1. I.

Introduction ater incursion into buildings and homes leads to an increased frequency of upper and lower respiratory disease and abnormal lung function in adults and children (1)(2)(3)(4)(5)(6)(7)(8)(9)(10)(11)(12). Spontaneous pulmonary hemorrhage in infants is rare. Known causes in children and adults include environmental tobacco smoke, infections, traumatic injury, e .g. intratracheal tube, cardiac and vascular processes, e.g. von Willebrand disease (13). Pulmonary hemosiderosis (PH) is the result of chronic and recurrent pulmonary bleeding with the occurrence of hemosiderin laden pulmonary macrophages. Pulmonary hemorrhage associated with water intrusion, Stachybotrys chartarum, Aspergillus, Penicillium and tobacco smoke in Cleveland, Ohio was reported (14)(15)(16). Additional cases of PH include a one month-old infant with no environmental tobacco smoke and the presence of Aspergillus/Penicillium spp, Memnoniella, Alternaria, Cladosporium, Chaetomium, Torula and Stachybotrys. Roridin L-2, Roridin E and Satratoxin H were identified in a sample from the bedroom closet ceiling (17); PH in a 40 day-old male infant exposed to Penicillium and Trichoderma species for 2 weeks followed by an acute exposure to tobacco smoke (18); and an infant with pulmonary hemorrhage (19). Finally, Stachybotrys chartarum was isolated from the lungs of a 7 year-old male who recovered from pulmonary hemorrhage (20).

Hemolysins are produced by a several species of mold isolated from the homes associated with pulmonary bleeding in the Cleveland homes (21,22). However, other mold contaminants probably have a role in illnesses associated with mold exposure in water damaged structures. For example, mycotoxins have been demonstrated in the air, dust and building materials contaminated with mold. These include, but not necessarily limited to sterigmatocystin, trichothecenes, aflatoxins, gliotoxin, chaetoglobosum A, Roquefortine C (12,(23)(24)(25)(26)(27)(28)(29)(30). In addition, trichothecenes have been identified in the sera of individuals exposed to Stachybotrys chartarum (31) while gliotoxin is present in the sera of patients and mice with invasive aspergillosis (32} Trichothecenes, aflatoxins and ochratoxins are present in biopsy and autopsy specimens obtained from mold exposed subjects (33). More recently, trichothecenes, ochratoxins and aflatoxins were reported in the urine, nasal secretions, sinus biopsies, umbilical cord and placenta from a famil y of five with illnesses associated with a mold w Jack Dwayne Thrasher ? , Dennis H Hooper ? & Jeff Taber ? nasal blood discharge. Pathology demonstrated ares of peribronchial inflammation, intra-alveolar, and numerous hemosiderin laden macrophage (hemosiderosis). Environmental evaluation of the home revealed Stachybotrys, Aspergillus/Penicillium, Cladosporium and Chaetomium in various rooms of the home. Mycotoxins detected in the home included Sterigmatocystin, 5 methoxy-sterigmatocystin Roquefortine C, Satratoxin G and H, Roridin E and L-2, isosatratoxin Fas well as other Stachybotrys secondary metabolites. Aspergillus versicolor was identified by PCR-DNA analysis in the lungs and brain of the deceased child. Aflatoxin was detected in his lungs, while monocyclic trichothecenes were identified in the lungs, liver and brain. The literature is briefly reviewed on the subject of fungi and their secondary metabolites present in water-damaged homes and buildings. infested water-damaged home (34). In addition, individuals exposed to mold in their water-damaged homes with chronic fatigue also have the same mycotoxins in their urine (35).

In this communication we report on a healthy family of 6 (nonsmokers) who developed multiple symptoms and health problems (e.g. nasal bleeding, sinusitis, asthma, RADS) following a prolonged exposure to several genera of mold in a water damaged home.

