1. I. Introduction Deep Vein Thrombosis:

Dvt irst-time episodes of deep vein thrombosis (DVT) are in two-thirds of cases caused by risk factors, including varicosis, cancer, immobility, or surgery, oral contraceptives and thrombophilia (table 1) 1,2. Alterations in blood coagulability with changes in blood flow and endothelial damage, are the precursors of intravenous thrombosis. A number of other hereditary and acquired conditions that predispose to thrombosis (thrombophilia) have been recognized. These include protein C and S deficiency, antithrombin III deficiency and activated protein C resistance (which is usually associated with a factor V genetic abnormality 3 . Screening for these thrombophilia and for anticardiolipin antibody, should only be performed in patients having familial, sporadic or recurrent thrombosis.

Duplex Ultrasound, Clinical Score, and D-Dimer to Rule in and Out Deep Venous Thrombosis (DVT) and Postthrombotic Syndrome (Pts): Bridging the Gap between DVT and Ptsin the Primary Care and Hospital Setting A first DVT event in adults and elderly has a gradually increasing 20 to 30% DVT recurrence rate after 5 years followup. Research studies show that complete recanalization on DUS within 1 to 3 months and no reflux is associated with with low recurrence of DVT (1.2% patient/years) and withno PTS obviating the need of MECS and anticoagulation after 3 to 6 months post-DVT respectively. Delayed recanalization at 3 months post-DVT and the presence of reflux due to valve destruction on DUS at 3 months post-DVT is associated with a high risk of DVT recurrence as the cause of symptomatic PTS indicating the need to wear MECS and extend anticoagulation.

2. DVT

The onset of a thrombosis is often 'silent' and may remain so. It commonly occurs at or about day 7 to 10 after a surgical operation, parturition or the onset of an acute infection. Between one-third and two-thirds of patients complain of some swelling and pain in the leg, usually in the calf [1][2][3] . An iliac thrombosis should be suspected if the whole leg is swollen and dusky. Direct pressure on the calf muscles or over the course of the deep veins usually elicits direct tenderness. There may be a cyanotic hue to the leg and superficial venous dilatation. The temperature of the leg may be raised, and oedema of one ankle is an important physical sign. However, chest pain or cardiac arrest from pulmonary embolism may be the first indications of a DVT. Pulmonary hypertension may follow repeated small emboli, and is associated with the development of progressive dyspnoea.

Pain and tenderness in the calf and popliteal fossa may occur resulting from alternative diagnoses (AD) like conditions such as a ruptured Baker's cyst, a torn plantaris tendon, a hematoma, or muscle tears or pulls. Cutaneous infection (e.g. cellulitis), lymphoedema, venous reflux, peripheral arterial disease, and rheumatological causes should also be differentiated from DVT.

As compared with phlebography (the reference gold standard to exclude and diagnose proximal DVT in prospective management studies), the sensitivity of compression ultrasonongraphy (CUS) is 97% for proximal and 73% for distal vein thrombosis 4,5 . CUS has many advantages over phlebography. It is noninvasive, simple, easy to repeat, relatively inexpensive, and free of complications. However, there are two main disadvantages of CUS. First, calf vein thrombosis will be overlooked by CUS because it is safe to limit CUS estimation to the subpopliteal, popliteal, and femoral veins for the diagnosis of symptomatic proximal DVT. Second, isolated thrombi in the iliac and superficial femoral veins within the adductor canal are rare but difficult to detect and therefore easily overlooked in symptomatic patients with suspected DVT (10).

Estimates of clinical score as low, moderate, and high for the probability of proximal DVT, based on medical history and physical examination is the first step when DVT is suspected (Table 2) 4,5 . A score of 0 (asymptomatic) means a low probability, a score of 1 or 2 a moderate probability, and a score of 3 or more a high probability for DVT.

3. Clinical feature Score

Active cancer treatment ongoing or within previous 6 months or palliative 1

Paralysis, paresis, or recent plaster immobilization of the lower leg(s) 1

Recent immobilization for more than 3 days or major surgery within last 4 weeks 1

Localized tenderness/pain along the distribution of the deep venous system 1

4. Entire leg swollen 1

Calf swelling by more than 2 cm when compared with the asymptomatic leg 1

(measured 10 cm below tibial tuberosity)

Pitting oedema greater in the symptomatic leg 1

5. Collateral superficial veins (nonvaricose) 1

Total Rotterdam DVT score 8 mat ity)

Tabel 2 : Clinical score list for predicting pretest probability for proximal DVT The Rotterdam modification of the Wells' score 4,5 .

