = 6.73 [2.57-17.64]), even after adjusting for mouth breathing, hypertension, body mass index (BMI) and practicing physical activity (OR=7.96 [2.65-23.9]). The frequency of periodontitis in the case group was 30.8% versus 6%, in the control group, i.e, the chance of having severe asthma was almost eight times higher among individuals with periodontitis.

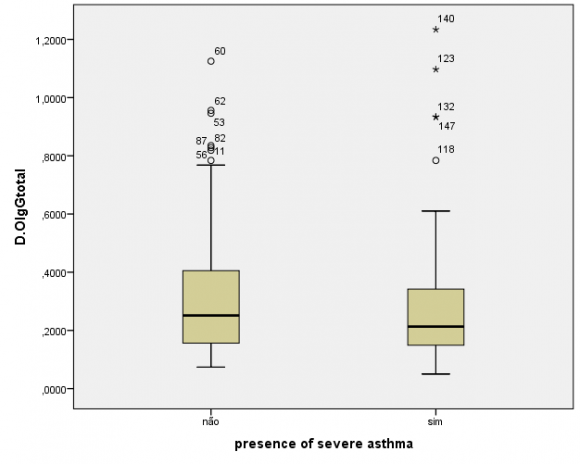

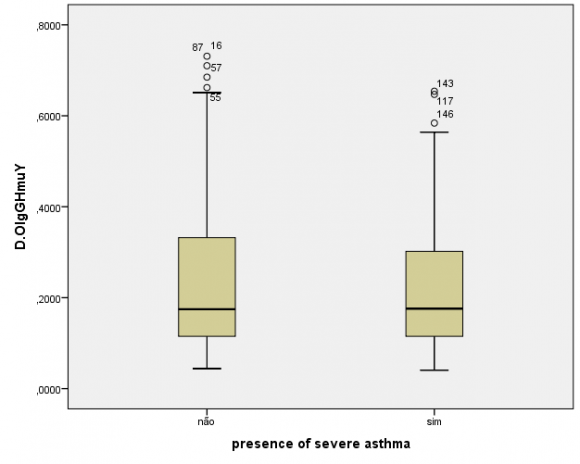

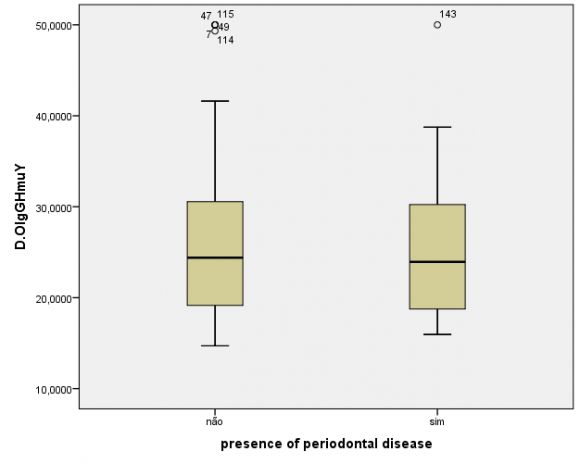

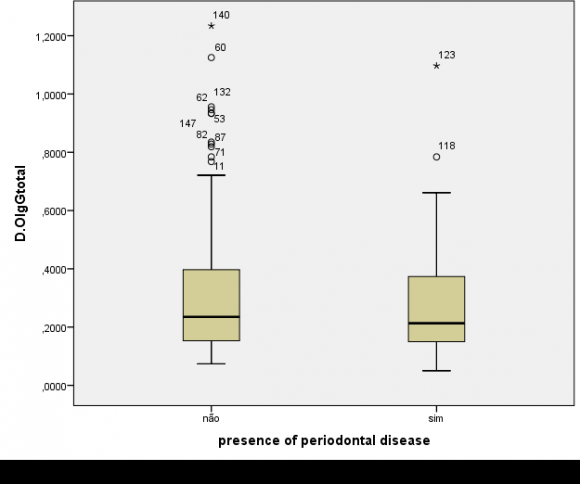

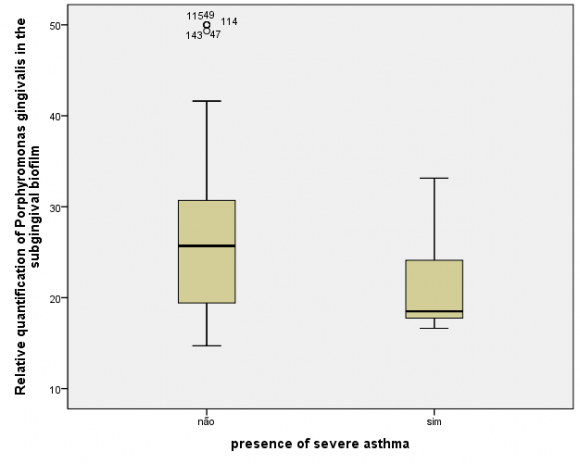

The humoral evaluation found ,no statistically significant differences in levels of IgG specific to the crude extract (P=0.48) or rHmuY (P=0.90) between the case and control groups, as illustrated in Figures 1 and 2, respectively. Moreover, IgG levels specific to the crude extract (P=0.79) and to rHmuY (P=0.63) were similar among individuals with or without periodontitis, as shown in Figures 3 and 4, respectively. Also, we found no statistically significant differences in the relative amount of Porphyromonas gingivalis (P=0,05) among participants with severe asthma and those without asthma (Figure 5). Unexpectedly, significantly lower relative amounts of Porphyromonas gingivalis (P?0,001) were observed in the biofilm of individuals with periodontitis in comparison to those without periodontitis (Figure 6).

17. IV. Discussion

The main finding of the present study was the establishment of a strong association between periodontitis and asthma, even after adjusting for confounders, indicating that individuals with periodontitis are more likely to suffer from asthma. Another relevant result was similar production levels of IgG specific to P. gingivalis among the participants, regardless of whether they had severe asthma, periodontitis, or neither of these conditions. While the literature indicates that individuals with periodontitis are expected to harbor significantly higher levels of IgG specific to Porphyromonas gingivalis (17) , the present results were divergent. This would seem to suggest that the presence of severe asthma may influence the humoral response to Porphyromonas gingivalis, the relative quantities of Porphyromonas gingivalis were found to be significantly lower in the subgingival biofilm of individuals with chronicperiodontitis.