Most significantly, fraternal twins were hospitalized with pulmonary bleeding. The female survived but developed RADS. The male twin died from respiratory failure and pulmonary bleeding. Both had in utero and neonatal exposure to these molds and their mycotoxins, including Stachybotrys chartarum. Real time PCR detected Aspergillus versicolor DNA in the brain and lungs of the deceased infant, while an ELISA procedure detected aflatoxins and trichothecenes in the lungs, liver and brain in autopsy materials from the deceased infant. In addition, mycotoxins produced by Penicillium sp., Asp. versicolor and S. chartarum were detected in bulk and dust samples from the home by LC/MS/MS.

2. II.

3. Materials and Methods

4. a) Description of the Home

The 3 bedroom home was located in Visalia, California. Construction was wood framing, exterior stucco, dry wall interior, asphalt shingles, fireplace, wood sub flooring, crawl space, attic and central air condition. It consisted of the following occupied rooms: Living room with a corner fireplace, play room with a baby crib, infant's bedroom where the twins slept, den immediately adjacent to the infant's bedroom, master bedroom, add on office, kitchen and two bath rooms. Upon moving into the home it was noticed to be in disrepair. The carpet was wet, moldy and falling apart with a musty odor. There was discoloration of ceiling dry-wall indicative of water intrusion, and water damage to the flooring. Serum samples from the surviving members of the family were sent to Aerotech Laboratories (Currently EMLab P & K) to perform the Hypersensitivity Pneumonitis Panel and for the detection of IgE, IgA and IgM antibodies against various molds. Antibodies against aflatoxin, trichothecenes and satratoxin adduct and Stachybotrys chartarum in sera of the family were tested by Immunosciences as previously reported (36). f) Real Time PCR (RT-QPCR) Mold DNA Analysis

The DNA probes for mold species utilized in the RT-QPCR included species of Aspergillus, Penicillium and Stachybotrys chartarum were developed and patented by Real Time Laboratories, Carrollton. Texas. The RT-QPCR was carried out as published (37). The tissues used for mold DNA and mycotoxins were emulsified and extracted as described (33)(34)(35) are briefly reviewed below. g) Detection of Mycotoxins in Autopsy Specimens by an ELISA Procedure 25 mg of the lung, liver and brain were received frozen or embedded in paraffin blocks. They were analyzed for aflatoxins (AT), trichothecenes (MT) and ochratoxin A (OTA) using immune affinity columns , and T-2 and HT-2 Ochra Test ,(Afla Test® test kits, VICAM, L.P., Watertown, MA) containing specific monoclonal antibodies. The tissues were emulsified in phosphate buffered saline (PBS, 0.9%) and reagent grade methanol (Sigma-Aldrich).in a 1:1 dilution. To disrupt the cells, tissues were bead beated using silica beads (Sigma-Aldrich) for 1 minute at the speed of 45 rpm, heated at 65 0 C for 15 minutes. Samples were centrifuged at 13000 rpm for 2 minutes. 500 ?l of cellular extract was placed in a glass tube, and further diluted in PBS prior to testing. All samples were free of paraffin (33)(34)(35).

Samples were then applied to an Afla Test® column (VICAM, L.P., Watertown, MA) which contains specific monoclonal antibodies (MT) directed against AT (B1, B2, G1, and G2), OTA) and monocyclic tricho the cenes. Columns were washed twice with reagent grade water (Fisher Health Care, Houston, Texas). The samples were eluted from the column to remove the bound mycotoxins with reagent grade methanol. Fluorochrome developer (AFLATEST ® Developer, VICAM) was added to the extracted methanol. All samples were read by fluorometry (Sequoia-Turner Fluorometer, Model 450, which was calibrated using standards supplied by VICAM (Green Filter = 2, and Red Filter = 120). Spiked standards using known amounts of AT B1, B2, G1, and G2 (Trilogy Analytical Laboratory Inc., Washington, Missouri) of human heart tissue were run as validation controls prior to testing (sensitivity of 95% and specificity of 92%). Known controls of mycotoxins (50 ppb, 25 ppb, and 1.25 ppb, Trilogy Analytical Laboratory and Real Time Laboratories, Carrollton, Texas) were run with each test. The eluted solution was then read by fluorometry at 450 Angstroms. The lower and upper limits of detection are III.