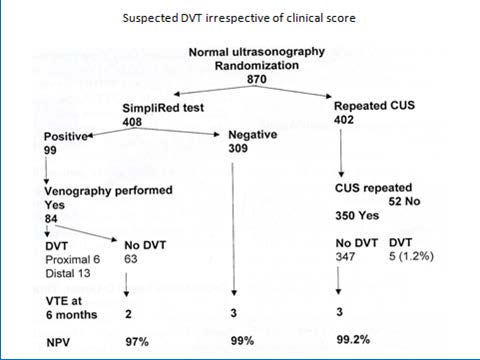

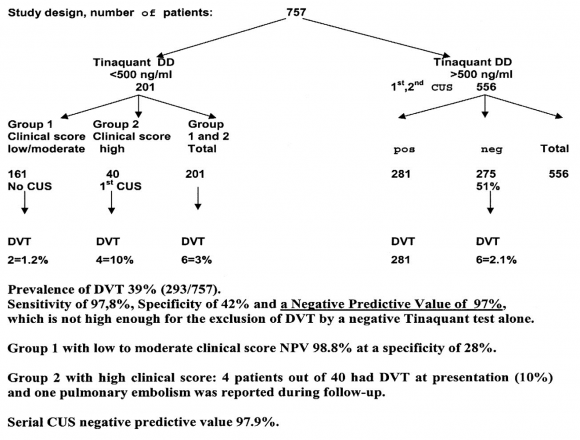

D-dimer is a degradation product of a crosslinked fibrin clot. It has gained a prominent role for ruling out DVT. The prevalence of DVT after a negative first CUS is uniformly low, 2 to 3%, during a 3 months followup with a NPV of 97 to 98% in large prospective management studies (figure 1)4. The combination of a negative first CUS and a negative SimpliRed safely excludes DVT to zero or less than 1% (NPV > 99.3 to 100%) irrespective of clinical score (figure 1) (11). This simple, safe and most effective strategy obviates the need of repeated CUS on the basis of which anticoagulant therapy can safely be withheld and reduces the number of repeated CUS testing from about 75% to 30% (figure 1) 6 .

Figure 1 : Safe exclusion and diagnosis of deep vein thrombosis by the sequential use of CUS and SimpliRed test in the primary care setting or outpatient ward 6 The negativepredictivevalue of a normalqualitative D-dimerSimpliRedtest is not high enoughfor the exclusion of DVT 4,5 . After a negativefirst CUS and a negativeSimpliRed (Simplify) test DVT isexcludedwith anegativepredictivevalue of 99.0% with the needtorepeat a second CUS when the D-dimer is positive (Figure 1) 6 .

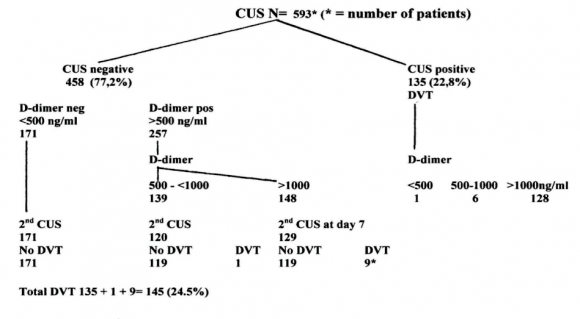

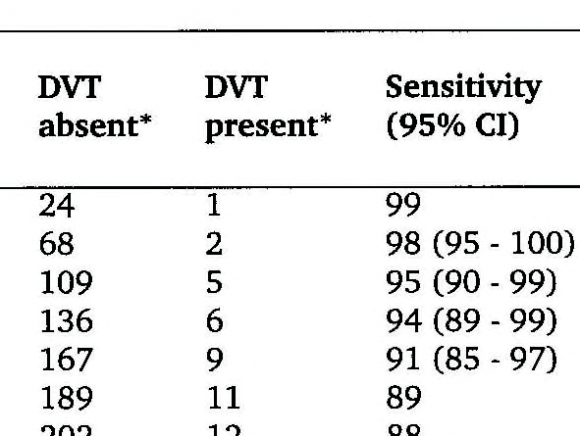

The feasibility of a strategytoexclude DVT by a negativerapid ELISA VIDAS D-dimer test (<500 ng/ml) alone without the need of CUS, on the basis of whichanticoagulant treatment is withhold, has been tested in the large prospective management Geneva study (table3) 6 In thisGeneva study of 474 outpatientswithsuspected DVT, the sensitivity and negativepredictivevalue(NPV) of a rapid ELISA D-dimer test forthrombosisexclusionwere 98.2 and 98.4% respectively (table 3). A negative CUS followedby a negative ELISA VIDAS D-Dimertest result (<500 ng/mL) exclude DVT and pulmonaryembolismwith a sensitivity, and NPV of 100% irrespective of clinical score (table 3 left arm, Geneva Study) 7 .