To date, the literature is controversial regarding the relationship between periodontitis and asthma. Several studies have shown positive associations (7,(23)(24)(25)(26) in individuals with periodontitis, who are five times as likely to present bronchial inflammation (6) , or have a three times greater chance of developing severe asthma (27) . By contrast, other studies have reported either a negative association (13) or demonstrated the absence of any relationship between these diseases (11,12) .

Possibly due to this lack of concordance, there are no reports in the literature that attempt to confirm this association on a molecular level. To an effort to investigate this association, we sought to evaluate serum levels of IgG against antigens of Porphyromonas gingivalis, a keystone microorganism in periodontal dysbiosis (15,28) , which is prevalent in deep periodontal pockets (16) .

In contrast to the findings reported herein, previous studies have shown that individuals with periodontitis present high levels of IgG specific to Porphyromonas gingivalis extract, as well as toitslipoprote in HmuY. The literature indicates a remarkable discrepancy regarding IgG levels in individuals with a clinical diagnosis of periodontitis, those with gingivitis, and others with sound periodontal health (18,19,35) . Nevertheless, is important to emphasize that these studies did not include individuals diagnosed with any other diseases, nor those taking medications, such as corticosteroids, which like this eliminated agents capable of modulating host response.

Given this fact, it is possible to speculate that, in individuals with chronic periodontitis, the presence of severe asthma may modulate the production of IgG specific to Porphyromonas gingivalis, which reinforces the bidirectional association between these two diseases. Regardless, further investigation is necessary to clarify whether this modulation occurs by way of immune system regulation.