5. Results

6. a) Family Health

The two adults, nonsmokers, and two older male children were healthy prior to moving into the mold contaminated home. They resided in the home until November/December 2002. The home was razed in early 2002. Within two months of occupancy all members began to experience symptoms and health problems that are summarized in Tables 1 and 2. All surviving members developed lung disease and were positive when tested for Hypersensitivity pneumonitis ( Table 2) and were given the diagnosis of RADS/asthma with prescribed bronchodilators.

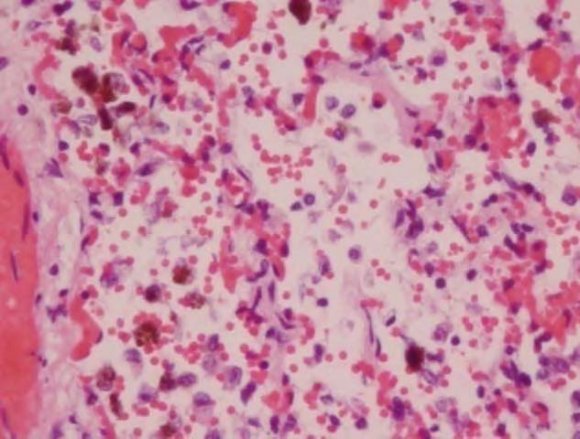

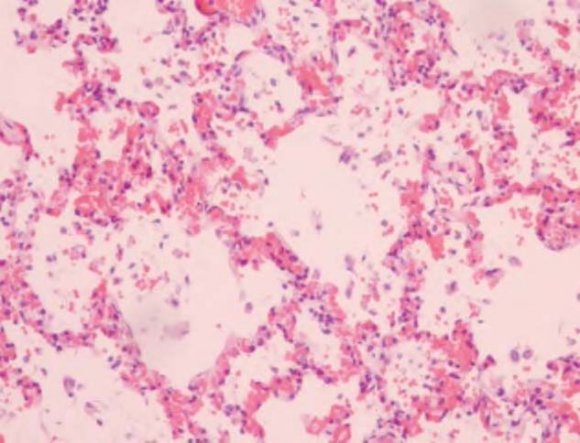

In addition, all members of the family had reduced RBC hemoglobin (Hb) and were diagnosed as anemic. Nose bleeds and a flu-like illness were other common symptoms (Table 1). After moving out of the contaminated home, their health improved, however, they remained symptomatic with the RADS/asthma as well as other symptoms such as fatigue and generally not feeling as well as they did prior to occupation. There was no family history of von Willebrand disease. The following abnormalities were listed in the final autopsy report: (1) liver had mold congestion; (2) Heart had mild hypertrophy without inflammation; (3) Lungs had marked vascular congestion, foci peribronchial inflammation, intra-alveolar blood numerous aggregates of pigment laden macrophages (hemosiderosis) (Figure 1). All other organs were normal in appearance.. The cause of death was listed as respiratory failure with pulmonary bleeding and hemosiderosis.

7. 2.

3. 4.

8. 5.

The female twin had nasal bleeding, fever, deceased RBC hemoglobin (anemia) coughing and difficulty breathing. She was hospitalized once and released after being stabilized. The male sibling upon arriving home put in following birth birth he had ER visits, frequent physician visits and was in hospital for severe respiratory problems. At home he was found face down in his crib motionless, blue and with blood coming from the nose and mouth. He was pronounced dead upon arrival at the hospital.

9. B. Autopsy Slides of Lung (H & E) d) Hypersensitivity Pneumonitis and Antibodies to Mycotoxins

The father, mother, two boys and the surviving twin were positive with respect to the Hypersensitivity pneumonitis panel (Table 2). The father had positive IgG antibodies to the four molds (M. Faeni, A pullulans, A. alternata and A. fumigatus) followed by the mother (M. faeni and A. pullulans) and the three children (M. Faeni).