Table 3 : Results of CUS and ELISA D-dimertesting in 593 patientswithsuspected DVT in the prospective Geneva management study 7 .

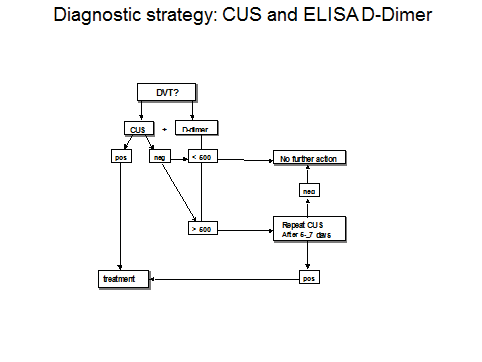

We tested the sequential use of the sensitive quantitative ELISA VIDAS D-dimer test, clinical score, and compression ultrasound (CUS) as a safe and costeffective diagnostic work-up of DVT in a large prospective management study according to the diagnostic algorithm in figure 2A. According to figure 2A DVT is excluded after a negative CUS and normal VIDAS D-Dimer (<500 n g/m L) with a sensitivity and NPV of 100%. If the first CUS is negative and the VIDAS D-dimer increased (>500 n g/m L) a second CUS was performed within one week.

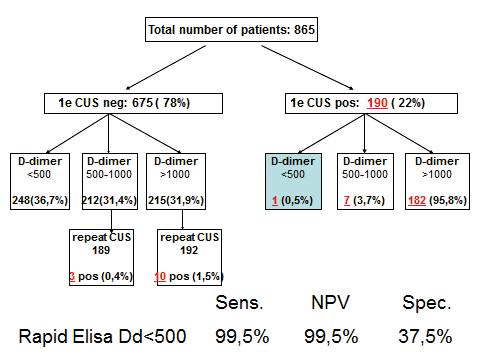

Out of 865 outpatients with suspected DVT, a 1st CUS was negative in 675 , and positive in 190 (22%). In 249 outpatients with a normal ELISA VIDAS (<500 n g/m L) the CUS was true negative in 248 and false negative in 1 (sensitivity 99.5%, figure 2B). The negative predictive value of a first CUS was 98.6% (662 out of 675) on the basis of which a second CUS within one week should beper for med. A 2nd CUS was indicated in 427 and performed in 382 because of increased ELISA VIDAS D-dimer (>500 n g/m L) and proved to be positive in 13 (1.9% of 381).

The overall prevalence of DVT in o rprospective management study was 190 plus 13 = 203 (23.4%, figure 2 B). The prevalence of DVT on CUS at increasing ELISA VIDAS cut off levels of 0 to 500 (N=249), 500 to 1000 (N=196) and above 1000 n g/m (N=374) was 0.5%, 5.1% and 19.5%. A normal ELISA VIDAS D-dimer test (<500 ng/mL) aloneex cluded DVT at a sensitivity and NPV of 99.5% and a specificity of 37.5% (figure 2 B).