Furthermore, it is possible that the similarities seen in levels of IgG specific to the Porphyromonas gingivalis extract and HmuY, in individuals with and without severe asthma, may be related to possible interactions between periodontal tissues and the drugs used to control the clinical symptoms of asthma (23,25) . The immunosuppressant effect of corticosteroids can influence the host immune response seen in periodontal tissues, including the production of IgG (36) . Moreover, it is possible that the presence of asthma provokes changes in the periodontal microenvironment, which may alter the colonization, in the subgingival biofilm, of members of the microbial community. Herein, surprisingly, the relative quantities of Porphyromonas gingivalis were found to be higher in individuals without periodontitis.

As previously mentioned, this microorganism is capable of modulating host defense by altering the growth and development of the entire microbial community, i.e. eliciting destructive changes in the relationships among its members, which is normally homeostatic. Porphyromonas gingivalis is considered to be a keystone pathogen that, when present even in low amounts in the biofilm, can provoke, an imbalance between host response and the biofilm, which may favor the onset and progression of periodontitis (15) .

It is important to consider that some studies argue that the presence of periodontitis may offer protection against asthma. This is justified by the hygiene hypothesis, which holds that fewer opportunities for infection are responsible, at least in part, for increases in the prevalence of allergic diseases (11)(12)(13) .

In this context, a study reported that Porphyromonas gingivalis can reduces inflammation in the airways, although this effect did not affect the hyperreactivity of these airways (14) . Also, high concentrations of serum IgG against Porphyromonas gingivalis were also found to be significantly associated with a lower prevalence of asthma and sibilance (13) . The present study represents an initial attempt to investigate the molecular aspects of the association between periodontitis and asthma. A link between levels of Porphyromonas gingivalis in the subgingival biofilm and, the humoral immune response against this bacterium was found. Moreover, the relative quantification of the bacterium was performed via a widely used sensitive technique. Also, the immunoassays employed to evaluate IgG levels were previously standardized, and the capacity to distinguish among a variety of periodontal conditions was also demonstrated (35) .

About limitations, due to the present casecontrol design, there was no way to establish which disease preceded the other, as both are chronic diseases. The possibility of residual confoundment may also exist, since some covariates, such as genetic factors, may not have been considered.

Thus, in light of its limitations, the present study seems to suggest that the occurrence of severe asthma is capable of modulating the colonization of Porphyromonas gingivalis in the subgingival biofilm, in addition to the production of IgG specific to antigens of this bacterium (extract and HmuY) in the sera of individuals with periodontitis.

18. Tables and Figures

| Association between Periodontitis and Severe Asthma: The Role of IgG Anti-Porphyromonas |

| gingivalis Levels |

| gingivalis Levels |

| Without asthma | Severe asthma | ||

| (N=116) | (N=52) | ||

| Hypertension | N (%) | N (%) | p** |

| Not | 95 (81,9%) | 29 (54,7%) | |

| Yes | 21(18,1%) | 24(45,3%) | |

| Diabetes | N (%) | N (%) | p** |

| Not | 109 (94,0%) | 46(86,8%) | 0,14 |

| Yes | 7(6,0%) | 7(13,2%) | |

| Osteoporosis | N (%) | N (%) | p** |

| Not | 115(99,1%) | 51(96,2%) | 0,23 |

| Yes | 1 (0,9%) | 2 (3,8%) | |

| Kidney disease | N (%) | N (%) | p** |

| Not | 115(99,1%) | 53 (100%) | 1,00 |

| Yes | 1 (0,9%) | 0(0%) | |

| Hypercholesterolemia | N (%) | N (%) | p** |

| Not | 110 (94,8%) | 46(86,8%) | 0,01 |

| Yes | 1(0,9%) | 7(13,2%) | |

| Cardiovascular disease | N (%) | N (%) | p** |

| Not | 115(99,1%) | 84(93,3%) | 0,04 |

| Yes | 1 (0,9%) | 6 (6,7%) | |

| Body mass index (weight / height²) | N (%) | N (%) | p** |

| < 25 | 42(36,2%) | 11 (20,8%) | 0,05 |

| ?25 | 74 (63,8%) | 42(79,2%) | |

| Diagnosis of periodontitis * | N (%) | N (%) | p*** |

| Without periodontitis | 109 (94%) | 36(69,2%) | <0,01 |

| With periodontitis | 7 (6%) | 16 (30,8%) |