All experienced symptoms of shortness of breath (SOB), RADS and/or asthma requiring bronchodilators.

10. Antibodies against Stachybotrys chartarum

were positive in each family member as follows: Father (IgA and IgG); Mother (IgA); two sons (IgG) and twin daughter (IgG). The data on titers are not shown.

Antibodies to albumin adducts of AT, trichothecenes (MT) and satratoxin (ST) were positive as follows: ( 1

11. f) Mycotoxin Identification in the Home

The results for the detection of mycotoxins in bulk samples are presented in Table 4. The results are designated as present (at or above detection limit) or not present (not detected). Sterigmatocystin and 5methoxysterigmatocystin were detected in three rooms, the air conditioning duct and AC filter. Sterigmatocystin was at or above the reporting limit of 20 ng. Chaetoglobo sum A, B, and C were not identified. Real-Time PCR analysis detected Aspergillus versicolor in the frozen and paraffin embedded tissues as follows: Lung (1056 spores/g; Liver (0) and brain (7 spores/gram) Table 5).

Ascospores and Basidiospores were also present in some rooms of the home. Torula was detected in Addition room W. wall sample. Air spore counts total 1,577 to2, 222sporex/m 3 . Stachybotrys and Chaetomium were not detected in the outdoor air samples. Stachybotrys was detected in air of the children's play room. .Stachybotrys and Chaetomium spores were detected in the carpeting.

Roquefortine C was detected in two rooms, The most commonly detected mycotoxins were the trichothecenes: Satratoxin H (detection limit of 7.0 ng), Isosatratoxin F, Satratoxin G, Roridin L-2, Isororidin E, and Roridin E. In addition, the Stachybotrys metabolites 6B-Hydroxydolaabella MER-5003 Mol. Wt. 47 and Mol. Wt 412 were also present. Standards were not available for several of the mycotoxins (**).

12. Discussion

The initial literature regarding pulmonary hemorrhaging in infants and mold was limited to the identification of molds, including S. chartarum, in the homes of the affected infants. As a result, we have held on to the data presented herein until sufficient information became available in the literature to discuss the health affects observed in this family.

The question is what is the mode of exposure to antigens and toxins in these environments? Bench experiments and results from indoor testing of water damaged homes offer some insight. Bench testing has demonstrated that colonies of mold and bacteria shed particulates (fungal fragments) less than the size of spores in the range of 0.03 to 0.3 microns. The question is what is the mode of exposure to antigens and toxins in these environments? Bench experiments and results even much greater than original estimates of 500 times the spore count (40,41). The aerodynamic characteristics of the fungal fragments apparently have a respiratory deposition 230 -250 greater than spores. has demonstrated that the mechanisms involved in this release includes colony structure, moisture conditions, air velocities and vibration (38)(39)(40)(41). The fragments contain antigens, mycotoxins, glucans, endotoxins, exotoxins and a variety of digestive proteins and hemolysins (21,22,38,40,42,43).The ratio of fungal fragments to spores (F/S) in the indoor in moldy houses has been calculated. The F/S for fragment sizes of 0.03 to 0.3 would be between10 3 to 10 6 . These results indicate that the actual contribution of the fungal fragments to the overall exposure may be very high, With respect to infants, the lower airway deposition is 4-5 times greater than that for adults (41).

13. Global

The family lived for 8 years in the water damaged home with musty odors and visible mold that resulted from faulty roofing. Inspection and testing of the home led to the identification of elevated Aspergillus/Penicillium spp, Chaetomium, Stachybotrys chartarum among other genera in bulk samples taken from several areas of the home. S. chartarum was present in samples taken from the fraternal twins play room (family den) as well as living room (addition walls) (Table 3). The condition of the home was sufficiently serious that the Fresno County Department of Health required the family to move out. The home was eventually razed because of mold contamination and construction defects.