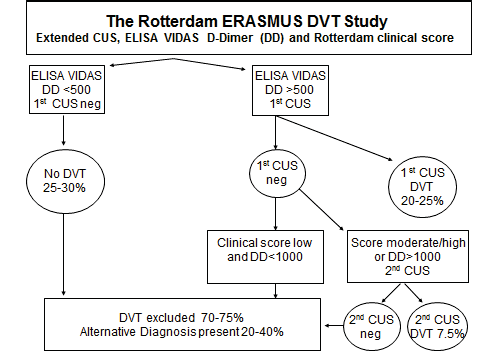

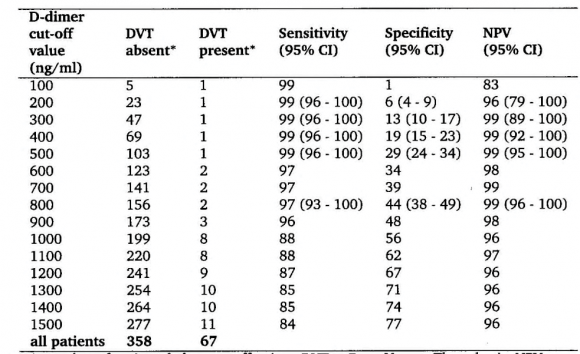

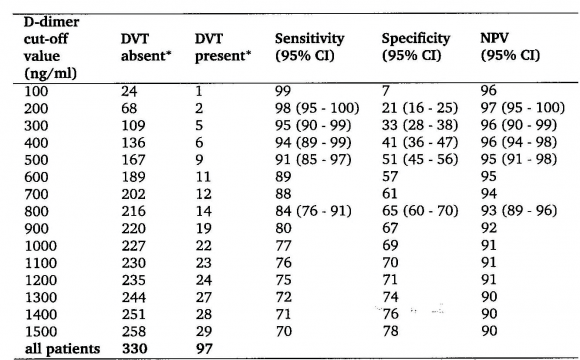

The sensitivit y for DVT exclusion of an ELISA VIDAS test result between 500 and 1000 n g/m L after a first negative CUS was 99.6 as test edbyrepeated CUS. The combination of a first negative CUS and an ELISA VIDAS test between 500 and 1000 n g/m L will exlude DVT with a NPV of 99.7% (figure 2B). From this prospective management study we concluded that the combined use of a sensitive quantitative ELISA D-dimer test, clinical score, and compression ultrasound (CUS) is a safe and costeffective diagnostic work-up to exclude and diagnose according to the algorithm in figure 3. First, it is safe to exclude DVT and pulmonary embolism by a negative CUS and normal ELISA D-Dimer test (<500 n g/ml, left arm) with a sensitivity and NPV of 100%. Second, it is safe to exclude DVT by a first negative CUS and an ELISA VIDAS D-Dimer test result of <1000 n g/m L in asymptomatic cases with a low clinical score of zero (middle arm) with a sensitivity and NPV of 99,6%. Third, attentive clinicians should be aware that the combination of a negative first CUS and an ELISA D-Dimer test above 500 n g/m L in patients with persistent complaints, signs and symptoms suspected for DVT are candidates to perform a second CUS (right arm, figure 3). This new strategy in figure 3 is predicted to l reduce repeaedt CUS testing by two-third, which has been tested in a large prospective management study of more than 2000 patients with suspected DVT between 2006 and 2013 (manuscript in preparation). The sensitivity of a normal (<500 ng/ml) turbidimetric D-dimer assay Tinaquant (Roche Diagnostics, Marburg Germany) for the exclusion of DVT in a large management studywas 97.7% at a specificity of 42% and a NPV 97% (figure 4)8. A normal Tinaquant test result (<500 ng/ml) as a stand alone test appearstobe not sensitiveenough for the exclusion of DVT. The combination of a negative first CUS, a normal Tinaquant test result (<500 n g/ml) and a low clinical score had a negative predictive value of 99.4% without the need of CUS testing and thusreduced the number of CUS testingby 29% (Figure 4) 8 . Those patientsa first negative CUS, a Tinaquant around and above 500 n g/m L and persistent symptom ssuspected for DVT (moderate/high clinical score) are candidate for CUS testing within one week toexclude or diagnose DVT or analternative diagnosis in the primary care setting. 9 . To safely exclude DVT, a high sensitivity and NPV are needed to limit missed DVT cases. At the 500 n g/m L threshold, the ELISA VIDAS assay did meet this criterion (table 4A) in contrast to the Tinaquant. For the Tinaquant D-Dimer assay lower threshold are preferred for excluding DVT in the primary care setting (table 4B). We emphasize that DVT should be diagnosed and excluded based on a non-in vasie strategy with an objective post-test incidence of venous throm boembolism (VTE) of lessthan 0.1% with a negative predictive value of 99.5% to 99.9% during 3 months follow-up 10 .

Modification of the Wells score bye limination of the "minus 2 points" for AD is mandatory and will improve the diagnostic caccuracy of DVT suspicion significantly in the primary care setting and outpatient ward 4,5,10 . The sequentialuse of complete DUS first, followed by ELISA D-Dimer testing and modified clinical Wells' score assessment is safe and effective for the exclusion and diagnosis of DVT and AD.

6. III.

7. Introduction Posthrombotic

Syndrome: PTS

The postthrombotic syndrome (PTS) is a chronic condition that affects the deep venous system, and may also extend to the superficial venous system of the legs in patients with a documented history of deep vein thrombosis (DVT) [11][12][13] . Clinical symptoms of PTS may vary considerably and range from scarcely visible skin changes to changes in pigmentation, pain, discomfort, venous ectasia, oedema, and ulceration. Patients experience pain, heaviness, swelling, cramps, itching or tingling in the affected limb. Symptoms may be present in various combinations and may be persistent or intermittent. Typically, symptoms are aggravated by standing or walking and improve with resting, leg elevation and lying down. Next to varicose veins, a specific sign of early forms of venous incompetence is the so-called corona phlebectatica para plantaris (ankle flare). There are telangiectases surrounding the malleoli of the ankle. Other signs are oedema, hyperpigmentation, and eczema. Signs of more advanced disease are dermato-and liposclerosis, a localized induration of the skin and sometimes of the underlying tissues, with fibrosis and inflammation. Through microthrombi, an area of whitened skin with reddish spots may occur, called atrophie blanche or white atrophy. The most severe sign is the venous leg ulcer, a chronic wound that fails to heal spontaneously or within the time range of normal healing of the skin.