The parents and two older children experienced a chronic flu-like condition with multiple symptoms as summarized in Table 1. These included nasal congestion and bleeding, sinusitis, headaches, fatigue, decreased ability to concentrate and respiratory difficulties diagnosed as RADS/asthma condition requiring bronchodilators. In addition, they had positive antibodies to the hypersensitivity pneumonitis panel (Table 2). It is well recognized that respiratory disease and infections occur in occupants of buildings and homes with water-damage and the presence of mold, bacteria and their secondary metabolites (1)(2)(3)(4)(5)(6)(7)(8)(9)(10)(11)(12). The fungi associated with respiratory disease include the genera of Alternaria, Aspergillus, Cladosporium and Penicillium (1-12, 44, 45).

The entire family had episodes of nose bleeds. However, the conditions of the twins were more serious leading to hospital stays. It is noteworthy that Stachylysin has been detected in the sera of mice, humans and indoor environment of water damaged homes and buildings (46). In addition, several species of Aspergillus and Penicillium are known to produce hemolysins and probably siderophores (21,22,(47)(48)(49). Thus, both nasal and pulmonary bleeding may well have been the result of multiple mold hemolysins as well as infection from mold and bacteria. The female twin recovered sufficiently but developed RADS. The fraternal brother was found dead in his crib with bleeding from his nose and mouth. The autopsy revealed pulmonary bleeding and hemosiderosis (Fig. 1).

PCR-DNA demonstrated Aspergillus versicolor in his lungs, which produces Versilysin (21,22). In addition, AT (lungs) and MT (lungs, liver, and brain) were present in the autopsy samples. The observations on the deceased twin, as well as the other members of the family, point towards the recognition of fungi and their secondary on the health of the occupants. The presence of multiple biocontaminants, their complexity of damp indoor spaces as well as microbial particulates ranging from 0.03 to 0.3 microns probably have an impact upon human health that should be taken into account (31,34,35,(38)(39)(40)(41)(42). Finally, it is becoming increasingly apparent that occupants of water damaged environments have mycotoxins in their serum, urine, nasal cavity and various tissues (31,(33)(34)(35). In conclusion, indoor molds resulting from water-intrusion do produce and release fungal fragments (0.03-0.3 microns), multiple species of mold and bacteria, secondary metabolites, nano-particulates and other biocontaminants that most likely impinge upon the health of occupants (23)(24)(25)(26)(27)(28)(29)(30)(31)(38)(39)(40)(41)(42)(43).

The younger of the two older sons was diagnosed with developmental delay (autistic spectrum disorder) at age 6. Since this child was in the home from infancy the exposure to microbial secondary metabolites in the home may have contributed to this condition. Information in the literature on autistic spectrum disorders suggests that mold and mycotoxin exposure appear to be contributing factors in this neurological disorder (50)(51)(52)(53). If the respiratory deposition of fungal fragments that contain mycotoxins is considered, this is a plausible explanation for his neurological condition. A model of the human nasal-sinus cavity has shown that flow patterns in the ethmoid-sphenoid-olfactory area will allow the deposition of nanoparticles into these structures (54). Furthermore, the instillation of trichothecene mycotoxins into the nasal cavities of rodents and Rhesus monkeys causes rhinitis, nasal inflammation, apoptosis of the olfactory sensory neurons, the olfactory bulb and spreads to the brain of rodents (55)(56)(57)(58). Furthermore, fine and ultrafine particulates with attached toxins are translocated to systemic circulation by crossing the alveolar membranes and into the brain via the olfactory tract as well as oxidative stress, systemic inflammation associated in cognitive decline. (59 -62) . Comments are in order regarding the role or secondary exposure to cigarette smoke. The CDC pointed out that the Cleveland infants had exposure to tobacco smoke in their homes as verified by Dearborn et al (13,15). The family in this investigation consisted of nonsmokers, but experienced nasal bleeding and the death of one infant from pulmonary hemorrhage. Although, secondary tobacco smoke contains LC/MS/MS detection of mycotoxins demonstrated the presence of S. chartarum trichothecenes in bulk samples from areas of the home, including the twin's playroom. Additionally, sterigmatocystin, 5methoxysterigmatocystin and roquefortine C were also detected in the home and the HVAC system (Table 4). These observations add to the increasing evidence that mycotoxins are present in water-damaged buildings and homes. As such they represent a toxic source of exposure via inhalation as well as oral and skin exposure (12, 17, 23-30, 33-35, 42). bacteria, fungi and their toxins present in the environmental cigarette smoke in the Cleveland cases should also be considered. However, the members of the family presented herein were expose molds and mycotoxins present in a water-damage home. In addition, Aspergillus versicolor DNA and aflatoxins and trichothecenes were detected in the lungs and brain of the deceased infant.