DVT has a recurrence rate of about 20% to 30% after 5 years, but the rate varies depending on the presence of risk factors for thrombosis recurrence and particularly increases after discontinuation of prolonged anticoagulation 11 .The only clear identified risk factor for overt PTS is recurrent or ipsilateral DVT, which increases the risk of PTS several fold 11-13. In a prospective study of 313 consecutive DVT patients, Prandoni et al have shown that Residual Vein Thrombosis (RVT) at any time post-DVT is a risk factor for recurrent VTE. In this study, DUS of the common femoral and popliteal veins was performed at 3, 6, 12 24 and 36 months post DVT. The cumulative incidence of RVT was 61%, 42%, 31%, and 26% at 6, 12, 24 and 36 months (1/2, 1, 2 and 3 years) post DVT respectively. Of 58 VTE recurrent episodes, 41 occurred at time of RVT. The hazard ratio for recurrent VTE was 2.4 with persistent RVT versus those with earlier complete vein renalization2. The post-DVT recanalisation process in patients with acute proximal DVT is completed between 3 months to 2 years, depending on the severity of DVT and the presence or absence of transient or persistent risk factors for thrombosis recurrence and PTS. This observation is in favor to extend anticoagulation at 6 months and 1 year post-DVT when RVT on DUS is present in symptomatic PTS patients during follow-up for about 2 to 3 years or even life-long post-DVT.

The CEAP (Clinical-Etiology-Anatomic-Pathophysiologic) (table 5) for PTS is the best known and widely used by phlebologists but not by clinicians or vascular medicine specialists 3 . In 1992, Prandoni developed an original standardized scale for the assessment of PTS in post-DVT legs. Each subjective sign and objective symptom was scored as 0, 1, 2 or 3 based on subjective judgement 13 . The 5 signs and 7 symptoms of the Prandoni score are taken over by PTS investigators as the Villalta in the literature exactly as first designed by prandoni for use in clinical practice (table 6) 11 . The original Prandoni (subjective Villalta) score of signs and symptoms has never been evaluated against the objective CEAP scoring system as we proposed in table 3. It is mandatory to validate both the Prandoni (Villalta) scoring of signs and symptoms of early PTS in the modern setting of PTS evaluation against objective scoring system in table 3 at 1, 3, 6 and 12 months up to 2 years post-DVT. This statement is of particular interest, since literature data are convincing in showing that PTS is present in about 50% one year post-DVT using the Villalta score as compared, and does not increase in frequency and severity when under continuous medical care. Conclusion: the Prandoni scoring system is an ordered use of CEAP clinical symptoms and signs (C&S) by internist without expert dermatological evaluation and objective testing with CUS. Moreover this scoring system should be used at 1, 3, 6, 9 months and 1 years pos-DVT for the assessment of disappearance or persistence of DVT symptoms and the appearance of mild, moderate and severe PTS symptoms

8. V. Normal Versus Abnormal DUS at 3 Months Post-DVT

The study of Prandoni et al 14 have clearly demonstrated that about half of the DVT patients do not develop PTS in the control group, and that compression therapy using medical elastic compression stockings (MECS) decreases this incidence with 50% (from circa 50 to 25% indicating an absolute reduction rate of 25%) during an observation and treatment period of 2 years following DVT. Family doctors, phlebologists and internists usually treat the acute phase of DVT with anticoagulants for at least 3 to 6 months 1-4 . Physicians with interest and expertise in phlebology are usually confronted much later and frequently too late with overt post-thrombotic complications of DVT [11][12][13][14] .

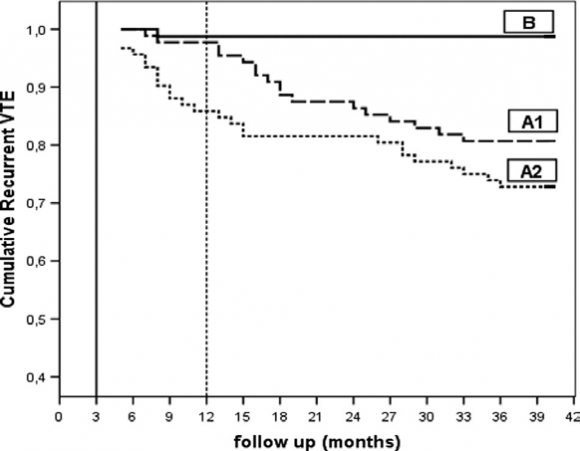

In the study of Siragusa et al 15 follow-up was 1.3% (95% CI, 1-7%, B in figure 5 ). The proportion of provoked vs unprovoked DVT was 64% and 36% indicating that this distinction is artificial in terms of risk assessment. The group of 180 DVT patients with residual venous thrombosis (with no or partial recanalization on DUS) were randomized to stop anticoagulation at 3 months post-DVT (N=92) or to continue anticoagulant for 9 additional months and discontinued 12 months post-DVT. During follow-up from the time of anticoagulation discontinuation recurrent VTE events started to occur in 25 of 92 = 15, 2% person-years who discontinued anticoagulation at 3 months post-DVT (A1 in figure ) and in 17 of 88 patients = 1.1% person-years who discontinued anticoagulation at 12 months post-DVT (A2 in figure 5). Very interestingly, the proportion of provoked vs unprovoked DVT in patient with RVO (incomplete recanalization) at 3 months post-DVT was 23% vs 77% again indicating that this distinction is artificial in terms of risk on DVT recurrence.

Figure 5 : Discontinuation of anticoagulation at 3 months post-DVT in DVT patients with rapid recanalization of leg veins within 90 days (3 months, N=78) is followed by a very low DVT recurrence rate B). In patients with residual vein occlusion on DUS at 3 months post-DVT discontinuation of anticoagulation at 3 months (A2, N=92) or at 12 months DVT (A1, N=88) is followed by increased VTE recurrence rate 15 These two prospective studies demonstrate that half of the patients with a first DVT do not need therapy with MECS in cases with rapid complete recanalization and no PTS at 3 months post-DVT obviating the need of anticoagulant treatment at 6 months post-DVT 14,15. Early mobilisation of the patient, adequate anticoagulant therapy and immediate compression treatment with MECS reduces the chance to develop PTS significantly. In the prospective study of 313 consecutive DVT patients, the cumulative incidence of normal DUS (no RVT) was 39%, 58%, 69% and 74% at 6, 12, 24 and 36 months post DVT respectively. About one quarter of DVT patients had RVO at time point 3 years post-DVT 12 . Of 58 VTE recurrent episodes, 41 occurred at time of RVT. The hazard ratio for recurrent VTE was 2.4 with persistent RVO versus those with earlier complete vein renalization 12 . In view of this, three subsequent yet unanswered questions in the treatment of DVT are 13 VI. Rapid Versus Delayed Recanalization Related to Reflux in Post-DVT Patients Predict PTS Phlebologists generally distinguish two main types of PTS 13 . 1. The reflux type (circa 90%) 2. The obstruction type (circa 10%) In a substantial number of patients only partial re-canalisation (=residual venous occlusion: RVO) occurs as opposed to complete obstruction or nearly complete obstruction. In the prospective study of Prandoni et al the cumulative incidence of complete recanalization was 39%, 58%, 69%, and 74% at 6, 12, 24 and 36 months (1/2, 1, 2 and 3 years) post DVT respectively 12 . Sequential DUS imaging can easily assess this. DVT patients with complete re-canalisation (no RVO) can be divided in two groups 3 : 1. Those with functional (intact) vein valves 2. Those with dysfunctional vein valves Dysfunctional vein valves result in reflux and ultimately in increased venous pressure, which is the main hemodynamic determinant of symptomatic PTS in need for MECS and extended anticoagulation. Asymptomatic post-DVT patients with complete recanalisation but with no reflux or compensated reflux (low risk DVT recurrence) might be candidates for discontinuation of MECS therapy within the period of 2 years 13 .