14. V. Conclusion

The parents and children in this case study were non-smokers. They were exposed to high concentrations of mold spores and mycotoxins present in the indoor environment of their rented home. The parents and siblings experienced multiple health conditions associated with the exposure. With respect to the fraternal twins, the sister developed nasal bleeding, fever, anemia and difficulty with breathing. She recovered sufficiently after being in the hospital and returned home. The male twin died from pulmonary bleeding and failure. PCR-DNA testing revealed Aspergillus versicolor in the lungs, liver and brain. Tests for mycotoxins detected aflatoxin lungs and trichothecenes in the lungs, liver and brain. Thus, exposure to molds and their secondary metabolites present in a water-damaged indoor environment presents a health hazard to the occupants.

| c) Environmental Myco toxin Testing |

| Bulk and wipe samples were taken from various |

| areas of the home and sent under chain of custody to P- |

| K Jarvis (currently Bureau Veritas North America), Novi, |

| Michigan to test for a variety of mycotoxins produced by |

| Aspergillus and Penicillium spp. and Stachybotrys |

| chartarum. The samples were extracted with methanol, |

| run on LC/MS/MS and analyzed by John Neville, Ph.D. |

| d) Autopsy of the Deceased Child |

| An autopsy was performed by G. Walter, MD, |

| Coroner's Office, Tulare County, California. A second |

| opinion regarding the results of the autopsy and |

| histopathology was done by a pediatric pathologist D. |

| Scharnhorst, M.D., Ph. D, Valley Children's Hospital, |

| Madera, California. Histology slides were only stained |

| with Hematoxylin Eosin. Paraffin embedded and frozen |

| samples of liver, lung and brain of deceased infant were |

| sent to RealTime Laboratories, Carrollton, Texas to test |

| for mycotoxins and the presence of mold DNA. |

| e) Hypersensitivity Pneumonitis and Mycotoxin |

| Antibodies: |

| California. The following defects were noted: (1) faulty |

| roofing; (2) increased moisture readings from 30 to 100 |

| %; (3) Ceiling water stains throughout the house; (4) |

| Visual mold growth; and (5) improperly installed |

| shingles which allowed moisture intrusion under the |

| shingles and into the interior of home, e.g attic and wall |

| cavities. The home was eventually razed because of the |

| disrepair, water damage and mold growth. |

| b) Mold Testing (Air, swab and Bulk Sampling |

| Visual inspections, bioaerosols, bulk and wipe |

| sampling of the home were done under the direction of |

| Jeff Taber, Kings County Public Health Department. |

| Bulk, wipe and air bioaerosols were sent under chain of |

| custody to Aerotech Laboratories (Currently EM Lab P & |

| Family Member | Health and Symptoms |

| anemia) | |

| and increased neutrophils. Negative allergy skin testing. Abnormal | |

| PFT RADS. Albuterol. | |

| Son, age 10 (Son 1) | Normal well baby Exam. Flu-like symptoms, skin rash, frequent |