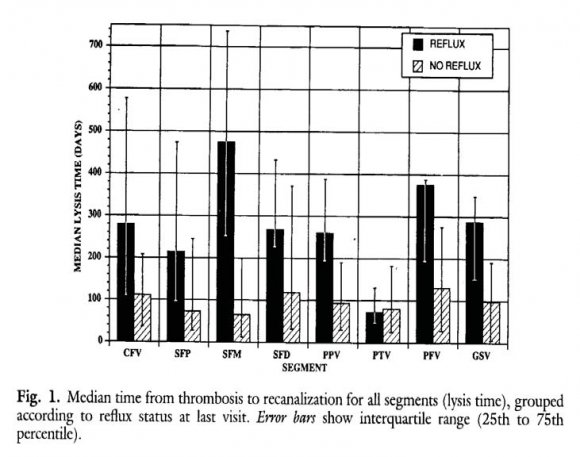

Meissner et al studied the relationship between time to complete recanalization post-DVT (lysis time) and the development of reflux in patients with a first episode of DVT at 3 months interval during the first year (figure 6) 16 . Duplex criteria for complete occlusion were defined as the absence of detectable flow, either spontaneous or with augmentation, in an incompressible venous segment. Partial occlusion was defined as normal or diminished flow, either spontaneous or with augmentation, in an incompletely compressible venous segment. Complete lysis (recanalization) was presumed to have occurred when spontaneous phasic flow returned and the vein was completely compressible 16 . For the posterior tibial veins (PTV), flow detected after distal augmentation in a completely compressible vein is accepted as evidence of complete recanalization (lysis). The median time from DVT to complete recanalization (lysis time) was about 3 months (100 days) for patients without reflux in all segments (figure 3). In contrast, the median time from DVT to complete recanalization (lysis time) of all segments was about 9 to 12 months (more than 6 months) for DVT patients who developed reflux as the main determinant of symptomatic PTS (figure 6). As shown in figure 2, loss of valve competence leading to ambulatory venous hypertension (AVP) and diversion of venous flow through incompetent perforator veins appear to play an important role in the development of late complications of PTS. In the study of 123 legs with DVT (107 patients) by Markel et al about two third of the involved legs had developed valve incompetence (figure 7) 17 . The distribution of reflux at the end of the first year follow-up in this study was the following: popliteal vein, 58%, femoral vein, 37%, greater saphenous vein, 25% and posterior tibial vein, 18%. Reflux appeared to be more frequent in the segments previously affected by DVT (figure 7) 17 . The data of the DVT-LYSIS reflux studies in figures 3 and 4 will predict that discontinuation of anticoagulation at 3 months post-DVT in DVT patients with rapid recanalization of leg veins within 90 days (3 months, N=78 figure 6) will be followed by a very low DVT recurrence rate B). In patients with delayed recanalization at 6 to 12 months DVT discontinuation are at high risk for reflux and PTS development and therefore candidates for continuation of MECS and anticoagulation for at least 1 to 2 years. In the Maastricht study 18 , 125 consecutive DVT patients with confirmed proximal DVT (22% had a history of previous VTE) were followed for 2 years using the Vilalta clinical scores on four consecutive visits; 3, 6, 12, and 24 months post-DVT. After 6 months, patients with allowed to discontinue MECS therapy. If reflux was discontinue MECS therapy. Accordingly, MECS therapy was discontinued in 17% of patients at 6 months, in 48% at 12 months, and in 50% at 24 months. Reflux on CUS was present in 74 of 101 (73.3%) tested patients. Reflux alone was not determinative for the prediction of PTS. The cumulative incidence of PTS was 13.3% at 6 months, 17.0% at 12 months, and 21.1% at 24 months. Varicosis or venous insufficiency (present in 11% at baseline) was significantly associated with PTS; hazard ratio 3.2 (1.2-9.1). In this study patients with a low probability for developing PTS can be identified as early as 6 months post-DVT 19,20. Individualized shortened duration of MECS therapy in post-DVT patients with no or asymptomatic reflux on Vilalta clinical scores seems to be a safe management option. o Global Journal of DUS at 6 months post-DVT in unprovoked DVT and DVT recurrence rate after discontinuation of anticoagulation is not predictive for DVT recurrence.

In a post-hoc analysis in a selected large group of 452 patients with unprovoked DVT (table 7), Le Gal et al performed DUS at time point 6 months if the post-DVT patient had signs or symptoms at time point 5 to 7 months post-DVT when oral anticoagulation (OAT) was stopped19. In the study of Le Gal et al 184 of 452 (46%) had overt PTS with any hyperpigmentation (=CEAP >4), edema (CEAP >3) or redness in either leg (table 3).

Recanalizattion on DUS was complete in 220 and abnormal in 231 with minimal wall thickening in 11, partial thrombus resolution in 78 and minimal thrombus resolution (obstruction) in 23 and missing data in 67, but reflux was not measured. During follow-up off OAT 45 of 231 with abnormal CUS (19.5%) and 32 out of 220 patients (14.6%) with normal DUS (complete recanalization) had recurrent VTE (figure 8) 19 .

Table 7 : Baseline characteristic of 452 patients with unprovoked DVT at time point 6 months post-DVT at time of discontinuation of anticoagulation 19 . D-dimer abpve the upper limit of normal after discontinuation surely belong to the group of symptomatic post-DVT patients at high risk to develop PTS. In the prolong study, extended anticoagulationin post-DVT patients with increased D-dimer reduced the risk of DVT recurrence from 11% patient/years to less than 2% patient/years, whereas the incidence of DVT recurrence was still increased, 4.4% patient/years, in post-DVT patients with a normal D-dimer on month after discontinuation of regular anticoagulation 20 . This may implicate that DVT recurrence in those patients with either a normal or increased D-dimer very likely do occur in those with incomplete or complete RVT after 6 months. Reflux was not measured in this study.

As the extension of the PROLONG study Palareti performed the DULCIS (D-dimer and ultrasound in combination Italian Study) to establish the optimal duration of anticoagulation for VTE in 988 evaluable DVT patients with a first unprovoked DVT 21 . After at least 3 months of anticoagulation D-dimer was measured and DUS performed to measure residual venous thrombosis (RVT <4 mm) and followed according two main strategies. First, if the D-dimer level was below age and gender specific cut-off for each of the different D-dimer assay used, antiocoagulation was stopped and D-dimer levels were reassessed at 15, 30, 60 and 90 days. If at time of at least 6 months post-DVT the D-dimer remained below the cut-off, anticoagulation was definitely stopped and patients were followed up for 2 years. In 506 (51%) of the 988 analyzed patients all Ddimer were below the cut-off in the 3 months (90 days) after stopping anticoagulation. The incidence of VTE was 2.8%, distal DVT 1.1% and superficial venous thrombosis (SVT) in 2.3% patient/years. Second, if one of the D-dimer levels was above the cut-off in the period of 3 month (90 days) after discontinuation anticoagulation was resumed. This cohort 373 patients with increased D-dimer levels above the age and gender adjusted cut-off levels received oral anticoagulation for 2 years follow-up and only 4 VTE events (0.7% patient/years) were observed at the cost of 14 major bleedings (2.3% patients/years) 21 . In a third cohort 109 patients (11% patient/years) with at least one D-dimer measurement above cut-off, who refused oral anticoagulation treatment the incidence of major VTE was 8.8%, and distal DVT or SVT 2.3% patient/years.

9. VII.

10. DVT and PTS Bridging the Gap

In view of the proposed concept in figure 6, complete recanalization within 1 to 3 months and no reflux is predicted to be associated with no PTS obviating the need of anticoagulation and MECS at 6 months post-DVT. Delayed incomplete or complete recanalization at 6 to 12 months post-DVT is associated with a high risk of DVY recurrence as the cause of PTS and usually complicated by reflux due to valve should be anticoagulated for 2 years and are to be considered for extended or even life-long anticoagulation with VKA or NOAC 13 . As prevention of DVT recurrence as the best option to prevent the occurrence and progression of PTS. Michiels &Moosdorff started in 2012 a pilot study to test the feasibility of a multicenter prospective management and safety outcome study to further improve the proposed concept in figures 9 and 10 in the primary care setting. destruction, thereby indicating the need to extend anticoagulant treatment and wearing MECS. Patients with delayed but complete recanalization with reflux or without RVT but no PTS at 6 to 12 months post-DVT while wearing MECS are candidates for extended anticoagulation for about one year and to be reevaluated at time point one year post-DVT according to the PROLONG and DULCIS strategy (figures 9 and 10) 13,20,21

| Number | % |

| C Classification | Symptom |

| Clinical: C | |

| C0 asymptomatic | No visible varicose veins |

| months post-DVT up to 2 years post-DVT 13 | ||

| 5 Subjective symptoms: Identical to S of CEAP 7 Objective sign : | All belong to | |

| C of CEAP 15 | ||

| Heaviness of the foot/leg | Pretibial oedema | C3 |

| Pain in calf/thigh | Induration of the skin | C4 |

| Cramps in calf/thigh | Hyperpigmentation | C4 |

| Pruritus | New venous ectasia | C2 |

| Paraesthesia | Redness | |

| Pain during calf compression (post DVT) | ||

| Ulceration of the skin | C5, C6 | |

| sign or symptom is graded with as 1, 2, or 3. | ||

| (1 = mild, 2 = moderate, 3 = severe). Ulceration of the skin 4 points | ||

| The presence leg ulcer is a late complication of PTS consistent with severe CVI, CEAP 5, 6. | ||

| Definition of clinical post-t romb ic syndrome ccording to Prandoni (Villalta) | ||

| Absent: | score <5 | |

| Mild-to-moderate: | score between 5 and 10 and 10 to 15 respectively at 2 consecutive visits | |

| Severe: | score >15 at 2 consecutive occasions | |

| Source: Pesavento R, Prandoni P. Phlebology Digest 2007;20:4-8 | ||