| colds, sore throat, fevers, coughing, shortness of breath, vomiting, | |

| gastroenteritis, conjunctivitis RADs/asthma, Albuterol | |

| Youngest Son, age 8 (son 2) | Normal well baby exam. Flu-like illness, developmental delay, |

| bilateral OTM, conjunctivitis, chest congestion, sinusitis, headaches. | |

| At age 4 diagnosed with developmental delay, delayed speech and | |

| language, and at age 6 with autistic spectrum disorder. RADS | |

| requiring Albuterol. | |

| Fraternal Twin (female) 18 moths | Normal well baby exam. Symptoms began at approximate 3 months |

| of age: fever, congestion, coughing, hoarseness, shortness of |

| Organism | Mother 1 | Father 2 | Son (1)) 3 | Son (2) 4 | Female Twin 2 |

| M. faeni | + | + | + | + | + |

| A. pullulans | + | + | - | - | - |

| A. Alternata | - | + | - | - | - |

| A. fumigatus | - | + | - | - | - |

| Volume Issue V Version I |

| The tests were performed by Jon Neville, PK-Jarvis, Novi, MI | |||||||||

| Mycotoxin | Livin | Room | Room | NW | Living | Room | Room | Room | Reportin |

| g | Additi | Additio | Bdr | Room | Additio | Addition | Addition | g | |

| Roo | on | n | m | Floor | n | S. Wall | N. wall | Limit in | |

| m | W. | Middle | Clos | at | SW | ng | |||

| N. | Wall | et | Firepla | Wall | |||||

| Wall | ce | ||||||||

| Sterigmatocystin | -- | Present | -- | -- | -- | Present | Present | -- | 20 |

| 5- | -- | Present | -- | -- | -- | Present | Present | -- | ** |

| methoxysterimatocystin | |||||||||

| Chaetoglobosum A | -- | NP | NP | NP | -- | NP | NP | NP | ** |

| Chaetoglobosum B | -- | NP | NP | NP | -- | NP | NP | NP | ** |

| Chaetoglobosum C | -- | NP | NP | NP | -- | NP | NP | NP | ** |

| Griseofulvin | -- | NP | -- | -- | -- | NP | NP | -- | 10 |

| Roquefortine C | -- | Present | -- | -- | -- | Present | NP | -- | 0.4 |

| Satratoxin H | NP | Present Present | NP | NP | Present | Present | Present | 7.0 | |

| Trichodermol | NP | NP | NP | NP | NP | NP | NP | NP | ** |

| Trichodermin | NP | NP | NP | NP | NP | NP | NP | NP | ** |

| Isosatratoxin F | NP | Present | NP | NP | NP | Present | Present | Present | ** |

| Satratoxin G | NP | Present | NP | NP | NP | Present | Present | Present | ** |

| Roridin L-2 | NP | Present | NP | NP | NP | Present | Present | Present | ** |

| Isororidin E | NP | Present | NP | NP | NP | Present | Present | Present | ** |

| Roridin E | NP | Present | NP | NP | NP | Present | Present | Present | ** |

| Epoxydolabellane A | NP | NP | NP | NP | NP | NP | NP | NP | ** |

| 6B-Hydroxydolaabella | Prese | Present Present | NP | Present Present | Present | Present | ** | ||

| nt | |||||||||

| MER-5003 M. Wt. 470 | Prese | Present Present | NP | Present Present | Present | Present | ** | ||

| nt | |||||||||

| MER-5003 W. Wt. 412 | Prese | Present Present | NP | Present Present | Present | Present | ** | ||

| nt | |||||||||

| Abbreviations: ** (standards not available; --(not tested); NP (not present) | |||||||||

| Sample | Species | Spores/g |

| Aspergillus versicolor | Paraffin embedded | |

| tissue | ||

| Lung | Present | 1066 |

| Liver | Absent | 0 |

| Brain | Present | 7 |

| h) Mycotoxins Detected in the Deceased Tissues | ||